Geography in middle & high school

Or: How to make reality take root

Table of Contents

Previously, in geography:

Part 1: Why geography?

Part 2: How’s geography done now?

Part 3: What geography can look like in grade school

And now, the thrilling conclusion…

Part 4: Geography in middle school

Part 5: Geography in high school

Part 6: Geography in preschool/kindergarten

In our last wireframe, I suggested that a rich elementary geography curriculum might be seen as a rope of three threads:

Maps

Marvels

Navigation

As kids get older, these threads continue, but evolve.

4: Geography in middle school

In these four years, we want to master the techniques to tame our alien, exotic, and fascinating reality. Starting especially in 5th grade, we can take full advantage of the tools of ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) understanding.

I.I.: Can I have a little review on these “Ways of Understanding”?

We’re building our elementary curriculums on Kieran Egan’s conception of MYTHIC (🧙♂️) understanding. In my review of The Educated Mind, I suggested that the simplest way to understand the tools of Mythic understanding is “the things that kids are already good at” — things like 🧙♂️STORIES, 🧙♂️JOKES, 🧙♂️MENTAL IMAGES, 🧙♂️ROLE-PLAYING, 🧙♂️REVERIE, 🧙♂️RHYTHM, 🧙♂️METAPHORS, and 🧙♂️EMOTIONAL BINARIES.

We never really put away those tools, but as we grow into adolescence, we’re often drawn to new tools — like 🦹♂️IDEALISM, 🦹♂️EXTREMES, 🦹♂️HEROES, 🦹♂️GOSSIP, and 🦹♂️HOBBIES/COLLECTIONS. In fact, as I pointed out in the review, we often become obsessed with these. These are the tools of ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) understanding, and we can use them to power this quest to get the world into kids’ heads.

MS Geography Thread 1: Maps

Practice A: Make a big, personal map of the world

Through these four years, our kids have one goal: be able to draw, from scratch, a map of the world.

Make this a big deal.

I.I.: What’s the point of drawing a map when professional ones already exist?

Drawing is a way to see what’s inside your own head… and we want to fit so much into kids’ heads.

The drawing event itself should be ritualized, held on a special day at the end of each year (grades 5, 6, 7, and 8), and given a couple hours at least. The drawings should be as accurate and as beautiful as the kids are able to make them, and show off their own (increasingly personal!) understandings of the world.

Practice B: Regularly draw maps

In elementary school, we matched names to the shapes on a map. But the shapes themselves are important; to get them in our heads, we need to practice drawing them. So: practice for the year-end draw-the-whole-world events by regularly learning how to draw different parts of the world.

I.I.: This sounds hard! How do you recommend doing it?

