Named Virtues

The 51st in the Egan Pattern Language

A note: this pattern gets into some spicy territory! As I’ll explain below, so far as I know the views here are not directly found in Kieran Egan’s work, but do flow from it.

1. A problem

He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.

–Frederick Nietzsche

True education demands a lot of students and teachers. Moving into the unknown, taking on hard tasks, putting your own beliefs up to be challenged — Egan is right when he says that education is a true adventure, and adventure means risks.

To endure this, students and teachers need deep, shared values.

The hitch, for most schools, is that shared values are hard. Public schools are responsible to the public: they can’t dictate values, but can only reflect whatever values held by the lump average of local citizens. Private schools are responsible to whichever families they’ve already accepted. This handcuffs how much energy they’re able to generate to face the pains of real education.1

2. Basic plan

At their inception, schools (and other educational communities) should choose, among the many potential human values, the handful that will define them. Then they should be zealous about pursuing those. Sacrifice sensible things to uphold them. Find ways for these virtues to strengthen the culture of classrooms and infiltrate the content of the curriculum itself.

3. What you might see

Kids being held to high standards — along with teachers, administrators, and janitorial staff.

Stories from history and literature being particular chosen to explore what the virtues of the school can look like.

Critical examinations of the values of the school — including openly questioning them.

4. Why?

When a group shares values, hard things become easy…

…and there are few things harder than education.

Humans rule the world not because we’re individually so clever (though that helps), but because we’re able to become a superorganism — we transcend our boundaries and become a new kind of creature. As Jonathan Haidt quipped in The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion:

we’re 90% ape and 10% bee.

Or as Joseph Henrich wrote in The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter:

the wrong way to understand humans is to think that we are just a really smart, though somewhat less hairy, chimpanzee…. Our species’ dependence on cumulative culture for survival… mean[s] that humans… are literally the beginnings of a new kind of animal.

But you can’t make much use of this without shared values.

5. Egan’s insight An insight that’s sort of implied by Egan?

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Every culture has its own bespoke blend of values that it sacrifices to inculcate among the next generation. And this makes sense: cultures that don’t have this fall apart — indeed, these strong values are part of what we mean by “culture”.

Every group anthropologists have described uses stories to express the most important convictions of the group. In the ancestral past, cultures that didn’t standardize values starved or were massacred; in the modern day, they beshiver into subcultures.2

