World Religions Everywhere

The 50th in the Egan Pattern Language

Note: I’m not dead! I got a particularly nasty case of pneumonia that knocked me out for a few weeks, and left me all-but-energyless for a month after.

I’m going to be tinkering with my writing schedule (see the “Afterword”), but look for a return to regular posts starting… now.

1. A problem

American schools1 tip-toe around religions for perfectly understandable reasons. The only trouble is that this leaves students stupid.

Religions are among the most powerful forces in humanity: they’ve been the glue holding societies together, they’ve driven (and forcibly held back!) progress, they’ve shaped the deepest convictions of billions of people. They massively influence law, economics, and global politics.

Ignoring world religions means ignoring how the world really works.

2. Basic plan

Don’t hide the world’s religions. In literature, don’t exclude religious stories. In art, don’t exclude religious paintings or sculpture. In history, don’t exclude the development of the major religions. In philosophy, don’t exclude religious questions and perspectives.

The subjects already teem with religious stuff; we don’t have to try to put it in so much as decide to stop keeping it out.

3. What you might see

In elementary school, you might see kids…

listening to a version of the Hindu epic The Mahabharata

practicing telling the story of Confucius, and Jewish wisdom stories

committing the numbered doctrines (e.g. the 10 Commandments, the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism, the Five Pillars of Islam…) to memory

In middle school, you might see kids…

hearing the big stories of the major world religions

visiting churches, mosques, synagogues, & temples

comparing versions of the afterlife across different religions

coloring maps of the most populous religions across the globe

finding inspiration in people like Gandhi, Black Elk, and Rabbi Akiva

In high school, you might see kids…

debating some of the big ideas that religions raise: is the world an illusion? How do we make sense of suffering? Does goodness have a grounding beyond human preference? Is mercy more important than justice?

reading classic books by religious thinkers that argue a thesis that people outside the religion can engage: book like C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, Abraham Joshua Heschel’s The Sabbath, Reza Aslan’s No God But God, Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse’s What Makes You Not a Buddhist, and Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian.

4. Why?

First, when schooling ignores religions, people latch onto unfathomably stupid beliefs about them.

Remember God debates on the internet in the 2000s? Remember how exasperating they were? On one side, you had people arguing that religion was “the root of all evil”. As someone who was active in the atheist community at the time, I can say that many of them really believed that defeating religion would usher in prosperity and enlightenment. On the other side, you had people arguing that world religions were never-ending fountains of profound wisdom. (Remarkably enough, this wisdom perfectly aligned with early-2000’s liberal values.) True Christianity/Islam/whatever, they held, would never harm a fly.

That these were both utterly indefensible views is probably best shown in the fact that even their advocates don’t advocate for them anymore.2

Second, when schooling ignores religions, people become blind to how religious our politics have become. Since the 2000s, both sides have been edging closer and closer to all-out Bible-thumping revival meetings than any kind of deliberative assembly. People confident they’re thinking rationally about policy are actually being controlled by some of the oldest, most irrational forces of psychology and anthropology. (I work hard to keep politics out of this newsletter, so I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to imagine what I might be thinking about here.)

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Humans seem to be naturally religious. Secular societies do exist, but even they seem to require a very rare set of conditions. Being interested in religion seems to be written into our species’ DNA more directly than, say, math or science.

This is all to say that religion so generally interesting, it’s ridiculous that many schools don’t already teach it.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

For a non-believer, Egan was quite religious,3 so it’s not surprising that he referenced religions frequently. I don’t think he ever came out and said this, but I read him as strongly implying that religion is, for some people, a way to speed run his five ways of understanding.

To wit:

SOMATIC (🤸♀️): religions anchor understanding in the body through PHYSICAL RITUALS and SENSORY EXPERIENCES. You bow in prayer, you light a candle, you feel the tune inside you reverberating with the tune from the people standing around you… and this triggers a conviction that these things matter. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

MYTHIC (🧙♂️): religions teach through STORIES that lodge themselves deep in your memory. These are tales of spiritual entities and cosmic battles — narratives built on EMOTIONAL BINARIES and chockablock with VIVID MENTAL IMAGES that stick around long after they’re told.

