A fossil hunt to end the culture war

Preparing kids to fight beautifully across the political divide

There are a very few injunctions in the human art of rationality that have no if’s, and’s, but’s, or escape clauses. This is one of them: bad argument gets counterargument. Does not get bullet. Never. Never ever never for ever.

How can we stay in conversation across deep divides?

This, for reasons too obvious to mention, is a question on many of our minds.

One answer is that we should focus on the things that unite us, and steer away from our disagreements. I assume the ubiquity of this answer means that it must work for some people, but whenever I hear it I think of what the famed entomologist E. O. Wilson said when he learned about communism:

Great idea. Wrong species.

Which is just to point out that we’re monkeys; there’s something in us that will always stir us to fight when we meet people whose ideas we despise. This isn’t cause to despair! This is fine: we can use this inclination to fight differently — fight with our words and minds.

When we do this well, we don’t just avoid violence — we’re actually brought closer with the very people we disagree with. And when we do this very well, both sides are brought closer to truth.

It’s essential that we get this right in education. Alessandro and I are talking about how to build this into schooling at the earliest ages and at the most fundamental levels. If you’ve read my pattern Philosophy Everywhere°, you might not be surprised to hear that we’re calling it “Disagreements Everywhere”.

We’ll present more about that in time. For the moment, I’d like to preview a project that I’ll be doing through Science is WEIRD in the coming year, tentatively titled “Fossil in the Wrong Place”. It’s our small attempt to address the illiberal attitudes that are wrecking through society.

Presenting… “Fossil in the Wrong Place”

In the 2025–26 school year, Science is WEIRD is going to help young-Earth creationists prove evolution wrong.

Imaginary Interlocutor: I spot a typo in that last sentence. It sounded like you said you’ll try to help prove evolution wrong.

No typo! That’s exactly what we’ll be doing — not, I hasten to say, inside our weekly lessons, but around them. And we’ll be inviting our subscribing families (and the rest of the internet) to join in the fun.

I.I.: Aha! I’d heard rumors that you’re a flat-Earther; are you a young-Earth creationist, too?

I’m not! What I am, however, is a believer in engaging all sorts of ideas — even ones far outside the mainstream — because this is how science and philosophy actually work. Heck, it’s how the entire academy works. The engine that drives modern society’s brain is something like

find people to disagree with,

ask for evidence, and

stay in conversation with them.

Or, at least, it’s supposed to be — any of us can point to situations it’s been breaking down.

In Year 1 of Science is WEIRD’s big course, we focused on a funny, fringe question: are the flat-Earthers right? That’s why I had that frequently-delightful conversation with famous Flat Earther Mark Sargent.

That was just a warm-up. In years to come, we’ll be tackling some much weightier scientific questions around the environment:

is organic farming good? (Year 4 microbiology)

how promising are solar & wind power? (Year 4 physics, Year 6 Earth science)

how safe is nuclear energy? (Year 5 physics)

I.I.: Those are questions worthy of a science class. Young-Earth creationism, not so much.

I disagree completely. Somewhere between 10 and 40% of Americans believe in young-Earth creationism; I don’t know of any studies worldwide, but imagine them to be somewhere in that ballpark.

Young-Earth creationism — defined here as the belief that the universe is only a few thousand years old — is the default belief of many, many, many people. For us, at least, it’s a nice middle-step between engaging Flat Earthism and pressing environmental decisions that some very smart cookies disagree furiously over.

I.I.: Are you sure you’re not secretly a young-Earth creationist?

Oh, I’m very much not — but I used to be. I’ve written a little about this in the last section of my ACX book review, but the tl;dr is that it was becoming a young-Earth creationist that actually got me to see the power of the scientific process.

When I was a teenager on the internet, I became convinced by the some of the arguments for the standard young-Earth position: that the planet was less than 10,000 years old, that humans lived alongside dinosaurs, and that the fossils we find were animals killed in a worldwide flood.

I.I.: Were you an atypically dumb teen?

