Geography in elementary school

Or: how to plant the world in your head

Table of Contents

Part 1: Why geography?

Part 2: How’s geography done now?

Part 3: What geography can look like

1: Why geography?

Our big fat hairy problem

Most people know absurdly little about the rest of the world.

Survey after survey, for example, finds that most Americans can’t locate on a map the countries that their nation is currently at war with. But factoids like this undersell the depth of our problem. I worked with a high school student once who didn’t know about the Pacific Ocean. He had gone to “good” schools — some of the best-rated ones in the Seattle suburbs. He was smart and curious — when I found this out, we had just finished a discussion about the (underrated) role Rosalind Franklin played in discovering that DNA was the genetic code. He was even rich — his family owned two homes, one of which was on the shore of Puget Sound!

But when I mentioned the Pacific Ocean, he politely asked what I was talking about. When I pulled up Google Maps and zoomed out from our location, his eyes went wide, and he looked embarrassed. He lived on Earth’s single largest geographical feature, and he didn’t know about it. (“What did you think was between here and China?” I asked him. He answered sheepishly: “You know, I never thought about that.”)

He’s not even a statistical fluke — the idea for the TV show Where in the World is Carmen San Diego? was sparked when producer Howard Blumenthal saw a survey reporting that 1 in 4 Americans couldn’t find the Pacific Ocean on a map.

What geography can do for us

We’re starting from a very low point, and almost anything we do can improve this. But we don’t want to just pull down low-hanging fruit. The true purpose of geography isn’t merely to locate places on a map — it’s to help us connect everything that kids learn.

Too often in schools, knowledge appears as facts fallen from heaven (or ginned up in a dark textbook factory). But knowledge comes from people, and people come from places. Literature, for example, comes from minds of oddballs who were shaped by their oddball cultures which were shaped by their oddball environments. The same is true of science, math, sports, and everything else.

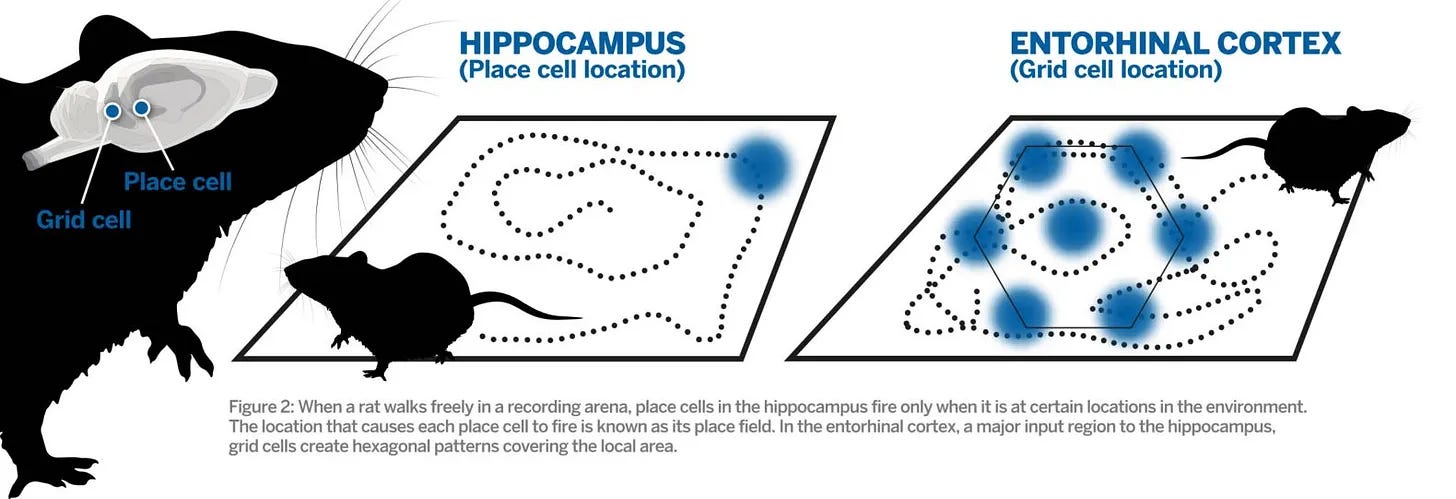

There are many ways to connect information, and in the wireframes to come, we’ll be pursuing all of them! But our location-sense is cognitively privileged. Grid cells, tucked just behind the eyes, map the structure of whatever space you’re in, while place cells in the hippocampus fire to mark your current location.

Helping kids learn a lot of geography is the first step toward rehumanizing the entire curriculum.

2: How’s geography done now?

As the first post in our 2026 series of “wireframes”, this is a good moment to show how we’re taking a more radical approach to education than you might guess.

The story of 20th and 21st century education has been the war between educational progressivists and educational traditionalists. And in this war, we’re taking a new, third side. If we do this right, this year we’ll be sketching out a new hope for schooling that incorporates some of the strengths of each while avoiding both their weaknesses and the disasters that come when folk try to combine them.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Progressivism, traditionalism — are we talking politics?

We are not. While both educational progressivism and political progressivism were once joined at the hip more than a century ago (see: John Dewey), the movements have each drifted a lot, and what once might have seemed like contradictions (Communist revolutionaries pushing classical education, Christian über-traditionalists practicing unschooling) are much more common than you’d think.

Everyone defines educational progressivism and educational traditionalism (which I’ll hereafter often shorten to “progressivism” and “traditionalism”) differently, which is fair. Both are blurry movements, containing strange bedfellows. But to talk about these, we’ll need to distill an essence of each. For the moment, we’ll say…

the battle-cry of educational progressivism is to set kids free to follow their passions!

the battle-cry of educational traditionalism is to equip kids with the best ideas anyone’s ever thought or said!