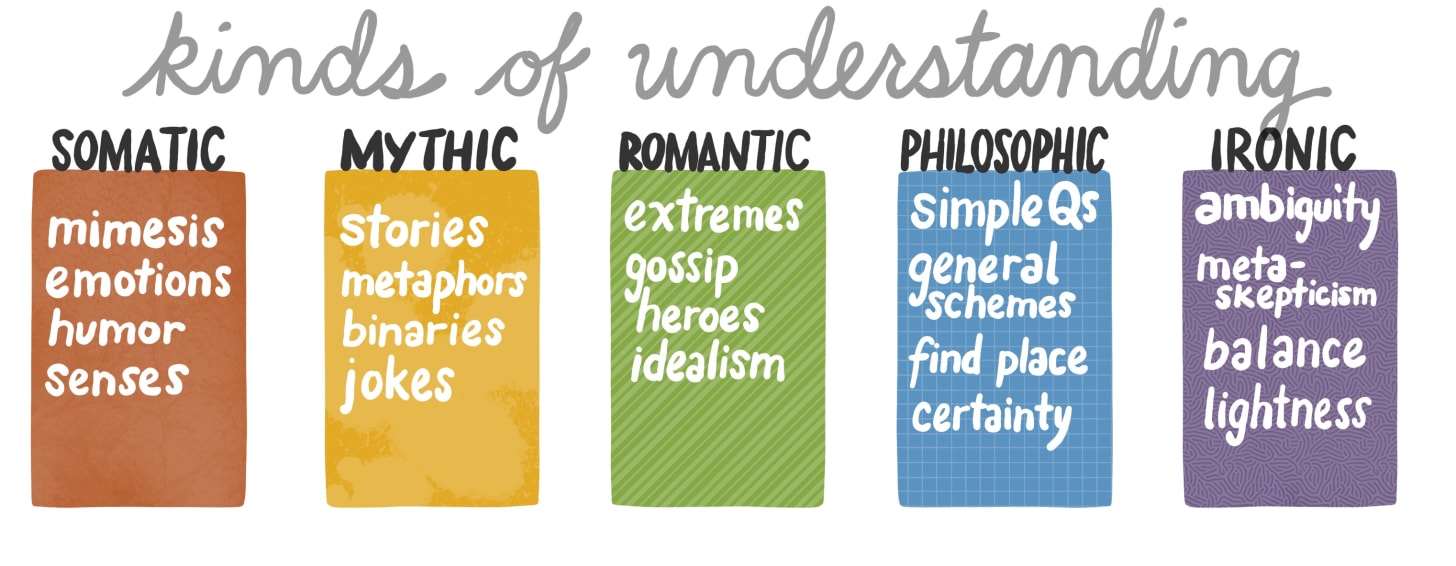

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Powerfully, because values can supercharge the whole curriculum.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you know that 🧙♂️STORIES are the engines of human development. But what gives stories their power? In fact, what gives any of the tools (🤸♀️SENSES, 🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGES, 🧙♂️BINARY OPPOSITES…) their power? I think the answer is values.

Some of those values, of course, come from evolution: every animal feels strongly about being eaten, burned, or dissolved in acid. But those evolutionary values get extended by the cultures we grow up in, and become virtues that, sometimes, people are even willing to stake their lives on.

I worry that when I say “stories are near the center of a good education” what most people hear is “education should be light and fun!” Unfortunately, I mean quite the opposite: education should matter, should be weighty. And what matters in a story isn’t the external stuff (the characters, the plot, and so on), but the values it conveys.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Oh, like morals? I love a story with a good, clear, moral at the end of it!

Holy God no that is not what we’re talking about.

Explicit morals usually ruin stories. They squeeze all a story’s values into a tiny, lackluster sentence. They shortcut contemplation and discussion. Stories that end with with “morals” should not be used in Egan education.3

But all good stories are thick with values. They’re what make us care. They’re what give stories their humanity.

I.I.: Can you give an example?

Take Ghostbusters, which is precisely no one’s idea of a preachy movie. It’s chockablock in virtue:

it’s better to be a scrappy entrepreneur than to work in academia

ghosts are bad

governmental red tape may kill us all

gritty cities are beautiful4

I.I.: If all stories have virtues, then “shared virtues” seems easy.

The difficulty is in the “shared” part. Note that each of those virtues in Ghostbusters are controversial: many people prefer the academy to entrepreneurship, the EPA to unregulated technology, and a clean, crime-free suburb to 1980’s New York.

To make any value central will necessarily turns some people away. There’s no way around this.

I.I.: And why would I want to turn people away from my school? What’s your proposed payoff of this?

I said before that shared values allow for people to work hard together, but another payoff is that shared values can supercharge the whole curriculum, making everything matter to kids (and teachers) more.

For example, say one of your values is “beauty”. Teachers then should ask what beauty can be found in the water cycle, and how beauty can be experienced in balancing equations. How can we bring beauty into middle school geography? Where’s the beauty in the quadratic formula — or is it ugly? In literature, you can have searching discussions about why traditional fairy tales equate beauty with goodness and ugliness with evil. Soon, you can begin to discuss whether there is such thing as beauty, or whether it’s an oppressive creation of evolution/capitalism/the patriarchy/whatever.

All of these things can take you deeper into the content of the curriculum, but they can only come when values are shared.

6. This might be especially useful for…

The goodie-goodie Boy Scout who gets a warm glow from having something to believe in, and the eye-rolling cynic who thinks values are only for normies.

7. Critical questions

Q: Are you saying that schools should become CULTS? (Nobody here except me and you, please speak freely!)

That word is dangerous, because people commonly use it in two quite different ways:

a group with weird beliefs that demands loyalty and shapes people’s behavior in unusual ways (e.g. “the Heaven’s Gate cult” or “the cult of Charles Manson”)

a passionate community of people deeply committed to a shared way of life that creates strong bonds and gives members identity and purpose (e.g. “the cult of Apple” and “the cult of Trader Joe’s”)

Obviously, those are related! I’ll avoid using the “c-word”, and instead point to a different part of culture:

Schools should run themselves as start-ups.

Startups are hard. More than half are dead by their third birthday. People who have reflected on why a few actually thrive — I’m thinking of writers like Paul Graham, Reid Hoffman, Ben Horowitz, and Sam Altman — beat the drum of “value alignment”, “cultural DNA”, “mission-driven identity”, and many other synonyms for The Word Which Cannot Be Named.

So we’ll go with “startup culture” instead.

Q: Whatever terms you choose, you’re playing with fire. How can you avoid the truly disastrous aspects of cults?

Egan would say: IRONIC (😏) understanding.

That’s to say: an Egan education calls you to take beliefs extraordinarily seriously, but also to sniff out the limits of those beliefs.