Not atypically, at least! But I was unusually curious, willing to follow evidence wherever it led, and unfamiliar with what bad arguments looked like.

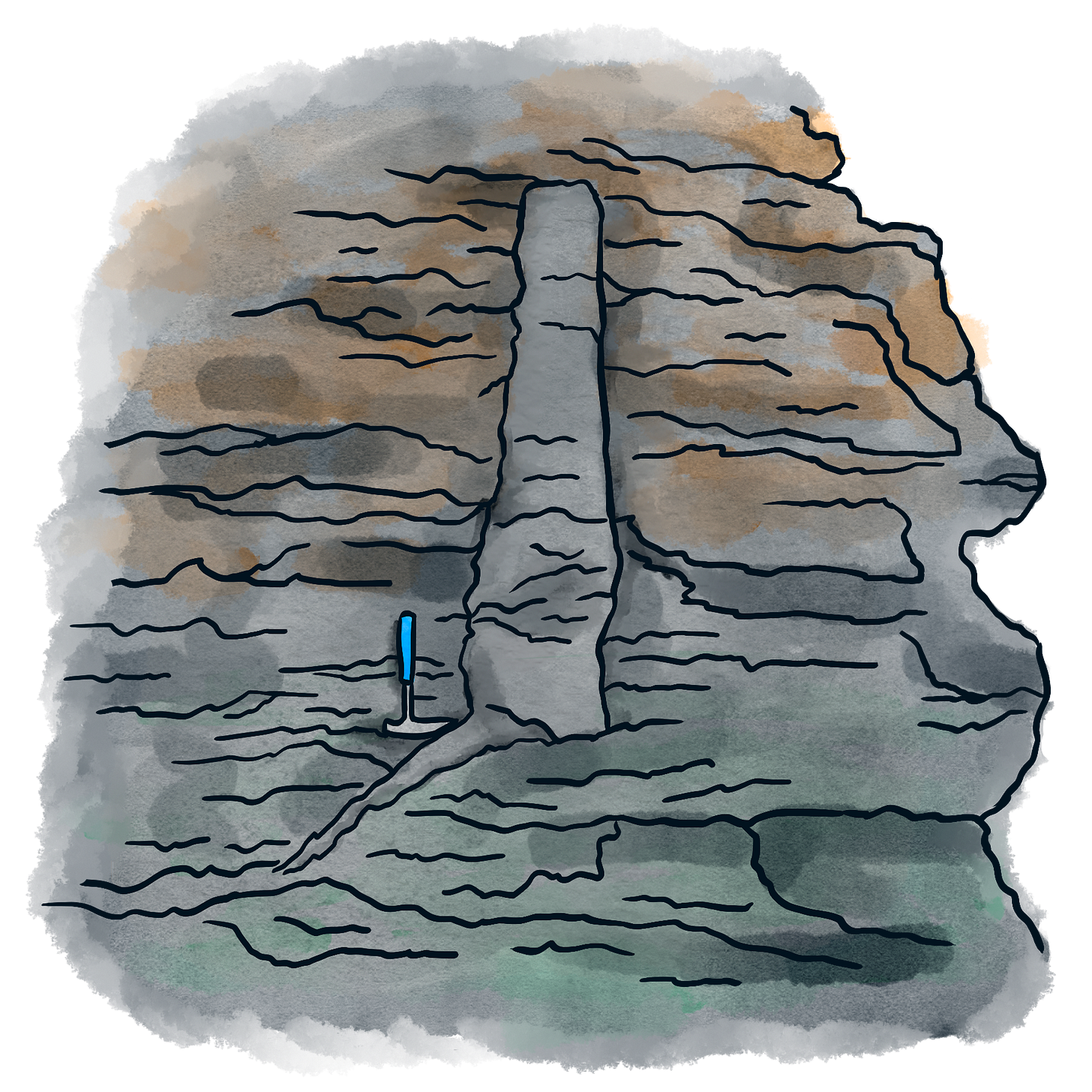

And some of the evidences certainly seemed compelling. My favorite is still “polystrate trees”: tree fossils that cut through many different layers of sedimentary rock.