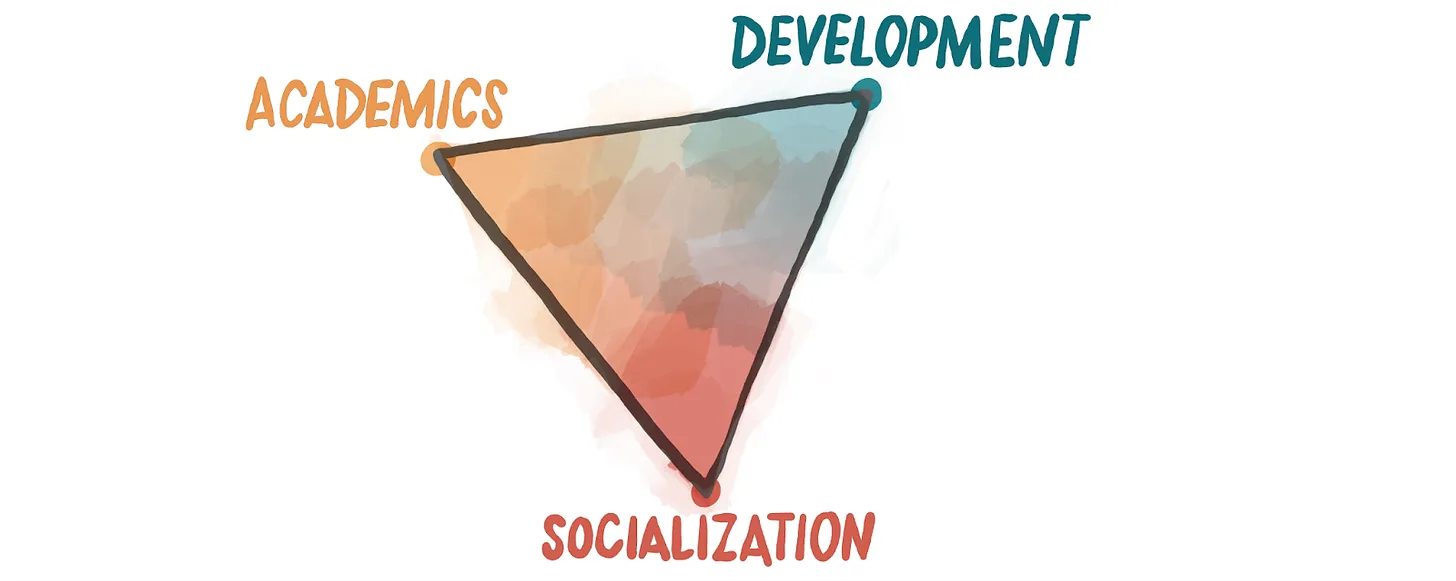

From these everything else flows. Are students explorers (progressivism) or apprentices (traditionalism)? Should we focus on a student’s whole life, or their intellectual formation? Is a teacher a guide, or a content expert? Do we start from a kid’s interests, or from a summary of the academic content? Do we want practice to be experienced in natural contexts, or done in drills?

I.I.: This seems familiar.

It should be! This, in fact, is the one educational war that all other debates in education are mere skirmishes in. Whole philosophies of education can be seen as sitting on one side of the great divide: unschooling, world-schooling, Reggio Emilia, and project-based studies all fall on the “progressivist” side, while classical schooling, mastery learning, and the Great Books approach fall on the “traditionalist” side.

They show up in my book review, too, if in disguise. In the “SAD triangle”, progressivists are the people who have their home in the “development” corner and traditionalists are the folk who live in the “academic” corner. (They both send their scouts down into the “socialization” corner, though they have different opinions on what this should mean.)

We’re going to be talking about these approaches to education a lot, so it makes sense to personify them. Meet Poppy the Progressivist, and Theresa the Traditionalist!

To see how odd our proposal for geography is, it makes sense to quickly look at how they each do it.