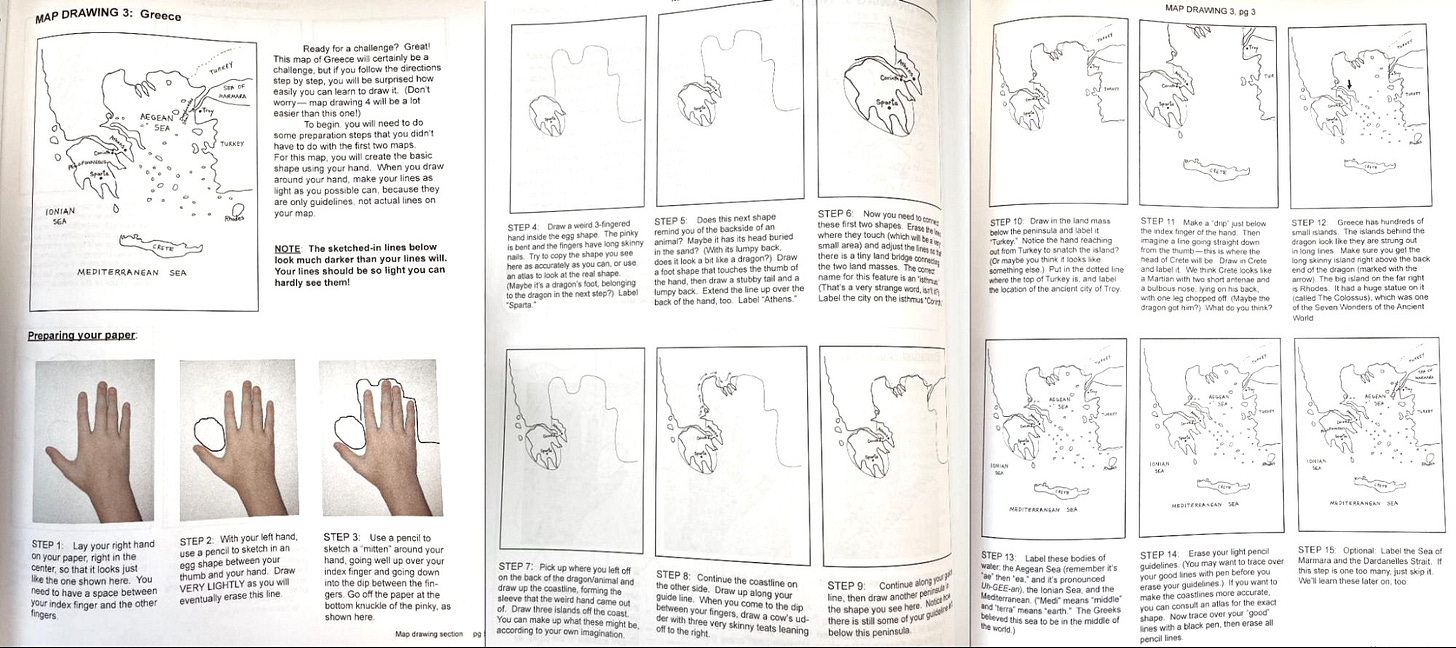

Thank goodness for the nerdiness of the homeschooling community! There are a few books that have already tackled this problem. My favorite is Ellen Johnston’s Mapping the World with Art, which makes ample use of 🧙♂️METAPHORS to remember the shapes:

I.I.: How long would it take to go through this?

The book has 88 pages of instructions. Assuming a 30-week school year —

88 pages ÷ 4 pages a day = 22 weeks ≈ 1 year

88 pages ÷ 1 page a day = 88 weeks ≈ 3 years

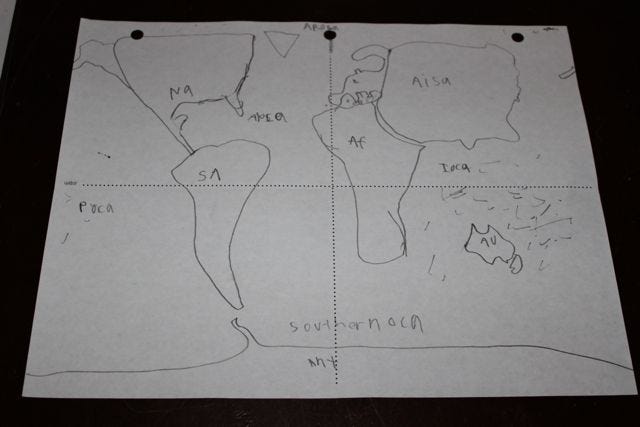

The book’s downside is that it doesn’t address drawing the whole world until the end; we, however, want to start with it — the whole gives meaning to the parts! Here, we can lean on a method that Leigh Bortins advocates in The Core: Teaching Your Child the Foundations of Classical Education.1 In short: divide a paper into four quadrants (the equator and the prime meridian), and then draw blobs:

I.I.: That seems hard.

Bortins wisely emphasizes the blob part. Start with crudely-drawn ovals — your first task is just to get the right number of continent-thingies in their right places. (North America in the top-left, Asia in the top-right, Australia in the bottom-right, and everything else straddling the lines.) After that, it’s just fine-tuning! (Fun fact: there’s a profound error in the map above, bespeaking a fundamental misunderstanding of all the continents. Try to guess it in the comments.)

I.I.: Do you just expect kids to get better through repetition?

No, of course not. To get better quickly, we need a component of deliberate practice — immediate feedback:

draw a place

compare it with a professional map

make corrections with colored pencils

Step 4 (not shown here) is to immediately draw the place again, and see if you got better. (You’ll also benefit from drawing all these maps in a special notebook, which’ll allow you to quickly see your progress over time.)

Practice C: Learn all the major countries, rivers, deserts, seas…

In elementary school, we learned a bunch of places in higgledy-piggledy through “Marvels”. Now, we’ll memorize them systematically: the world’s biggest deserts, the largest mountain ranges, the longest rivers, all the ~195 countries, and so forth.

I.I.: Gosh, why suck all the fun out of things?

Actually, the urge to make complete collections is a fairly common feature of adolescents. (Egan notes that it’s so obvious to people outside of education that it’s long been commercialized by any number of trading card companies. It’s also enshrined in the Pokémon song: gotta catch ‘em all!)