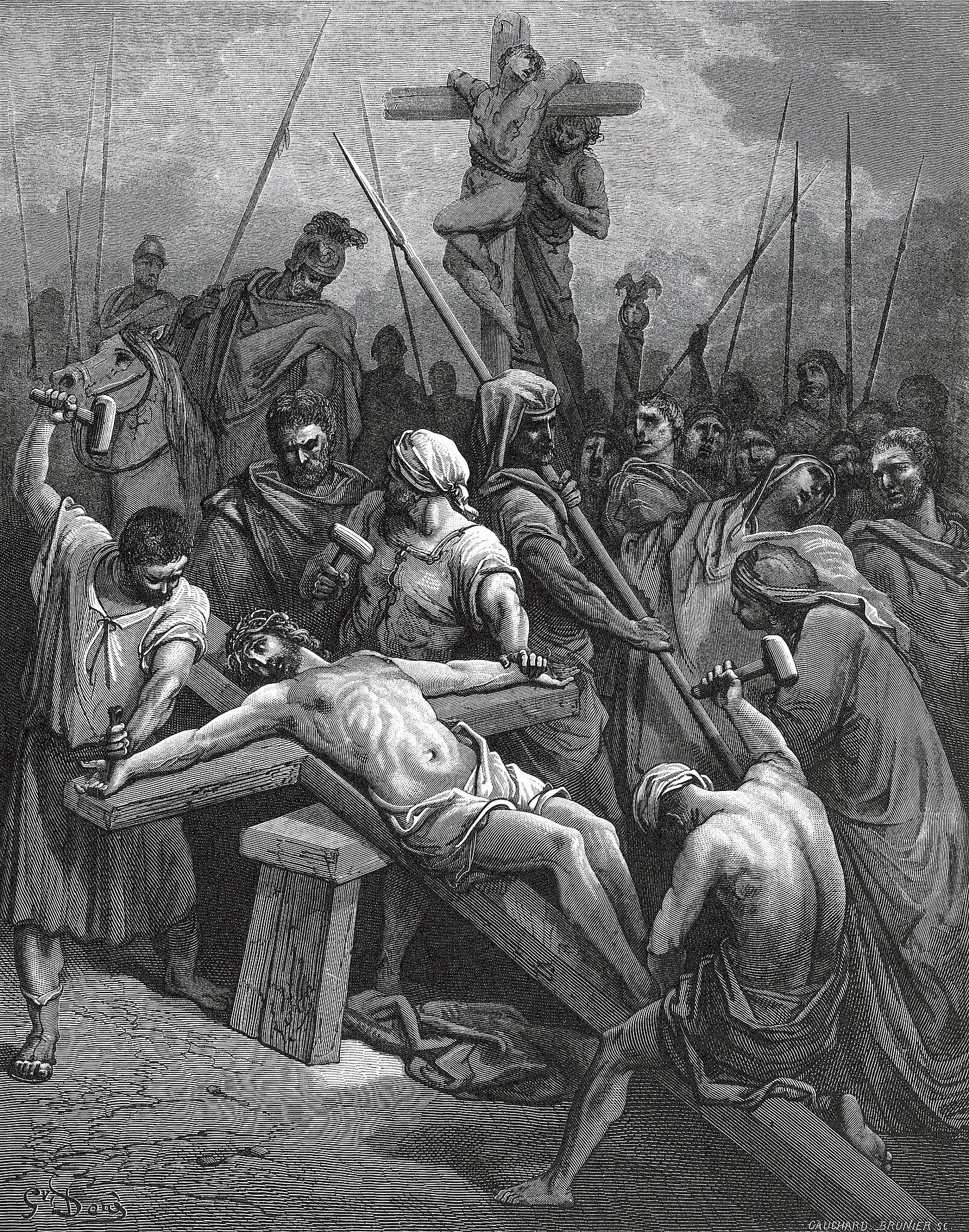

ROMANTIC (🦹♂️): religions tap into (and maybe help create) our longing for THE EXTRAORDINARY. Adherents stock their imaginations with HEROES: saints who renounce wealth, prophets who confront empires, and martyrs who endure unimaginable trials. Their stories inspire AWE; they invite you to join in and see your own life as a cosmic adventure.

PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬): all these stories prompt BIG QUESTIONS, and religions (now through theologians) work hard to find answers. They’re launched onto the QUEST FOR (ABSTRACT) TRUTH, and put together SYSTEMS that try to fit all the facts. Thus far, in no religion have theologians succeeded in creating one system of thought that all their co-religionists find convincing; thus, we see BATTLES OF IDEAS between the different camps.

IRONIC (😏): in every religion, some theology-minded people have the insight that maybe the truth of ultimate reality can’t fit into human minds. Maybe the debates between determinism & free will, love & justice, can’t have a perfect answer in this world. Maybe God (or Brahman, Nirvana, the Dao, etc.) is beyond what words and concepts can describe.

This can cause profound dread, but on the other side of the dark night of the soul4 is a new sense of levity, BUOYANCY. It’s a way of understanding the world that is okay that it lacks a perfectly logical foundation. It sees God (etc.) as THE GREAT MYSTERY, and is thankful for the MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES that we can begin to understand it through.

(Just to be clear, this isn’t anything Egan was explicit about — it’s probably the interpretation of Egan you’d expect from a former Christian who endeavored to become a theologian and lost his faith studying history and world religions.)

6. This might be especially useful for…

Kids who feel that school’s fake, and long for something that feels real.

7. Critical questions

Q: Excuse me! I have a snarky question for you!