How progressivists do geography

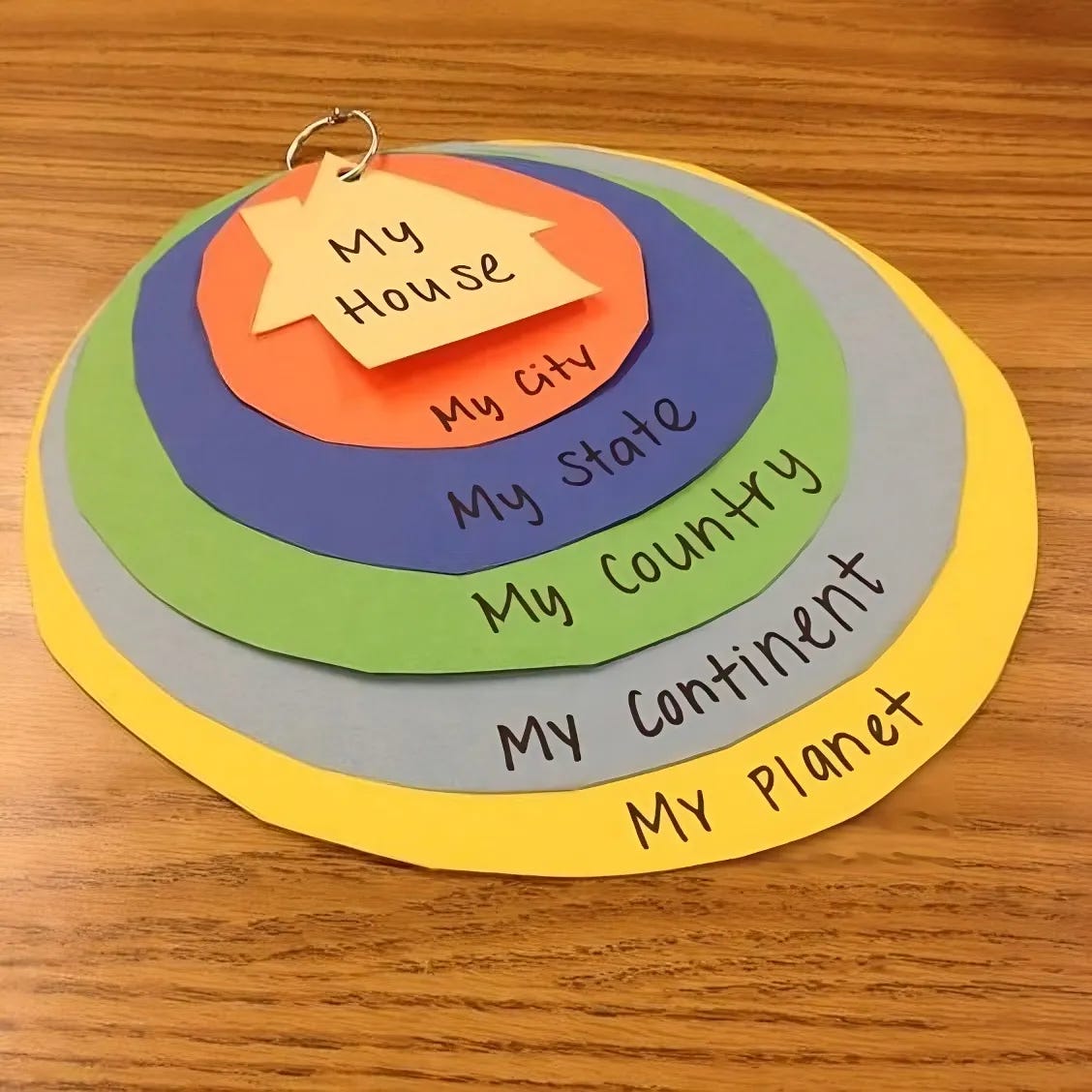

If you asked Poppy the Progressivist how she teaches geography, she might respond by saying that it’s an essential part of social studies. (“Social studies” itself is a subject created by early progressivists to give meaning to history and geography.) As such, kids should learn it as part of the “expanding horizons” model:

Kids, she might say, can best understand what they themselves have touched, tasted, smelled, heard, and seen. As such, it makes sense to build on this, beginning in the early years with the self, and gradually working outwards:

kindergarten: themselves

grade 1: their families

grade 2: their neighborhood

grade 3: their city

grade 4: their state

grade 5: their country

grade 6: the contemporary world

In the future, we’ll be exploring things that progressivists get brilliantly right… but this isn’t one of them. The “expanding horizons” model diminished learning about the rest of the world precisely in the grades when it’s easiest! It digs a hole that most students never climb out of: by the time they get to middle and high school, most of their teachers don’t want to be doing anything as rudimentary as memorizing maps, so their classes jump to “higher level” understandings… with students who don’t know that there’s such a thing as the Pacific Ocean.

This is not a recipe for a deep, connected understanding of the world. When progressivist classrooms work, they cultivate curiosity, collaboration, and moral seriousness — but without a shared map of the world, those virtues often float unmoored. Expanding horizons is the original sin of 20th century education. It began as an attempt to honor children’s lived worlds… and ended by quietly erasing the rest of the planet.

How traditionalists do geography

In response to this, modern-day traditionalists present an approach to geography that, on the surface, seems like a solution: they have students

memorize names of countries and capitals, and

label maps.

Obviously, this is better than holding off on geography. But we should be clear that this isn’t the educational revolution we’re working toward. The goal of geography isn’t to be able to write names on a map — this makes a weirdly literal version of the old mistake of “mistaking the map for the territory”!

Kieran Egan put this mistake memorably:

“The point is not to get the symbolic codes as they exist in books into the students’ minds. We can of course do that – training students to be rather ineffective ‘copies’ of books. Rather, the teaching task is to reconstitute the inert symbolic code into living human knowledge.

The point that knowledge is ‘living’ seems crucial.”

– Children’s Minds, Talking Rabbits, and Clockwork Oranges, p. 51

We want living knowledge. Any geography curriculum worthy of our kids should expand their sense of what reality is. It should offer glimpses into other possible ways of life. It should help them fall in love with the world!

So… how can we do that?

3: What geography can look like (in elementary school)

“Geography” is a rope made up of multiple threads:

Maps

Marvels

Navigation

Each of these threads will continue through elementary school, middle school, and high school, evolving as it goes forward. Today, I’ll unveil our thoughts on what these can look like in elementary school. In the next wireframe post, I’ll show off what these can become in middle and high school (and also sketch out some ideas for preschool and kindergarten).

For each of these threads, we’ll give at least one practice — an intellectually rich, emotionally meaningful activity you can engage in with your kids, either as a parent, teacher, or both.

Thread 1: Maps

In first grade, quickly become familiar with the biggest features of the world, so they can put everything else they learn into the full context.

A note on grade levels

To plan to launch actual schools, we need to be specific, but if you're a parent or classroom teacher, adapt these however you'd like. If your kids are starting geography in second grade or fifth grade or high school, they still might want to start here. If they're three years old and super into maps, sure, heck, go for it! If you're wanting to give yourself the geography education you've always dreamed of, knock yourself out.

Assume that every grade level recommendation is like this.Practice A: Name the big things

Begin with the continents, then move to the oceans. (If you want to go beyond that, and don’t want to move onto the next practice, feel free to linger here and add on the major rivers and mountain ranges.)

You might want to proceed at a rate of adding one place per day, of course reviewing the ones you’ve learned before. Very quickly, and with little work, you’ll get the biggest pieces of the world into your heads.

How can we make “Maps” meaningful to everyone?

Narrativize the practice, of course!