I.I.: What order should these be learned in?

At some point, we’ll find a crack curriculum maker to work with and devise a sage path through this madness. In the meantime, you can DIY this by compromising and putting the most important stuff first.

Here’s a stab at it:

I.I.: Where do those links take me?

To an enchanted fragment of the pre-internet world called “Seterra”.

Seterra is a geography quiz app. It was created in Sweden by the programmer Marianne Wartoft as a personal project to make a simple, fun way to learn world maps and flags. Over the decades it grew from floppy disks into a globally-used website with customizable exercises used by millions of users around the world. It was sold to GeoGuessr a few years ago.

It’s so, so good.

I.I.: Any tips on how to use Seterra?

Since it was purchased by GeoGuessr, Seterra’s free web version is now choked with ads. It’s definitely worth paying a few bucks to get a subscription. Or, better yet, download the iPad or Android versions: it’s much more fun to use your fingers, and they’re either cheap or free.

If anyone is interested in advanced tips for using Seterra better, lemme know in the comments; I’ll share some there, or spend a bit of time making a special paid-subscribers-only post about it.

National geography should be brought into this. Here’s a stab at America’s:

I.I.: All of this is easier said than done. How do you propose to make this easy?

Before you practice where a place is, it’s nice to know that it is. Singing some 🧙♂️SONGS — and really one song in particular — can help kids preview the places, and learn to pronounce them. My fellow English-speaking 80’s kids probably know about “Yakko’s World”:

…but did you know there’s a cottage industry of YouTube videos that update it, and fix its problems? (For instance, “Caribbean” was never a country. YouTube is your friend in finding these; here’s a good 2025 version to start with.)

You could, of course, try to memorize the song, but the low-hanging fruit is

just being able to sing along to it while looking at the lyrics, and

being able to point to the countries on a map at the same time.

(It should be noted, too, that Yakko’s scouse-speaking brother Wakko has a parallel song for the 50 U.S. states.)

Practice D: Collect strange maps

Put up the oddest maps you can find on your walls.

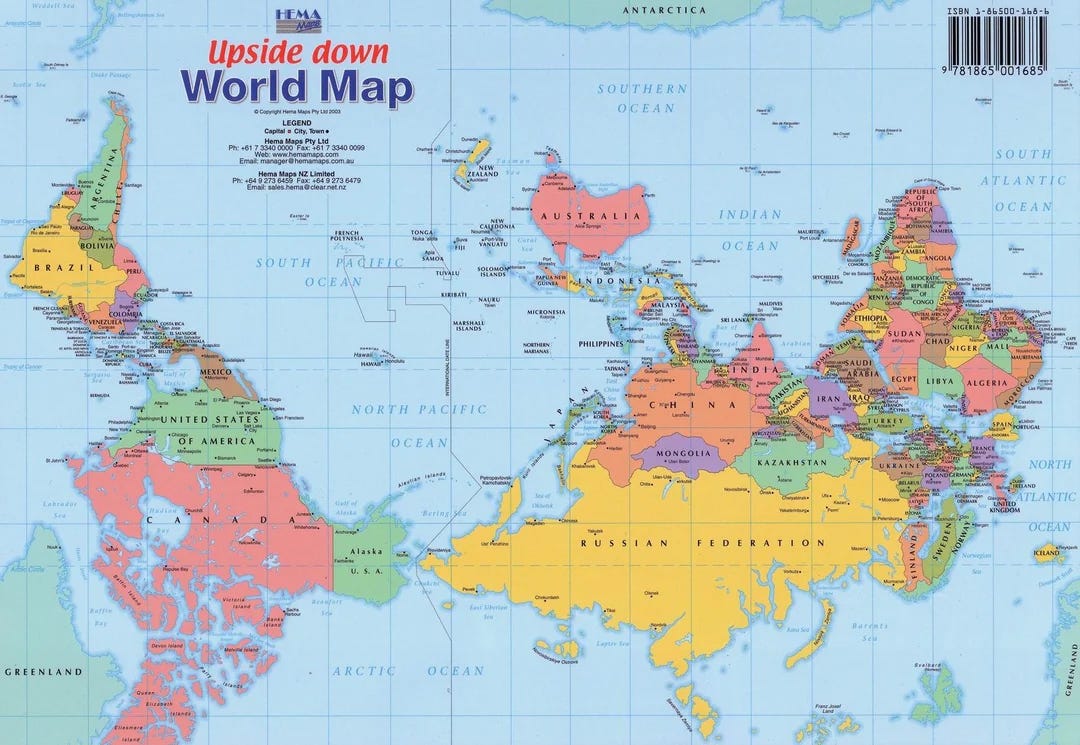

As we’ll be discussing below, every map lies. The solution is to have more maps: different projections, different orientations, different data… you name it.