I’ve talking with Alessandro as to whether Egan education would be a bad fit for any particular kind school. His answer: fundamentalist ones. And by “fundamentalist”, he emphasized, he doesn’t just mean religious schools, but also ideological secular ones. (In fact, many religious traditions contain safeguards against fundamentalism — the best Protestant thinkers evince delightful irony, and the Jesuits are as anti-fundamentalist as you’ll find.)

Q: You’re treating this as unusual, but don’t, like, all middle and high schools have a statement of values, or whatever? I seem to remember words like “honesty” or “bravery” being on the student manual I was given the first day of sixth grade.

Did you look for examples in history, or explore their perils in literature? Were you ever called out for not living up to them? Would you and your friends have been able to yell them in unison at a moment’s notice? Did you change your actions at all to fit them?

That most of us can’t remember what those values actually were is telling. What those are is a slapped-on facsimile of what we’re talking about.

Q: Why only choose a few?

You can’t “focus” on everything.

Say, for example, a school tried to pursue all the 24 values catalogued by social scientists Christopher Peterson and Marty Seligman in their cross-cultural survey:

Wisdom: creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, and perspective

Courage: bravery, persistence, integrity, and vitality

Humanity: love, kindness, and social intelligence

Justice: citizenship, fairness, and leadership

Temperance: forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation

Transcendence: appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, and spirituality.

Twenty-four is too much; they overload the brain. Even the six categories they chunked those into are too much to “focus” on. No strong culture can emphasize each of those equally.

Q: You say schools should “sacrifice sensible things” to uphold these virtues. Isn’t that a bit extreme?

If something’s a “value”, that means you’d be willing to trade it for other things. And ostentatious sacrifices are an important way to show what you value.

For example, if a school really values equality, then the head of school should probably get a specially-assigned parking spot… at the far end of the lot. If they really value honesty, then a popular teacher who casually lies should face a public reprimand.

Q: How should these virtues be brought into schools?

The way that cultures inculcate virtues is precisely through the tools that Egan begs us to make use of anyway.

Just as a few examples: 🧙♂️STORIES run on 🧙♂️BINARIES, and many binaries are of virtues: cowardice/bravery, dishonesty/integrity, cruelty/kindness, bias/fairness… 🦹♂️HEROES explore the many forms a virtue can take, and the cost of following them. 👩🔬FINICKY DEFINITIONS help us get clear as to what these values actually mean, and 👩🔬BATTLING IDEAS help us think through which are really most important. 😏AMBIGUITY helps us realize that the virtues that can be named are not the real virtues — that robotically following a list is a terrible way to live.

Q: You’re talking as if we’re setting up new schools — but what if we’re reforming existing schools?

Organizational transformation is hard, and I don’t pretend that I know anything about doing it. Maybe this is too hard for schools that already exist. (If you have experience in this and aren’t a paid subscriber, let me know, and I’ll gift you a week’s paid subscription so you can tell us about it in the comments.)

Q: Lay it out simply: why do we need this weird, dangerous thing?

[Sigh]… Because it’s the human norm.

It’s common for people to look back fondly on tight-knit hunter-gatherer tribal life. If only we could bring in soap and antibiotics, they often say, I’d go there in a heartbeat.

What’s under-appreciated is that tribal life is held together by fervently shared values, specifically ones that surrounding groups find “weird”. (One thinks of kosher and halal laws. Any tribal group plopped into contemporary society would be identified as a “cult” in a heartbeat.) The original human recipe for flourishing seems to require something like this.

Q: “Virtue” sounds right-coded. Is this secretly a conservative pattern?

No.

Eons ago, back in another political dispensation, the conservative Right grabbed the word “virtue” — see the bestselling The Book of Virtues, written by William Bennett, Ronald Regan’s Secretary of Education — and the Left treated it as radioactive. Happily, that seems to be changing.

More importantly, though, the conception of virtue has never been the sole province of any philosophy. Progressives obviously have exceptionally strong virtues! Sometimes they’re different (see, again, Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind), and sometimes they’re just pointed toward different ends.

Q: I’m a homeschooler. What does this have to do with me?

Much. See the Afterword.

This is a touchy subject! (There’s a reason I’ve taken NEARLY A YEAR to write this.) I’m going to limit the comments to folks with a little skin in the game — paid subscribers. Become one and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

Once you decide on your values, they should be posted around the building, so that everyone who visits your school should walk away with them ringing in their memory.

9. Who else is doing this?

There are schools around the world who know who they are.

International Baccalaureate schools worldwide share a learner profile that describes “a broad range of human capacities and responsibilities that go beyond academic success.” Their list includes “inquirers”, “knowledgeable”, and “reflective”.