A note on "narrativizing"

If your kids are Ravenclaws for geography — that is, if they’re the sorts of weirdos born with a penchant for flipping through old copies of National Geographic — then the above might be enough! But if they’re not, then you might want some more help. (This is especially true if you’re a classroom teacher.)

This is where Alessandro’s genius comes in. He’s added something to the standard repertoire of Egan tools: how to narrativize everything. Stories are, of course, the most powerful tool we have in communicating with other humans. When we say “narrativize”, though, we don’t necessarily mean to turn something into a literal story. Instead (following Egan) we mean to apply some of the deeper aspects of how stories work.

(This, by the way, is what every professional communicator does when they need to communicate some non-story thing, be they a documentary filmmaker, a marketer, or a YouTuber.)

Kieran Egan looked at stories and saw what he called MYTHIC (🧙♂️) tools — 🧙♂️EMOTIONAL BINARIES, 🧙♂️METAPHORS, 🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGES, and more. Alessandro saw something else: that how a good story progresses is crucial, too. Nearly all good stories follow a certain pattern. Exactly what this pattern is has been described differently by people as diverse as Aristotle, the novel editor Shawn Coyne, and the comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell. Alessandro drew on the work of Egan’s longtime collaborator Mark Fettes, who was himself drawing from Gregory Cajete, the Native American scholar of religion and philosophy.

Cajete observed that Indigenous learning often followed four phases: orientation, complication, transformation, and integration. Fettes observed that these look quite a lot like the beats of a story:

1. We begin with the orientation, where we experience something that pulls us in, calling us toward something that matters and asks for our attention and commitment.

2. We move to the complication, where we step into the story and go through difficulties that push us to grow.

3. We crest with the transformation, where we discover that we’re stronger than we had thought as we face (and resolve) challenges.

4. We return home with the integration, where we discover new insight from the journey we’ve taken.

And Alessandro has been working to develop these as a way to more fully Eganize everything.

I.I.: Dammit, Brandon, I’m a parent, not an inspirational classroom teacher!

That’s why "narrativizing" is most assuredly optional for parents. If you’d like to skip this, go for it. But if you do, look for other opportunities to create experiences that have coherence, meaning, and continuity, and that are rooted in a deep sense of why what you’re learning matters. Those aren’t optional — they’re the whole game! And they’re what narratives excel at doing.

I.I.: Ah, this is like “hooks”!

Alessandro hates that term —– to him, it smacks of intellectual cheapness, a "hack" one might use at just the beginning of a lesson. We narrativize to generate profound interest (“wonder”), and we want to fuel a journey that requires effort.

But I’m a yes–and guy, so I’m okay with being positive on “hooks”, so long as we understand that it’s just the beginning.Consider doing the “Name the big things” practice in these four phases:

Phase 1: Orient

Kids below the age of seven famously have trouble understanding what a map actually is — they view it as just another picture, and miss that every part of it “maps” onto the world. (This was discovered by the progressivist psychologist Jean Piaget, and was another reason geography has been slowly removed from the early grades.) We can use the cognitive tool of 🧙♂️ROLE-PLAYING to help them understand this more quickly: just have them pretend they’re a bird.

Start by having them imagine that they’re a blackbird flying above you in the room you’re in, and ask them what they might see, looking down. Have them draw that on a paper, and do it along with them. Repeat this on a playground: if you were a hawk, what would you see? Then do it again for your whole building or neighborhood.

Jean Piaget was (somewhat) right when he said that young kids struggle to learn certain types of abstractions — but with the tools of the imagination, we can de-abstract them, and make them easy.

Phase 2: Complicate

After drawing local spaces, go bigger: look at a map of your town, and imagine it as something you might see if you were in an airplane. Look at a map of your country, and imagine it as what you might see from a rocket. Look at a map of the world, and imagine it as what you might see if you stood on the Moon.

Phase 3: Transform

After you learn each continent/ocean, create something to hold that knowledge forever: a memory card to put in your MEMORY BOX°. Ideally, you can make your card beautiful, perhaps tracing an image of South America on one side, and writing a 🧙♂️SIMPLE QUESTION like “what continent is this?” underneath.

Alternatively, you could write down a mnemonic you’ve learned, like “Panicked Alpacas Ignore Stomping Anteaters” (to learn the seven oceans from biggest to smallest).1 Feel free to set that to a 🧙♂️SONG.

In your daily memory box practice, you’ll be doing spaced repetition review of this (along with everything else you’ve chosen to remember).

Phase 4: Integrate

After you’ve succeeded at learning the continents and oceans, you can take a breather and review. You can play a 🧙♂️GAME (spin a globe, close one eye, and in thirty seconds name all the places you can see), but the goal of “review” here isn’t just cognitive but existential. You’ve gone through this work. You’ve become a master of the names of the world! What questions do you have, now? Where might you like to go next?

A note on local geography

This newsletter reaches a global audience, so in this wireframe, we’ll be dealing with global geography… but we each live in a particular place. That needs to come into our geography curriculum, too.

Our idea for the moment is to spend one week each month — the second whole week, say — on some rotating aspect of local geography. So, in the second week of September, you could focus on the geography of your country. In the second week of October, you could focus on the geography of your state/province/territory. And in the second week of November, you could focus on the geography of your city. In December, you can start back up with your country, again.Thread 2: Marvels

The world is full of marvels — wondrous places that evoke strong emotions and stick in our memory.

Fantastic tales of painted deserts, impossibly long walls, cities carved from stone… wonders like this have always been how humans are introduced to the wider world. In this thread — coming short on the heels of the last one — we’re going to experience the marvels of the world as fully as we can (without getting on a plane).

This will be the core of our elementary school geography curriculum. The easiest way to do this is to obsessively read some books, which you’ll make part of your canon.