If the layers of rock were really formed over millions of years, young-Earth creationists ask, then how could this tree have stayed upright? If mainstream science is correct, how could this fossil exist?

I.I.: …okay, now I’m a little curious myself.

Right?! I’ll leave it to you to look up mainstream geological explanations online. Note as you go, however, that most of them are terribly written: filled with abstruse geological terminology and high-level abstractions. I’ve found that this is common when mainstream scientists engage with people on the periphery.

As part of this project, I’ll be trying to communicate a clear and compelling explanation of what’s going on with this tree. For the moment I’ll only note that this debate is educational gold. It’s anomalies like this that catch our interest. And, indeed, this mirrors how science has worked for centuries: many of our biggest discoveries have come with people arguing across huge chasms staring together at weird details.

Wanna talk to people on the other side of a huge divide? Don’t ignore the chasm. Acknowledge it, and talk about it.

I.I.: Sure, but why “help young-Earth creationists prove evolution wrong”?

To be clear: I don’t think the mainstream scientific story of evolution over billions of years is wrong. The story is the culmination of many lifetimes of work by many brainy people all over the world, each trying to find things that the previous iteration of the story couldn’t quite explain. To the best of my understanding, it’s withstood every attack aimed it — and I know that because I used to be one of the people attacking it!

But, look, I might be wrong. As a good Bayesian, I don’t think that my confidence in anything can ever achieve 100%. I think that the odds of the evolutionary story being correct are high — certainly above 99% — but they’re not infinitely high.

And if I am wrong… well, I’d like to know that! Frankly, I’d love to find that out. I’ve been hugely wrong about desperately important things in the past. Whenever it happens, it hurts — but after that, it feels great. My repeated experiences of overturning beliefs has made me an intellectual thrill-seeker. Honestly, one of my worries is that, in the years remaining to me, I won’t uncover any more huge things that I’m wrong about.

So part of me would love it if were discovered that the whole evolutionary story is wrong. And if anyone’s going to do that, it’s likely to be evolution’s critics.

I.I.: But are you secretly trying to convert them to your beliefs?

Oh, it’d be unethical to do this secretly. It’s always a thrill when I get to help someone change their mind — it’s just that I’m inviting them to do the same to me. I’m always irritated when someone asks “but you’re not trying to convert people, are you?” in a tone that implies it’s bad to try to change people’s minds about something. Of course I am! Of course they are, too! Why else would we be talking to each other?

But of course it’s hard to gain trust across big divides. People assume you’re just trying to fight them, and don’t come with an open mind. Offering to help evolution’s critics prove evolution wrong is one way to flip the script, to over-advertise that you’re committing to staying open-minded, and to encourage similar behavior on the other side.

It’s not the only way to do it, of course. But right now we’re not exactly suffering from a surplus of ways to speak over our cultural & political divides. This is one way of doing it. It’s an experiment. I’m hopeful that it’ll bear fruit for how we create our Egan-powered K–12 curriculum and how we help kids in Science is WEIRD understand the actual scientific process. I’m also hoping it inspires other folks’ attempts to talk across divides.

I.I.: I’m pacified for the moment. Now: what are you actually going to do?

Lemme lay out the basics. And I’m posting this here before formally announcing it to my Science is WEIRD audience because I’d love to get your thoughts on how this could be done even more wonderfully.

There are two aspects: the contests, and the conversations.

The contests

We’re going to hold three contests across the 2025–26 school year. The first will be specific to anyone subscribing to Science is WEIRD, and will have a cash prize of at least $1,000. The other two will be open to anyone on the internet, and will each have a cash prize of at least $100.

Contest #1: Find a fossil in the wrong place

Educationally, the point of this contest is to show people that they don’t need to trust scientists blindly. In many cases, we can see for ourselves when an academic establishment is right or wrong. Sometimes, with a single inconvenient fact, we can upend much of mainstream belief.