Jesuit schools have a “profile of a graduate at graduation” that includes “open to growth”, “religious”, and “loving and committed to doing justice”.

The KIPP charter schools focus on seven of the Peterson/Seligman virtues: “zest”, “grit”, “optimism”, “self-control”, “gratitude”, “social intelligence”, and “curiosity”.

The Round Square Schools have their six IDEALS: Internationalism, Democracy, Environment, Adventure, Leadership, and Service.

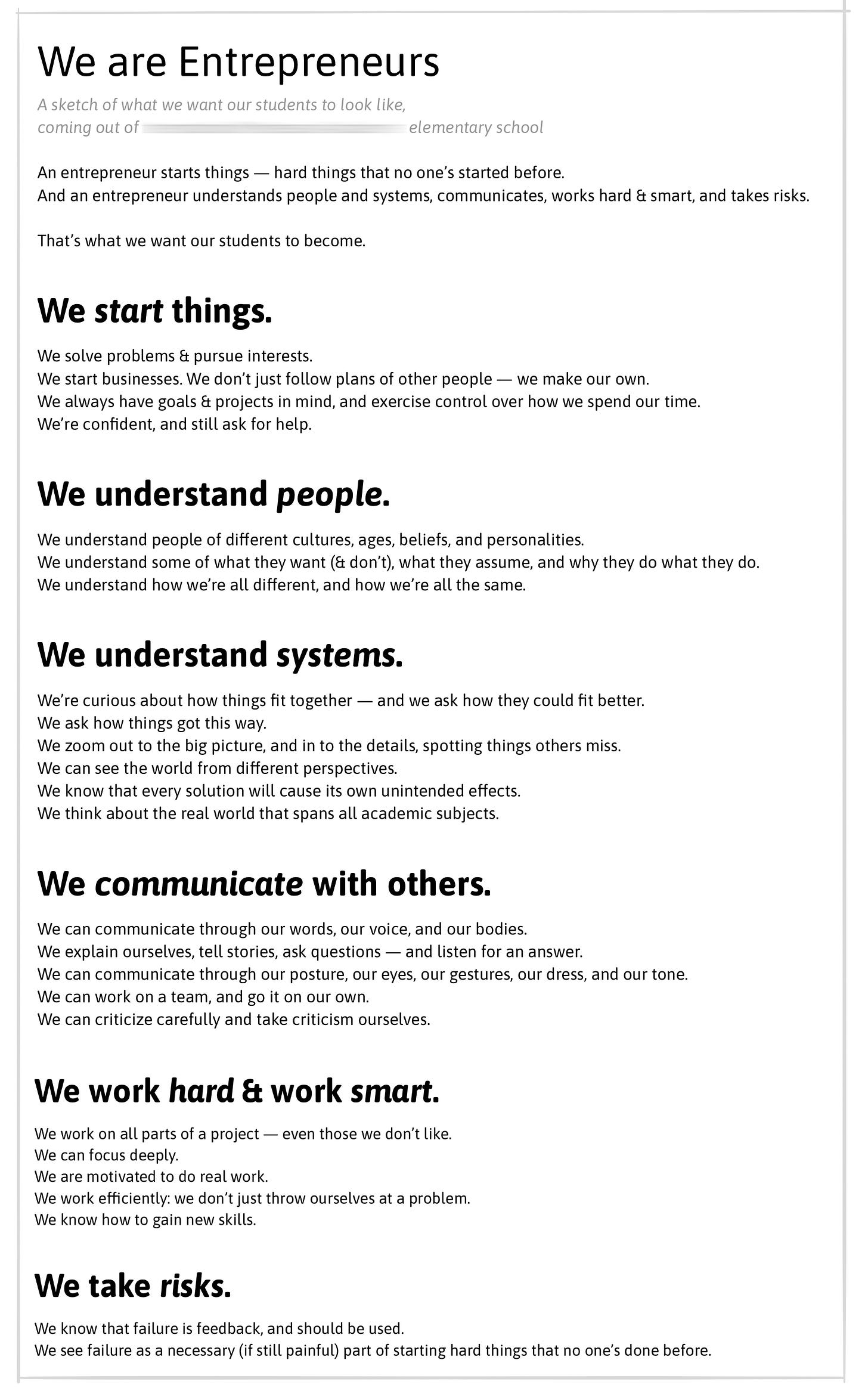

And when my wife and I helped run a start-up elementary school outside Seattle, we chose six. As the stated goal of the school was to promote entrepreneurship, we picked them to support that:

How might we start small, now?

Read. Michael. Strong.

