We are Surrounded by Mystery

The 52nd in the Egan Pattern Language

1. A problem

Kieran Egan put it snarkily:

I suppose, being a university professor dripping with awards and prizes, that I have played the schooling game well. But I was never sure what sense it all made.

Why did I have to learn to decline those Latin irregular nouns, or be able to prove that opposite interior angles of a parallelogram are congruent, or recall the provisions of the treaty of Ghent? Much of the time I and everyone I knew was bored with schooling, and had difficulty relating what was happening in class with human life and its enhancement.

My book is an attempt to show that, indeed, everything in the world is wonderful, but that schools are designed almost to disguise this slightly shameful fact.

We represent the world to children as mostly known and rather dull. The opposite is the case: we are surrounded by mystery, and what we know is fascinating.

My book is an attempt to show how we can reconceive the school and the process of education to engage students’ emotions and imaginations with knowledge.

–Kieran Egan, talking about his book The Future of Education, emphasis mine

At the heart of teaching is helping kids realize that what they’re studying has mattered to the people who first discovered (or created) it, so that sense of mattering can spread to the kids, too.

It’s a heckuva lot easier to do that when you can help them see our knowledge as an ice flow on a dark sea.

2. Basic plan

Call attention to the real mysteries that are already assumed in what you teach.

These can be past mysteries that kids get to experience vicariously through the eyes of the scientist/explorer/inventor who first shined light on it. Or they can be current mysteries that, fingers crossed, may be solved in the students’ lifetime. Or it can be some of the perpetual mysteries that it’s possible humanity will never understand.

3. What you might see

At the end of a lesson on the particle–wave duality of light, after everyone has seen that light gets places that only a wave could get to, but that whenever it lands, it lands as a dot, a student furrowing her brow and asking, “So basically… the universe is trolling us, right?”

4. Why?

Mystery tells the truth about the human condition.

If you train as a teacher, the first thing you’ll be told to do is simplify the material so it fits inside your students’ heads. Alas, if you succeed in efficiently presenting many small truths, you’ll accidentally communicate a big lie — that the world is orderly, and easily understood. When students struggle later, they’ll blame themselves — if they were only smarter, this would come naturally to them.

Nope. Egan, again:

We represent the world to children as mostly known and rather dull. The opposite is the case: we are surrounded by mystery, and what we know is fascinating.

When we reframe academic knowledge as ice floes in a dark sea, we flip the script: it’s dark, here. Ignorance is our natural state, and nothing to be ashamed of. Curiosity is a candle in the dark.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

In ancient Rome, mystery cults gained adherents by promising secret knowledge. To this day, Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Christianity put mystery at the center of worship. (And note that we’re in a moment when mystery-oriented varieties of religion are flourishing and rationally-oriented varieties dwindle.)

H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulu mythos taps into this: our much ballyhooed scientific understanding of the world is just scraping the top layer; beneath it is ominous darkness.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

It must be understood that PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding can carry a certain… cockiness? Watch as we shine light on everything, and make sense of the whole world!

This is part of why 👩🔬THE QUEST FOR TRUTH attracts haters. And, look, we’d be stupid to belittle what it’s gotten us!1 But our understanding of the world really does have limits, and those matter.

That there may be some permanent limits nudges us into IRONIC (😏) understanding.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Kids stuck on but this is BOOORING. (This pattern may be the “nuclear option” for cultivating interest and respect for a topic.)

7. Critical questions

Q: I thought you were a rationalist! A minute ago you cited religions (and Lovecraft) as examples of mystery. How can this be educational?

You also hear a love of mystery coming from the mouths of the very people who are pushing forward the boundaries of our understanding. Isaac Newton is reputed to have said:

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself, I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

– Isaac Newton, as cited by Wikiquotes2

Q: What do you mean by “mysteries we may never solve”?

I’m thinking of things like the hard problem of consciousness, the origin of the Universe (and whether there are things outside it, like God or values or other universes), the nature of time, the nature of numbers, what the first human language was, the causes of war and peace, and what the good life is.

Q: But surely we’ll figure those things out with enough time.

We might, but we might not. It may be that the tools to understand, say, consciousness, don’t exist within the Universe. (Read Erik Hoel if you’d like to understand this possibility better.)

8. Physical space

Nothing needed.