A note on building your canon

An Egan education can be weighed in books, but all books aren’t equal. In the words of Francis "The Scientific Method" Bacon:

"Some books are to be tasted,

others to be swallowed,

and some few to be chewed and digested…"

There are a few great books that are so rich that they can only be digested over years. We’ll be building parts of our curriculum on a few such books. We recommend —— so far as you’re able —— purchasing these in hardcover, and perhaps storing them on a special shelf.For geography, our canon includes first and foremost the titles in the Atlas Obscura series. If your kids are young, the first book to get is The Atlas Obscura Explorer’s Guide for the Most Adventurous Kid. My GOODNESS this is a great book. Each two-page spread features one truly amazing place in the world, gorgeously illustrated, and paired with a couple paragraphs that are genuinely interesting to read.

The next book you’ll want is the original adult version: Atlas Obscura: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders. It has much more in it, and great photos to boot. And after that, if your kid loves animals and plants (which is almost coterminous with “if they are a kid”?) you’ll probably want Atlas Obscura Wildlife: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders.2

How can we make “Marvels” meaningful to everyone?

Again, if you’re working with a geography Ravenclaw, you might just be able to plunge into these books! Adding one each day (for perhaps 4 days/week) might be a good pace to shoot for, and you’ll probably want to make each into a memory card. But if you’d like to bring out the big guns, oh yes, we have ideas for you:

Phase 1: Orient

You might introduce the idea of “marvels” by first identifying somewhere marvelous within driving distance. Prepare kids to enjoy it by first telling a story about it, then take them there to experience it with 🤸♀️MOVEMENT (run around it, climb on trees) and their 🤸♀️SENSES. Blindfold them and have them explore the place by sound and smell! (We’ll be having a lot more to say about how you might do something like this when we get to our “Science” wireframe. In the meantime, look to Egan collaborator Gillian Judson’s A Walking Curriculum for inspiration.)

Then suggest something to your kids: if your local area holds a spot as amazing as that place… what marvels might the whole world hold? Wouldn’t it be great if someone had gone on an adventure to discover all those marvels? And wouldn’t it be great if they had written a book to collect them?

Then hand them the first book. Invite them to flip around it, and choose one marvel to focus on the next day.

Phase 2: Complicate

Begin by reading the entry from the book, but don’t stop there — treat it as a springboard to experiencing the place in more imaginative detail. Use the MYTHIC (🧙♂️) tools to go deeper:

read a 🧙♂️STORY about why Galileo’s middle finger is on display in Florence

listen to a traditional 🧙♂️SONG from the Ethiopians who built the Abuna Yemata Guh church

spin 🧙♂️METAPHORS to try to make sense of whatever the Antikythera Mechanism did

create a 🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGE of the world’s largest ball of paint as it might look if it were in your room

And find a high-quality image of the place, and use 🤸♀️YOUR SENSES to imagine you’re there, touching, smelling, hearing, and seeing it. (We’ll have much much more to say about how to do this in our wireframe about Art. In the meantime, you can look at Luc Travers’s classic book, Touching the Art.)

Phase 3: Transform

On a notecard, capture something about the marvel you’d like to remember forever, and place it in your memory box as a gift to your future self.

Phase 4: Integrate

Make a master list of marvels with

their names

what they are, and

where they are.

Each week, have your kids stand by a map or globe and (as you read off the list) point to where the marvel is as quickly as they can.

Now, whenever you think of that country/state/city, you’ll have something vivid to connect to it.

A note on scheduling

Alessandro and I look forward to the day when we have this whole curriculum —— every topic, every year —— fleshed out in so much detail that we can give specific advice as to how long a family/classroom might want to schedule for these practices. We're definitely in danger of overwhelming education with too many delightful things to do. We'll only be able to winnow these down after we finish publishing these at the end of 2026.

In the meantime, feel free to play with these however you see fit.Thread 3: Navigation

We stand by the two practices above, but if you were to do them, you might still not free your kids from a core problem of educational traditionalism — helping them see that their books actually describe real places in the real world. All of these marvels can exist in the same mental category of “Gotham City” and “Neverland”.

What we need is a series of practices that helps kids see these places as being just as real as the buildings around them. So here are five. You might want to move through them in order, but the latter ones especially are rich, and can be productively engaged for years.

Practice A: Cardinal directions

We orient ourselves with the cardinal directions of north, east, south, and west. The trouble is that even when kids learn about these, they can easily stay mere abstractions. How can we constantly think with these?

Make cards for the cardinal directions, and post them in different rooms of your home/school. On the north walls, put up a card that says “NORTH”, and so on for the other directions. Then, start referring to them casually as you talk about anything and everything. (If someone asks “where’s the stapler?” you can say “on the bookshelf on the east wall”.)

Of course, we can make this easier by employing some cognitive tools — particularly 🧙♂️METAPHORS and 🧙♂️IMAGES. (The rest of this post will assume that you live in the northern hemisphere. My apologies to LiD director Shelley Smith and the other ~10% of readers on Earth’s unpopular bottom…)

north: write this in blue (for “cold”) and draw a polar bear

south: write it in green (for the tropics) and draw your favorite rainforest animal

east: write it in yellow (for the sunrise) and draw the Sun going ↑

west: write it in red (for the sunset) and draw Sun going ↓

Practice B: The walls are glass

Once you’ve gotten used to using the cardinal directions, you can connect them to your marvels. The most straightforward way to do this is (obviously) to imagine that an evil witch has turned all of the walls of your home/school to glass.

Now, what can you see?

To warm up, you might want to start with things inside your building. Ask everyone to point to the nearest toilet, or the nearest fridge. In your home, where’s the washing machine? In your school, where’s the gymnasium?

Once you’ve gotten good at this, bring in the world outside. Where’s a favorite tree? A favorite playground? The local liquor store?

Then, after you’ve gotten good at that, you can do the same things for the places and marvels you’ve been learning. In what direction is the Taj Mahal? The Mariana Trench?