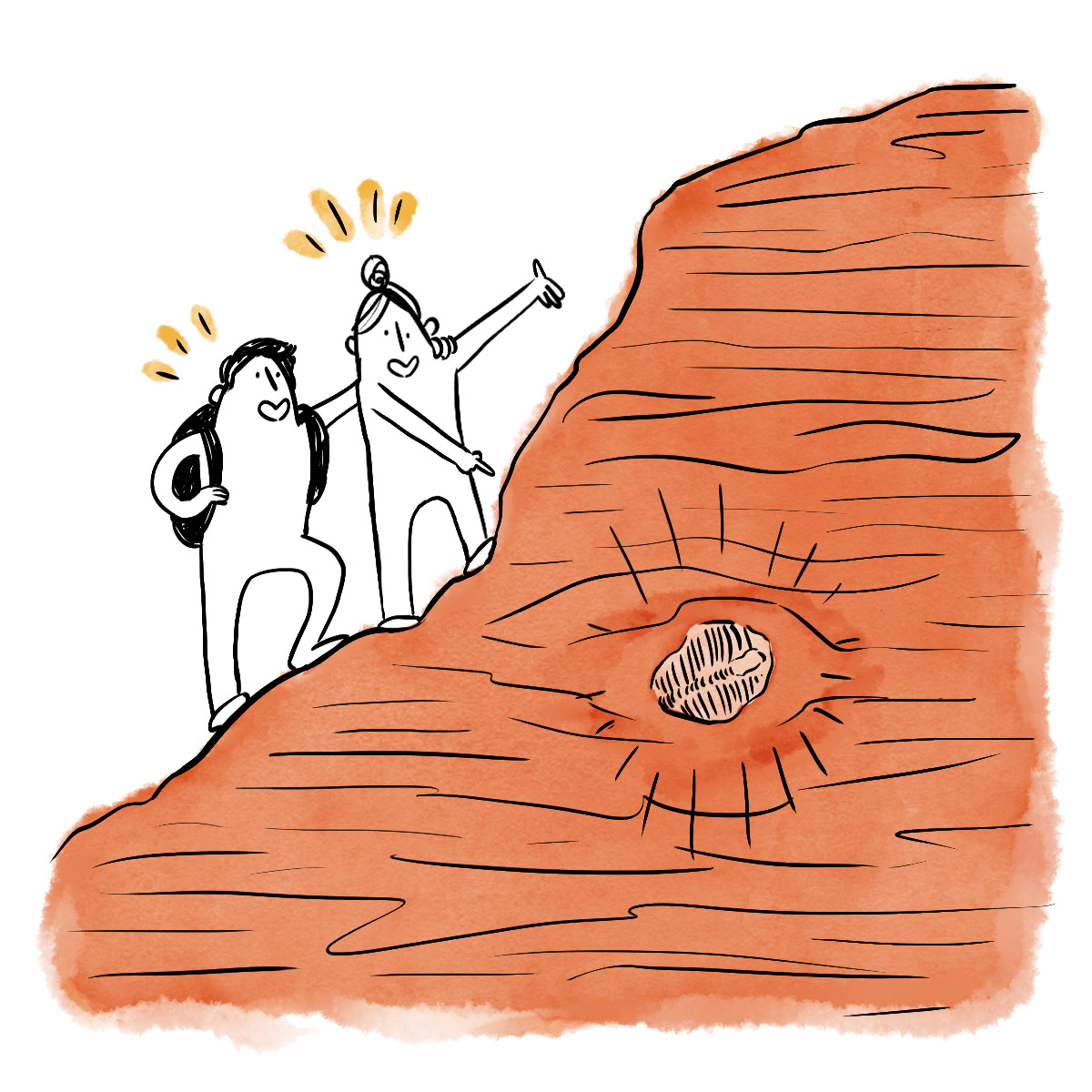

When I was a dinosaur-obsessed kid, fossil-hunting was opaque. Having no idea how to do it, I spent hours digging in the dirt next to our garage.1 But fossil-hunting is delightful, and you can do it nearly anywhere. So, throughout the 2025–26 school year, we’ll be showing kids how to find fossils where they live — where they should look, what they should pack, what they should pay attention to. Most of all, we’ll show them how to make sense of what they find.