Michael’s the undisputed champion of making schools into tight communities that matter to kids. He’s the co-author (with a founder of Whole Foods) of Be the Solution: How Entrepreneurs and Conscious Capitalists Can Solve All the World’s Problems. He conducted years of Socratic conversations with a young girl named Alana who went to attend Harvard’s celebrated Introduction to Computer Science at the age of 12 (you can watch them on YouTube).

Michael is, somehow, more bullish on schools being tribes than I am. If this is interesting to you, I suggest you start with three specific posts:

in “What Are We Building? The Case for New Subcultures”, he argues that mainstream culture is failing us, and demands we build “radical new subcultures” where committed members push moral and personal growth beyond the stale norms of society

in “The Missing Institution: Why Are Young People Not Flourishing?” he argues that no existing system truly invests in youth’s moral and spiritual development, and calls for a completely new institution devoted to fostering deeper purpose

in “Why Focus on the Importance of Subculture Creation? We Are Shaped by the Norms and Ideals of Those Around Us” he shows how schools can become intentional communities built around a specific recipe for human flourishing

10. Related patterns

Virtues can be explored through Epic Stories°, where they can become fuel for Philosophy Everywhere° and Intergenerational Conversation°. They can become complicated by the heroes displayed on the Wall of Saints°.

And this is going to be the foundation for Every School a Tribe° and Youth Charters°, which are going to leverage shared values into sharing skills to give kids the best opportunities possible.

Afterword:

Q: Is there a homeschooling version of this?

Yes, and it’s coming soon.

I mentioned the Skeleton Army above. (For new readers, that’s the group of 60 homeschooling families around the world who’re testing out some of the practices I’m creating for the new approach to homeschooling. Egan homeschooling!) I’ll be making a homeschool-specific version of this pattern and getting their feedback on it soon-ish.

Fingers crossed, we’ll come up with some practices that are awesome enough to include in the online homeschooling workshops I’ll be giving this coming summer, which I’ll then fine-tune and turn into our first Egan Homeschooling book.

For an eye-opening example of what schooling looks like when you don’t have shared values, see Zach Groshell’s story of a bottom-ranked school turning itself around.

I always think it’s funny when a large public high school is described as a “community”, when obviously, it’s like twelve communities trying very hard to not interact with each other.

The sole exception, of course, being Aesop’s Fables. Gosh, I love those.

And these values turn the plot: the first act ends when the three main characters are fired from Columbia, the “A plot” is about how to capture ghosts, the “B plot” is about how to ward off the EPA, and the denouement is a celebration of NYC.

I'm reminded of Willingham's statement that there's no one personality that all good teachers share, but all good teachers have a personality. I think the same could be said for values - there's no one set of values that makes the best school (though valuing learning usually helps).

The last generation leftists sure had values, even if they didn't call them that - for example, solidarity was pretty high up there. For the latest generation of leftists, any school that has a diversity and inclusion statement that they put into practice are living out their values. "Respect people's pronouns" is a value after all. Sadly there are lots of examples with a great diversity statement on their website and a very different reality in the corridors and locker rooms.

There's a long history in England of schools having named virtues and trying their best to "show, not tell" the virtues to their pupils. One the elite side, pretty much every famous school has a uniform and a motto (in Latin of course) and a list of virtues they live by. Harrow for example has Courage, Honour, Humility and Fellowship (https://www.harrowschool.org.uk/news-events/explore-harrow/our-values). "These values are nurtured in boys during their time at Harrow and form the basis of all that we do.", says their school policy. School uniforms as part of creating a school culture are quite normal in England. Meanwhile for children in London that are unlikely to go anywhere near an elite school, Michaela academy (called "Britain's strictest school" in the media and very proud of this) is all about its ethos and values.

I'm reading this from a UK perspective and going "Of course all our schools have named virtues!" though theory and practice are not always the same thing. At least in practice.

Yes, this is very rich. Virtue makes us come alive. How many young people would love to enter a true heroic training? To attend Hogwarts, and to truly feel that with great power comes great responsibility? Kids have incredible ability to learn on their own, but what adults can uniquely provide is an initiation into a community of value and mystery.

And I agree that choosing just a few virtues/values to start with is the way. We need to trust that living any specific virtue deeply (such as "justice") brings one into relationship with the field of other true virtues that exist in the "field of value".

I teach at an IB school and I am trying to lean into the heroic training aspect of virtue cultivation. As a whole, IB schools do a good job of stating their values, but rarely live them in valiant fashion. A common mistake is to espouse too many values and be unwilling to sacrifice any, which bottoms out in simple virtue signaling. Schools who live their values deeply as a community are a rare breed.