Note: to pull this part off, you’ll want to imagine that

you have really, really good vision, and also that

the world is flat — otherwise, the things far away are hidden under the horizon.

You can either tell your kids this, or let your kids bring it up.3 But all this works using your building as a compass — how can you know the cardinal directions when you’re outside?

Practice C: The path of the Sun

Help your kids learn to navigate outside in the daytime. The Sun is what gives meaning to those cardinal directions in the first place — north, south, east, and west weren’t the inventions of some mad cartographer, but fall out of the single most important fact in astronomy: the Sun rises in a predictable spot, traces a precise arc across the sky, and sets in an opposite predictable spot.

I.I.: Didn’t we already teach that with those direction cards?

We did, and that’s unfortunate… because what we drew there was sort of a lie! Unless you live in the tropics, the Sun never actually rises straight to your east; it actually rises in the southeast, and sets in the southwest. (Precisely how far south depends on what season it is.)

If you know what time it is, and the Sun is out, you can immediately glean which way is north. (The Moon, too — though for that, look for the next post. In the meantime, take a look at the pattern Track the Sky°.)

Practice D: The path of the stars

Help your kids navigate at night. When the sky is clear, you can do the exact same thing with the stars. This, however, requires learning at least a handful of the major constellations that are visible at your latitude.

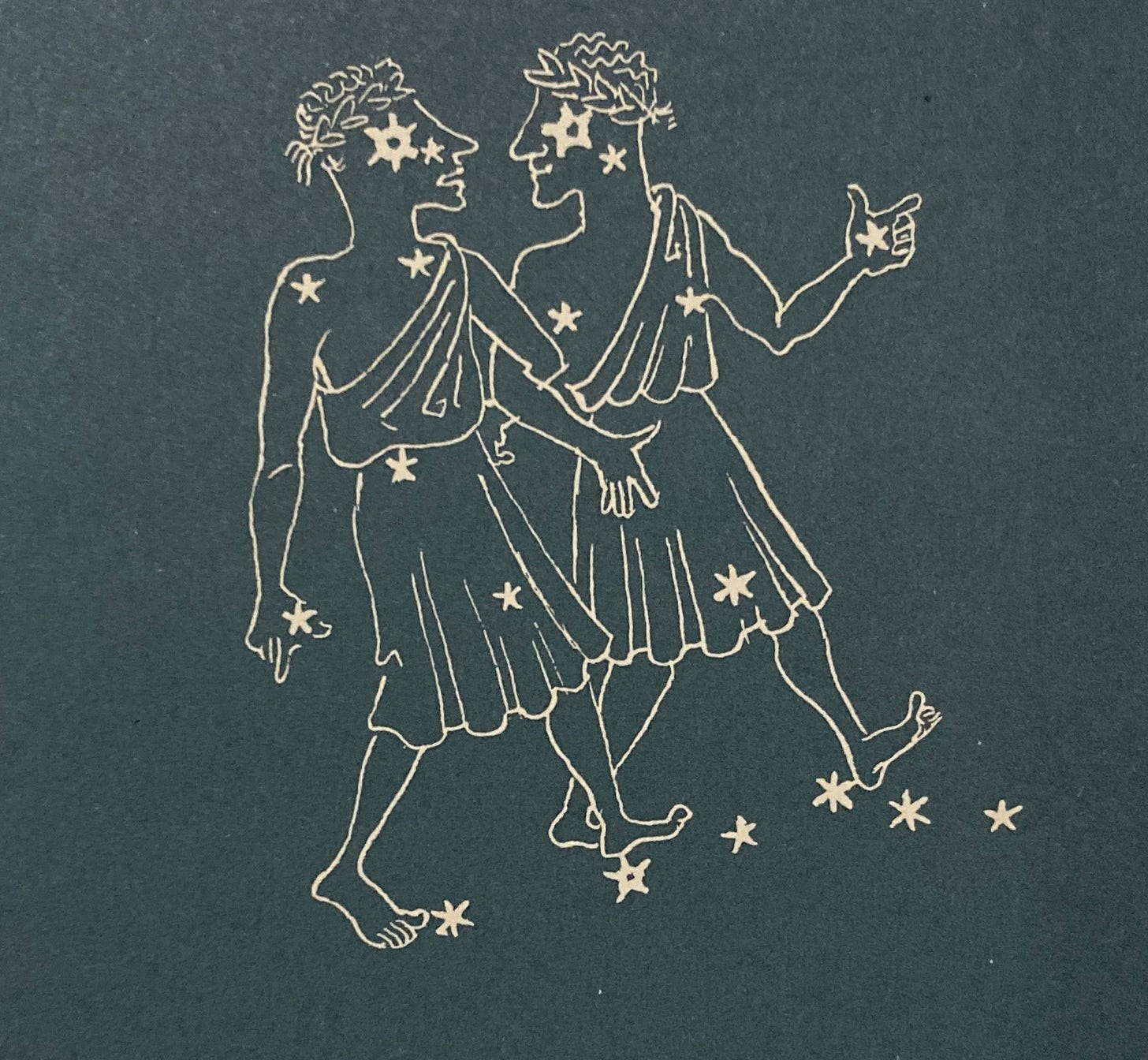

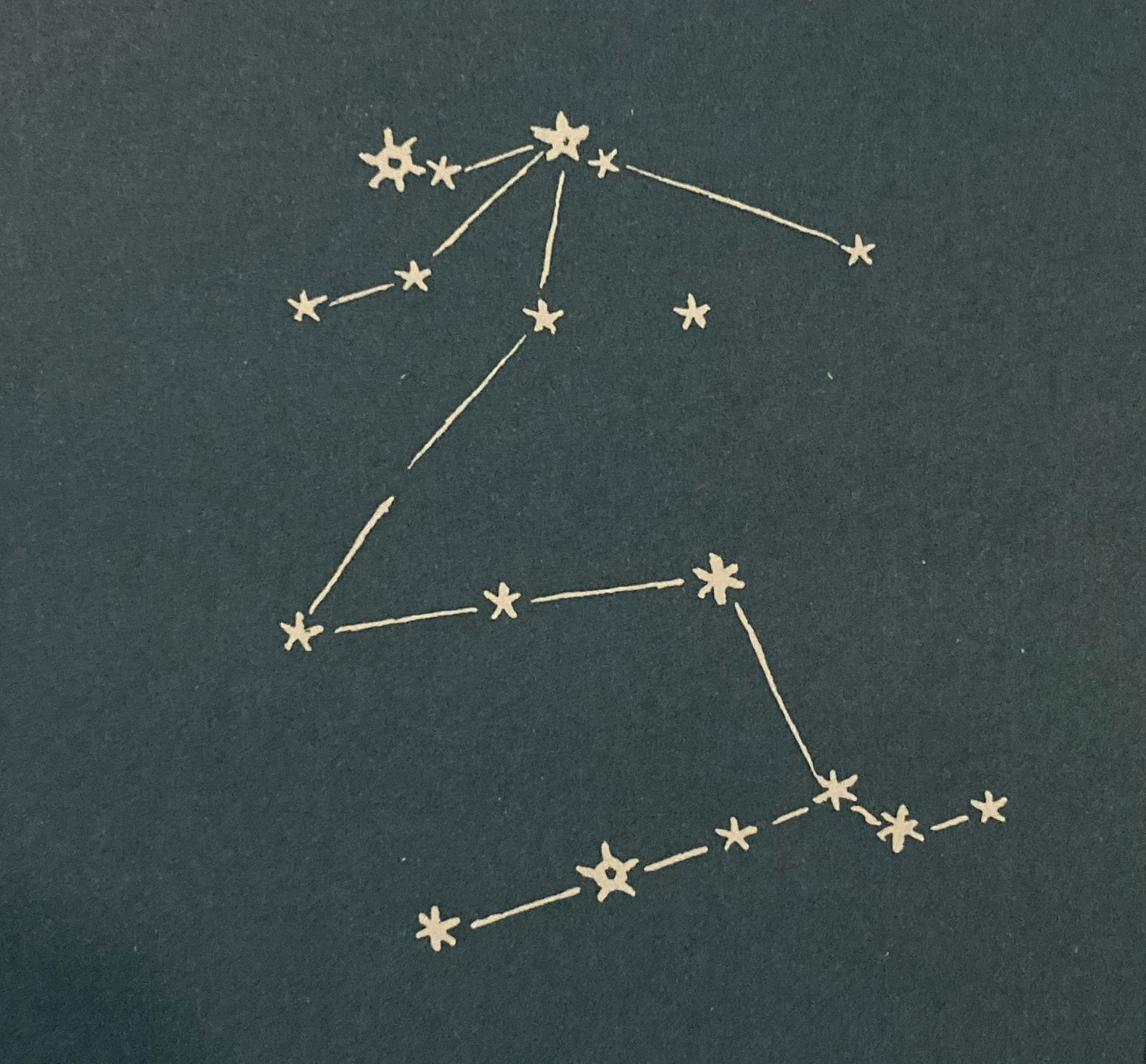

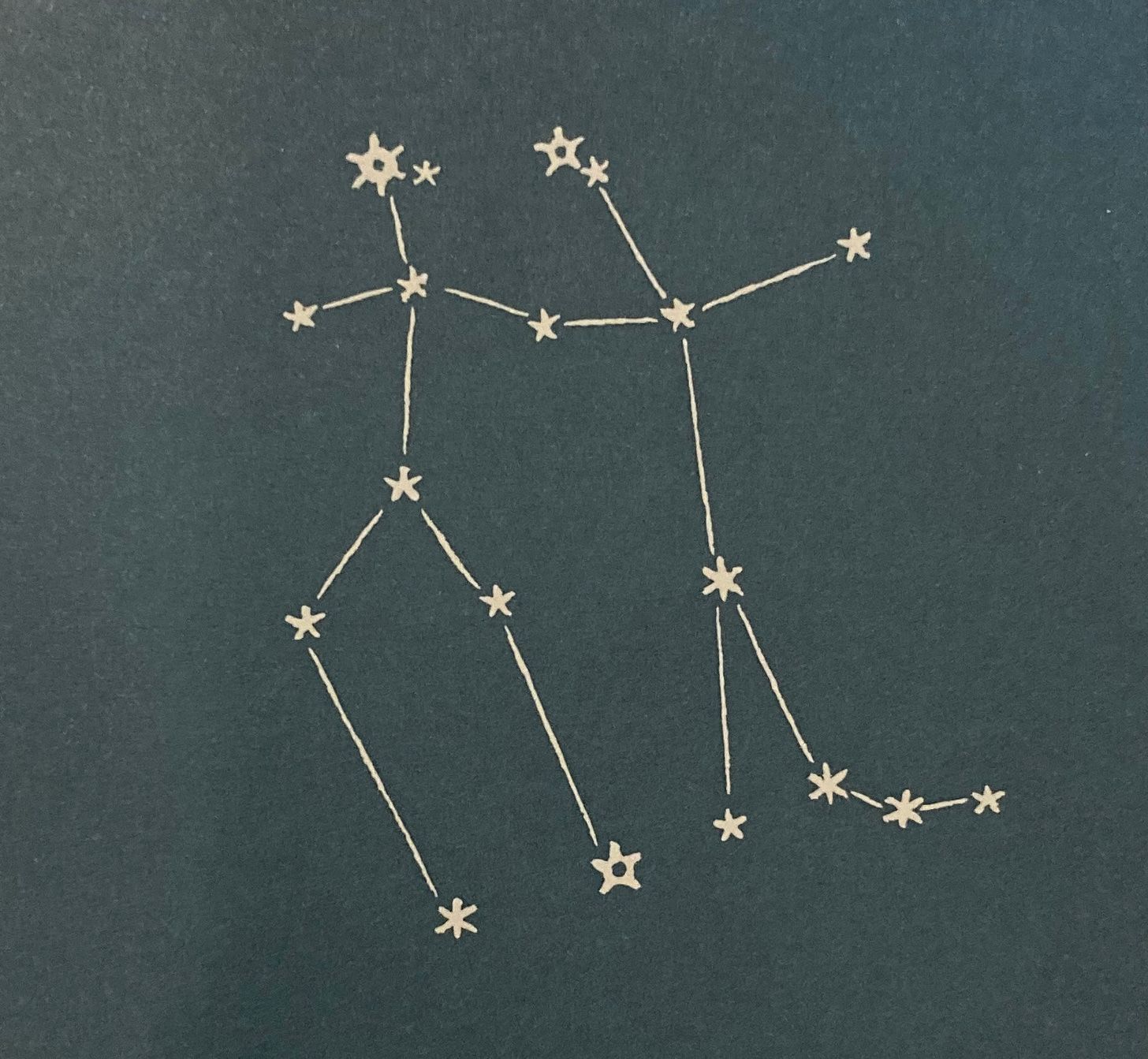

There are oodles of books that will teach you to do this; the only trouble is, they’re virtually all terrible. The lone exceptions that we know of are two by H. A. Rey: Find the Constellations (for kids) and The Stars: A New Way to See Them (for adults).4 His innovation is so simple it’s painful: instead of drawing frivolous pictures around the constellations that hide them —

or connecting the stars together randomly —

Rey takes the 🧙♂️METAPHORS seriously and plays “connect the dots” in a way that actually helps you see the constellation —