At the end of the year, we’ll award some fun prizes — which fossil is the biggest, the best-preserved, the creepiest, and so on. But we’ll also be prepared to award a cash prize of $1,000 USD to anyone who finds a fossil in a layer of rock that mainstream scientists would be surprised to find it in.

According to most young-Earth creationists, they should be pretty easy to do. Most contemporary young-Earth creationism is based on a geological model called “flood geology”. It holds that the layers of rock come from one worldwide flood, described in Genesis, which killed nearly everything on Earth. All the sedimentary rock we see is the muck from the flood; all the fossils are the dead animals & plants.

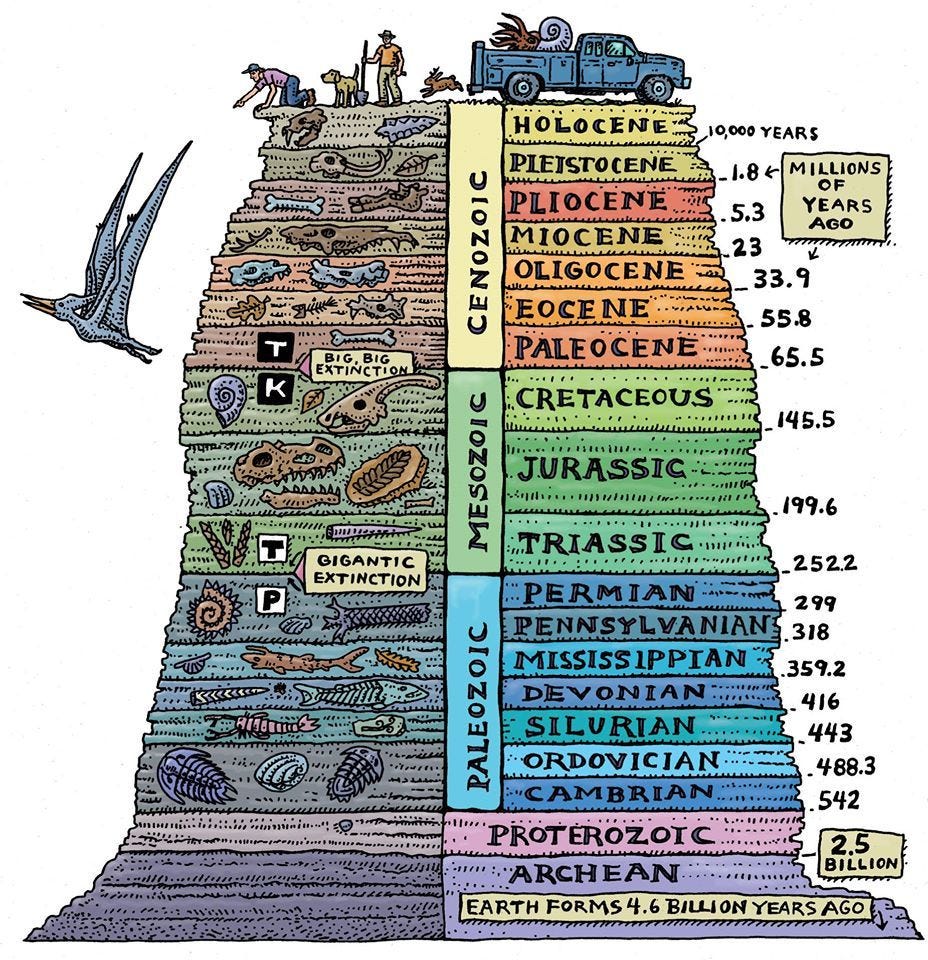

On the surface, this explanation seems able to explain some of the most important facts about fossils (like the fact that we find clam fossils on top of mountains). But it has one glaring weakness: according to it, the fossils we find should be jumbled up together, scattered throughout the layers. But that’s not how we find them at all: they come in the layers predicted by the mainstream evolutionary story:

When the biologist J. D. S. Haldane was asked to name something that would disprove the evolutionary story, he quipped “a rabbit in the Precambrian” — that is, a fossil of a mammal found in layer of rock that’s thought to have been formed before even fish evolved.