9. Who else is doing this?

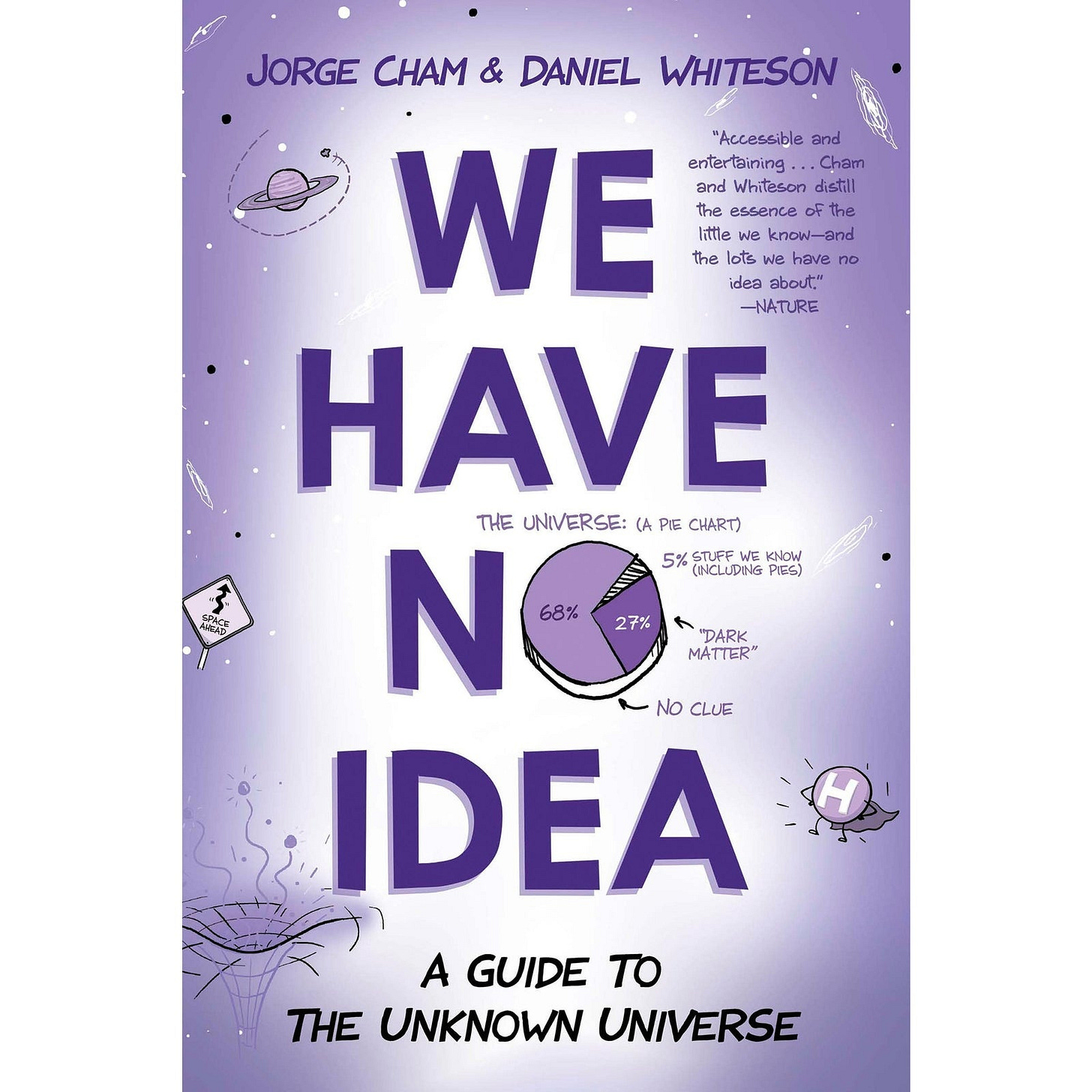

Mystery is the beating heart of one of the three best popular science books ever written:

Every chapter is on an honest-to-goodness mystery:

I haven’t, though, seen any courses that are organized on mystery.

How might we start small, now?

Whatever you’re teaching, identify something about it that scholars still don’t know (or disagree about). Unknown details can tell you about the limits of our data-gathering capabilities:

How many feral cats live in Rochester, Minnesota?

Even better, though, are the big things. A conversation with an LLM might be eye-opening:

Act as an expert in [subject], and give me a list of big open questions that scholars don't know the answers to.10. Related patterns

This comes up a lot in science. Secrets and Revelations° trades on this lust for the unknown, but steers kids towards a clear answer.

The joy of The Shrink Ray° is that it thrusts us viscerally into mystery. “The physicists Murray Gell-Mann struggled to understand what protons were made of” can be boring, but imagining yourself shrinking down to one-quadrillionth of your size and standing next to a single proton as you squint and see some things buzzing around violently inside… well, it’s less boring! (Ditto with expanding to be one octillion times your original size, and standing next to the ball of the entire observable Universe, which comes up to your chest. “What’s outside the observable Universe?” suddenly becomes a mystery with teeth!)

Afterword:

I’m about to review a book that, on the surface, seems to advocate for the precise opposite of what this pattern suggests: Just Tell Them: The Power of Explanations and Explicit Teaching, by Zach Groshell.

The thing is, I hope I’m really going to love it. I’ve been a fan of Groshell’s for a while — both his blog (Education Rickshaw) and his podcast (Progressively Incorrect) are a bulwark against the worst “let the kids figure everything out for themselves!” tendencies of progressivist education.

Which is all to say that “mystery” is not sufficient. We need clarity, too.

It’s a short book, and quite cheap on Kindle. If you’d like to grab a copy now, I’d love to have a conversation about it in the comments of my (coming) review.

I sometimes wonder if postmodern relativism — think of the grad student who lectures you on how “all knowledge is just a cultural construction” — could be cured by five minutes flipping through a civil engineering textbook.

Turns out this quote is only attested in a book about Newton from 1855 — about a 150 years after Newton died — so I’ve doubts as to whether he said it. The fact that scientists have loved to quote it ever since, though, proves my point nicely.