You may want to get both books at once; the second includes star charts that link up the constellations with the 🧙♂️SIMPLE STORIES they’re all characters in, making them even easier to remember. (For a delightful example of this, see our pattern Star Lore°.)

Practice E: The directions of nature

Finally, you can help your kids navigate outside in the daytime or nighttime when Sun and stars are nowhere to be seen. All it takes is to help them unravel some of Mother Nature’s directional clues. The master teacher of this may be Tristan Gooley, whom the BBC has dubbed “the Sherlock Holmes of Nature”, and whose best book for this is The Natural Navigator: The Rediscovered Art of Letting Nature Be Your Guide. And what he teaches is eye opening.

We all know, for example, that moss grows on the north side of trees. The only trouble is, much of the time, it doesn’t. It’s a fine clue, but no one clue will consistently point you in the right direction. If you want to confidently find your way in the woods, you need to weigh many of them together. The happy thing is, these work almost wherever you are in the Northern Hemisphere, where there’s one constant: the Sun shines directly from the south. From this, many things fall out:

on a hill’s south face, the grass will dry faster, and the flowers will bloom earlier

on a tree’s south branches, more leaves will grow

on the base of a tree’s south-facing trunk, the dirt will be drier, lighter, and potentially cracked

These are just a few; you can help your kids learn many, many more! The deeper purpose of this, of course, is that it’s a way to connect the small picture to the big picture, the close-at-hand to the extraordinarily far away. It’s an invitation to pay absurdly close attention to the world around you. (For more on this, look forward to our “Science” wireframe, coming soon.)

Forwards, upwards, and twirling towards freedom

Geography, done right, teaches children not just where things are, but that the world is real, and worth knowing.

All the above practices, of course, just lay the foundation of what we’ll be building in middle school and high school. To see that, stay tuned for our next wireframe. In the meantime, please fill the comments with anything you don’t understand, think we’re missing, or know we can improve on.

© 2026 losttools.org. CC BY 4.0.

Though you can probably make one better than that.

This one is organized by biome, rather than by continent/country, so it’s a bit harder to use for our purposes. I’ve figured out a little trick for making it more easily searchable; let me know if you’re interested, and I’ll put it in the comments.