A note on ages

In the years to come, we want to be starting whole schools that follow these wireframes, and for that, we need some order for which practices start when. If you're doing these yourself, feel free to ignore this, and do what works best for your kids!MS Geography Thread 2: Marvels

In elementary school, we let our choice of marvels be idiosyncratic. Now, we’re going to use marvels to help us achieve a more systematic grasp of the place of the world, and of the limits of Earth itself.

Practice A: One marvel for each hard-to-remember place

When something in Seterra just isn’t sticking in your head, find a marvel about it, and make a memory card for that. Watch as the hardest places to memorize become the easiest. You can use these for hard-to-remember nations, capitals, mountain ranges, rivers, deserts, and so on.

A great place to find these are the Atlas Obscura books I waxed eloquent on in the last wireframe.

Practice B: A marvel for each extreme

Create a sort of Guinness Book of World Records for geography, done as memory cards.

Egan writes that, as kids grow up, their sense of the world sharpens, and moves from fantasy to reality. We start off hearing fables about mountains so tall they pierce the clouds… but do such mountains really exist? Teens naturally are drawn to 🦹♂️EXTREMES; this helps them get a grasp of the nature of reality.

Taking this seriously, we can make memory cards for some very simple questions:

what’s the hottest place in the world?

what’s the coldest?

what’s the highest mountain peak?

what’s the deepest ocean trench?

which place is the windiest?

which place is the calmest?

what’s the densest city?

what’s the emptiest region?

what’s the most massive volcano?

which country has the most murders, and which has the least?

which major city is the most dangerous, and which is the safest?

which nation is the richest, and which is the poorest?

which nations are moving the most quickly from the one to the other?

How many of those do you feel like you probably know the answer to — and which would you most like to know? (Feel free to do the hive-mind thing in the comments.)