To win the contest, you don’t need to find a rabbit, specifically — you can find any fossil that’s in a layer that mainstream scientists would be surprised to find it in. And we’ll help you do it! We’ll help you identify your local layers of rock, and we’ll bring together a panel of judges to help you make sense of what you find.

If you can do this, we’ll award you $1,000, and will help you write up your discovery and submit it to academic journals of geology.

This contest will culminate in May 2026.

Contest #2: Make the best case for a worldwide flood

Educationally, the point of this contest is to show that it’s not enough to just talk with people you disagree with. To really engage, you need to respond to their very best evidence.

Well: what’s the best physical evidence for a worldwide flood?

Polystrate trees are just one of the many pieces of apparent evidence that flood geologists point to. But among these, which evidences are the most powerful?

Unlike contest #1, this contest will be open to anyone who can upload a video to YouTube Shorts. (That means it must be less than 3 minutes long; just tag it with #fossilinthewrongplace2.) Also, someone is guaranteed to win it! We’ll have a panel of judges evaluate the submissions, and choose the one that they conclude shows the most powerful evidence. They’ll decide at the end of November 2025, and the person with the winning video will get a prize of $100. And then I’ll make a response video to it in which I grapple with that evidence, and try to explain how mainstream geologists see that same evidence. You’ll be able to judge for yourself which side seems to have the better explanation.

Contest #3: Make the best model for a flood

Educationally, the point of this contest is to show that it’s not enough to poke holes in another’s theory. For your idea to win, it has to explain the evidence even better.

Well: which model of flood geology makes the best sense of the evidence that we see?

Young-Earth creationists understand that the layers of rock are a challenge for their theory. Admirably, many of them have constructed different models to make sense of why, for example, T. rex fossils are only found in the Cretaceous, while those scary Dunkleosteus fossils are only found in the Devonian.

Some of these models, frankly, sound weird — like the “floating forests” hypothesis, that proposes that before the Flood, animals lived on continent-sized floating mats of vegetation.

But that doesn’t mean that they’re not true, because science is weird! (Floating forests, frankly, have nothing on particle–wave duality.) The young-Earth creationist community should be bold in creating new ideas to make sense of the evidence. We’d love to help champion the best of them.

Like contest #2, this will be open to anyone who can upload a video to YouTube Shorts (use the tag #fossilinthewrongplace3). And also like it, someone is guaranteed to win it! Our judges’ll evaluate the submissions, and at the end of January 2026, choose the one that they conclude presents the most tenable model of how a worldwide flood could have put the fossils in the order we seem to find them. That person will get a prize of $100, and I’ll again make a response video to it.

The conversations

Throughout all this, I’ll be recording conversations with folk who have something interesting to say about this.

Hopefully, I’ll get to talk with paleontologists and geologists who can help us understand how to make sense of what kids are finding in the rocks. It’d be amazing to talk with philosophers and historians of science who can help us understand what the “secret sauce” of science actually is — and perhaps help us imagine how we can build it into a whole school’s curriculum.2 And I’d love to talk to psychologists and other folk who have insights into how to help people change their minds, and can give me advice on how to think more reasonably myself.

But above all, I want to be talking to thoughtful young-Earth creationists. Best-case scenario, we’re able to help each other shift our opinions. Worse-case scenario, I make a few more friends!

Educationally, the point of this is to show kids that the people on the other side of a chasm aren’t icky, and that disagreeing together can be delightful.