Y’know what? Our readership of — whoa, nearly 2,000 subscribers! — probably has so many questions (snarky and otherwise) that I’m not even going to try to guess them. Instead, I invite you to ask your honest questions in the comments below. I’ll answer them there, and at the end of the week edit this post to put the best ones up here.

HOP IN THE POOL, THE WATER’S FINE! Just become a subscriber to join in the comments conversation. Become a PAID subscriber to show your support for this sort of educational thinking that’s on the edge of respectability.

8. Physical space

Obviously, religions have a lot to say about how you set up a physical space! But we’re not creating sacred spaces — we’re learning about religions. So I don’t imagine there’s anything unusual we’ll want to do with the classroom.

9. Who else is doing this?

My hunch on this is “everyone outside America”. American schools seem to find religion more awkward to talk about than other societies that I’m aware of — perhaps because we’re more religious than other Western nations.

Or perhaps I’m just wrong about this! If anyone has any knowledge (abstract or first-hand), let me know in the comments.

How might we start small, now?

If you want to do this an American public school and don’t want to get a letter from the Freedom from Religion Foundation, leafing through Stephen Prothero’s book Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know — and Doesn’t might be a good place to start identifying what’s kosher.

Prothero’s one of my favorite writers on religion: he’s an academic who writes clearly and answers questions people actually want to know. He went on to write the excellent God is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions that Run the World (and Why Their Differences Matter), which — if you don’t know a lot about religion — might be a good book to read next. It’s a favorite of mine. When I taught high-school seminars on world religions, I’d have students read its chapters against those from Huston Smith’s classic The World’s Religions, which argues that all religions are, at their cores, the same.

Oh, also, the never-boring John Green has a new YouTube series on religion! (Did you know that, prior to becoming a famous YouTuber and novelist, he was a chaplain?) If you have older kids, it might be a wonderful place to start. If you (or your kids) have interest beyond that, I heartily recommend anything on the channel Religion for Breakfast, which is made by a PhD in religious studies who I’ve found can be trusted to explain the contemporary scholarly consensus on controversial questions about religions.

10. Related patterns

As a general pattern that advocates including a major aspect of human society that’s been stripped out of the curriculum, it parallels Philosophy Everywhere°, Everyone Learns Law° Everyone Learns Economics°, and Customs & Cultures°.

And like them, it comes into classrooms through more specific patterns — Epic Stories° being the main way it enters elementary and middle school. As religions talk about existential and cosmological issues, it’s also a way to make Asking the Big Questions° natural.

Finally, it’s a lead-in to one of my favorite patterns, Worldviews° — in which we help high schoolers spot the biggest ideas that run the world.

Afterword:

After a two-month hiatus, I’m excited to return to writing here!

(I got a bad case of pneumonia, which at one point left me shifting randomly between sweating profusely, and wrapped in blankets in a sweltering room shuddering from the cold. Lots of opportunities to reflect on how the immune system works, though.)

I’m going to step back on my regular posting of patterns here, though. Expect a new pattern once every two weeks. This should allow me more time to take on side writing projects, many of which will also appear here.

Additionally, work with the Skeleton Army continues, and I’m currently planning to walk through what a full elementary Egan homeschooling curriculum can look like in an online course I’ll be making this summer! (It seems like a natural step before producing the actual book.)

In this lacuna of posts, I’ve been laying the foundations for a handful of tremendously exciting projects to forward Egan education in the world. Look for the first of them to be talked about within the week.

Usually I try to keep these patterns international; my apologies to readers in countries more sensible about teaching world religions than the United States. (I’d actually love to hear how well/poorly your system does with this.)

The New Atheists in particular seem to have matured in their thinking about religion. For what it’s worth, I still love reading Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. When they write about their own disciplines, they’re typically brilliant; when they write about religion, they make some excellent points (amongst the occasional dumb ones).

As a young Catholic, Egan became a novice in a Franciscan monastery. He eventually left the faith, but to the end of his days described himself as “an atheist, but a Catholic atheist”. He reflected on the difference between contemporary schools and his religious education in my favorite essay of his, “Where is the Song in the Heart of Education?”

I wonder if THE DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL can actually be seen as a tool. Hmm…

Unfortunately, I think the reason this doesn't exist in most schools is that parents don't want it.

In particular, the vast majority of the most religious people that I know would rather stop at the philosophic stage. They think that their denomination has the right answers to just about everything, and the main reason to learn about other religious perspectives is to be able to show why they're wrong.

After emerging from my own dark night of the soul several years ago with my faith mostly intact, I find this disappointing. But I don't see how to implement something like this without being condemned for corrupting children's minds. (Something like that happened to Socrates, for example...)

Non-snarky question: How do you resolve the tension between the rationalistic bent of Eganism and the non-rationalistic stance of most religions? Seems like the attentive student will ask "But (charitably) it's all just allegory, right?".

Is the truthful answer something like "We study this for pragmatic reasons, because it's deeply ingrained in culture."? And doesn't that (implicitly) lead to the punchline "But we know better."?