MS Geography Thread 3: Navigation

Practice A: Globe directions

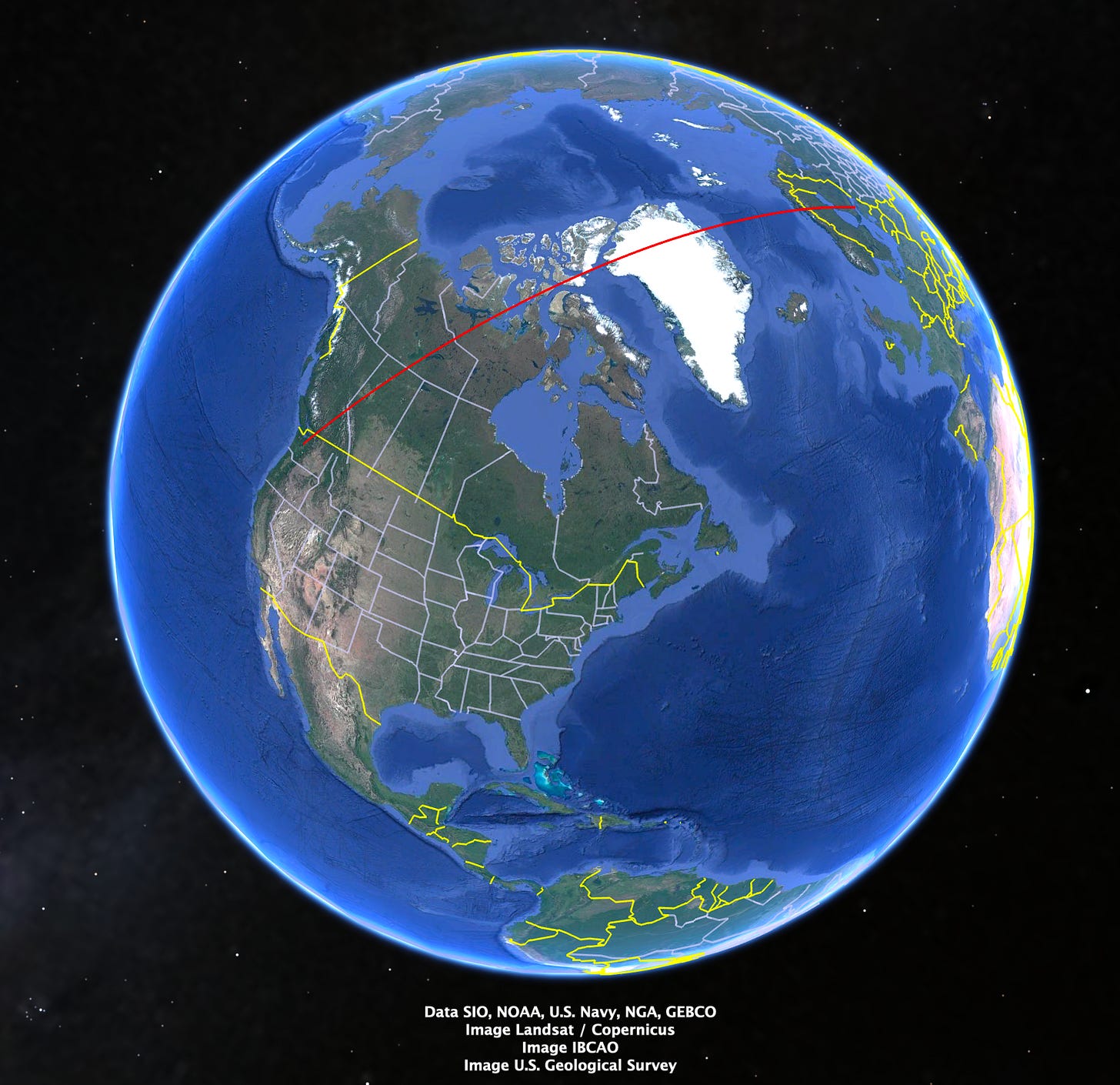

In elementary school, we internalized the cardinal directions. The only trouble is that east and west, in fact, aren’t directions! So in middle school, start using the actual directions to the places you’re talking about. This is hard, because your brain is a flat-Earther.

I.I.: Come again?

We all “know” the Earth is round. But we use flat maps so often that they warp our sense of where things are.

Say you live in Seattle, face directly east, and fire a gun. Pretend it’s a very powerful gun — the bullet flies so fast it doesn’t fall to the ground but keeps going around it.2 Pretend, too, that the bullet miraculously doesn’t hit any U.S. people or buildings. What’s the next country it’ll fly over?

The answer is so unexpected that I’ll put the link to it at the end of this post so you’re not tempted to ruin it too hastily. But here’s a simpler puzzle as a hint: If you live in Seattle, is Helsinki to the east or to the west?

The correct answer is that it’s nearly straight north:

Our minds aren’t used to imagining living on a globe! And the more that one becomes a “map-head” (to use the charming phrase by Ken Jennings in his excellent book of that name), the more one risks ironing a wrong view of the world into our brains.

I.I.: How do we do that?

You could do a lot of math… or you could just stretch a piece of thread between two points on a globe (your town and the place you’re talking about), and eyeball it.

Practice B: Guess the distance

In elementary school, we focused on direction, but ignored distance. So: when you’re learning a marvel (be it the Taj Mahal or your local ice cream store), guess how far it is away.

This is a way to develop the power of the Philosophic tool 👩🔬QUANTIFYING EVERYTHING.3 At first, though, you might build that up by using units based on🤸♀️MOVEMENT. Ask how long might it take you to run, drive, or fly to the place? Then you can compute back to distances:

you run about 6 mph | 10 kph

you drive about 60 mph | 100 kph

you fly about 600 mph | 1,000 kph

So a two-hour run would mean ~12 miles away, and so on.

Practice C: Moon o’clock

In elementary school, we learned to tell time by staring directly at the Sun; did you know that you can do the same thing with the Moon?

I raised this possibility in the pattern Track the Sky°, though I didn’t have the time to flesh it out there. I don’t here either, though I can give some hints:

where is the Moon in the sky? (it rises in the east and sets in the west)

which part of the Moon is lit up?

With these, you can figure out where the Sun is, and the Sun’s location is how we set our hours. (If you’d like to understand more, watch the YouTube video I Learned to Tell Time by the Moon. Here’s Why It Was Hard.)

Practice D: Orienteering

In elementary school, we learned to tell north and south by reading nature’s signs. The more systematized sequel to this might be geocaching, and the thrill-seeking sequel to that might be orienteering.

Geocaching is treasure-hunting. You’re provided a set of GPS coordinates at which a box sits, and you have to figure out a route to it.

Orienteering is a Scandinavian invention that combines equal parts of jogging, map-reading, and not panicking. It developed in the late 1800s as a way to train Swedish soldiers; it’s since escaped into public life, and for the last century has been used in schools around Europe.