Questions and answers

Q: You say that you’re helping people “prove evolution wrong”, but I don’t hear you talking about biology. Why the fixation on geology?

In the future, I’d love to do a sequel to this focusing on natural selection, or help someone else pull it off. But this is already a big project; for it to be manageable, we need to focus it.

And, historically, these topics are related. The layers of fossils were a major inspiration for the idea of evolution. Darwin took Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology on his voyage around the world, and said it “made a profound impression on me”. Natural selection’s ability to explain why we find fossils where they are was also a major cause of why Darwin was so quickly embraced by fellow scientists.

Q: Do you actually think anyone’s going to find a “fossil in the wrong place”?

If enough people participate, yes! Again, if flood geologists are correct, then this will be easy. (Why people haven’t discovered this before will become a more interesting problem.) But even if the mainstream story is correct, there are still discoveries to be made. For example, T. rexes are thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, along with all the other non-bird dinosaurs. But it’s entirely possible that a handful of them survived on a little longer into the “age of mammals”3. If you know where to look, you might stumble on one of them! If so, you wouldn’t upset evolutionary theory… but you might make the cover of TIME magazine.

Q: I have no idea how to find a fossil, or how to tell if it’s “in the wrong place”.

We’ll help you with that. (For the moment, though, check out the website rockd.org, which will help you understand how long ago your local layers of rock are thought to have been laid down.)

Q: Why will the first contest — the actual fossil-finding one — be limited to families in Science is WEIRD?

One can fake a fossil, and it’ll take time and work for our judges to confirm the fossil is real. At least for this iteration of the contest, we need to put a cap on the amount of effort we put into that.

Q: Do I need to be a young-Earth creationist to compete in these contests?

Not at all! You can participate whatever your beliefs. (Not to over-quote Yudkowsky, but in the same post as the one above, he writes “If you feel that contradicting someone else who makes a flawed nice claim in favor of evolution would be giving aid and comfort to the creationists… then the affective death spiral has gone supercritical.” Which is to say, you should beware of tribal feelings around creationism. Participating in these contests might be good medicine.)

Q: $100 isn’t that big of a prize.

We’re not that rich of a company! If you’d like to help us make this a big deal, and would like to donate some money for any of the prizes, just ping me on Substack.

Q: I’m signed up for Science is WEIRD, and I have absolutely no interest in any of this.

Don’t worry — this whole project will mostly sit outside the lessons themselves, and will only come into focus when we do “Hills are Weird” (my personal favorite topic) in January 2026.

Q: Who’s on this panel of judges?

The selection is still underway! Ideally, we’d have three geologists or paleontologists: one a young-Earth creationist, one an old-Earth creationist, and one a mainstream scientist. If one of these describes you, ping me on Substack explaining your interest and your credentials.

Q: None of those describes me, but I have other skills that I think I might contribute to this discussion.

Ping me!

Q: I don’t have “skills” so much as “opinions”.

The comments section is open; help me crap-check this. (Again, that’s why I’m posting this here before I announce it in Science is WEIRD.)

Looking back as a parent, this must have been adorable. Mom, Dad, why didn’t you take pictures?!

For fellow philosophy-of-science nerds, contest #1 is Popperian, contest #3 is Kuhnian, and contest #2 is inspired by Michael Strevens’ The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science.

Did I just describe the plot of The Land Before Time 2?

Great idea for a project!

This sounds wonderful!

I was wondering how you plan to make it feel like a real, lively debate, given that to many people the question might seem like “settled science.” Right now it reads a little bit like schoolwork (which isn’t a bad thing!) rather than having the irresistible pull of an online disagreement. Will you be introducing the competitions in your usual lesson style, even though they’re outside the normal curriculum? I’d love to see how you bring the topic alive and get kids to really care about it.

And I’m interested in your reasoning behind letting kids only take the “wrong” side of the debate — I’m sure you’ve already thought this through, and I’d be keen to heard more about what you hope they’ll get from it!