And now if you’re realizing that the ball-ness of the planet actually screws with the cardinal directions, you’re right! Look forward to playing with that in middle school.

H. A. Rey also happens to be the man who created Curious George. And that is your trivia fact of the day!

This is great!

My five-year-old got really into coloring, so I bought a big poster-sized world map with the country borders drawn on it. It’s all white so he can color in all of the countries. Every day or so, whenever he feels like it, I let him color in a few countries as long as he can remember every country that he’s already colored in. It’s been a really good activity and now he can identify over 50 countries. Here are some observations I’ve made so far:

- He really likes it. Maybe that is just because he is a bit of a geography nerd like his father, but he has shown the map to some of his friends and they always seem really into it as well. A lot of their fascination comes from how big and small some countries are, especially the ones they’ve heard about.

- I have another world map that he uses as a placemat for his breakfast. He pays a lot more attention to it now that he can locate the countries that he’s colored in.

-Countries that he has heard about seem easier for him to remember. We live in a place with a lot of expats so he has had a fair bit of international exposure that may have piqued his interest in this whole project.

-In some ways it seems like the teaching is on autopilot. He’s picked up on concepts like continents and landlocked countries just by observing and asking questions.

-In other ways, things can be difficult to explain. For example, when he sees another world map that uses a different projection (e.g. Mercator vs. Robinson), he’ll point out “mistakes” in the new map. Perhaps what you wrote about orientation and navigation will be useful for tackling these sorts of problems.

Hi @Brandon Hendrickson,

Thanks for your article. It is excellent. Simple but powerful.

Many parents and educators do not realize the importance of teaching younger students Geography alongside History.

We humans love to learn from stories anchored in a specific place. It helps us empathize with the characters and believe that we, too, can overcome difficulties and challenges.