Look for more on these when we give the wireframe for our physical education curriculum. (If you have any experiences in either geocaching or orienteering, feel free to share them in the comments.)

5: Geography in high school

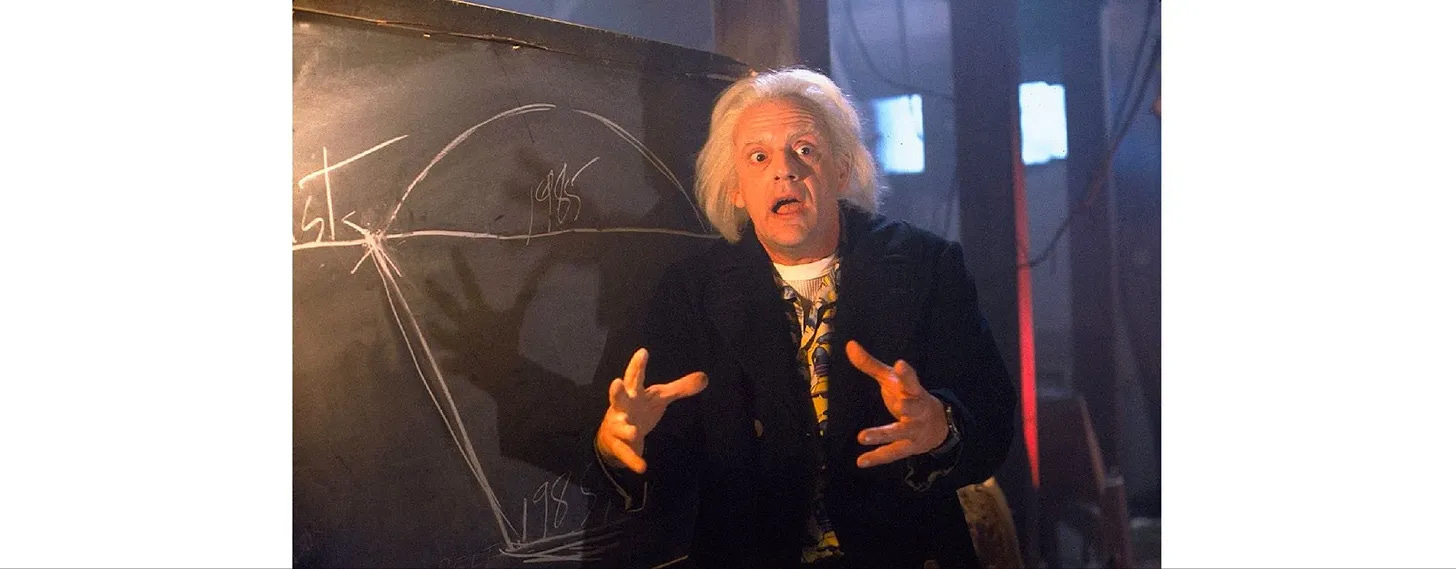

In high school, we want to help students knit together a detailed, coherent, realistic model of the world. As we go through these four years, we can lean increasingly on the tools of PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding.

I.I.: Remind me, once again, what “Philosophic” understanding looks like.

In my book review, I suggested a heuristic for calling to mind the tools of Philosophic understanding: ask what motivates mad scientists?

They ask 👩🔬BIG QUESTIONS, float 👩🔬CRAZY IDEAS, and build 👩🔬GENERAL SCHEMES which they use to seek 👩🔬CERTAINTY and find 👩🔬THEIR PLACE IN THE COSMOS. Then they point out 👩🔬ANOMALIES in each other’s schemes, get into 👩🔬IDEA FIGHTS. To win, they tend to 👩🔬QUANTIFY EVERYTHING.

These are the tools of PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding, and they’re what fuels modern intellectual life.4

A note on high school:

If we're doing our job, these practices will seem too good to be true.

That's because, with the exception of some elite academic high schools, the things we're suggesting can't be done in most schools, because the students aren't ready for them.

In an important way, few contemporary students are actually "students", at least in the original sense of that word, which was meant to connote "zeal" and "pressing forward" to understand something. (This is why I tend to avoid the word when describing people in elementary and middle school.)

But if we pull off our middle school curriculum —— if we regularly help kids become "map heads" —— we think they'll not just be able to do the following practices, but be hungry to do them.HS Geography Thread 1: Maps

Practice A: Debates in cartography

So… what do professional map-makers get into fights about?

I.I.: I actually imagine them as fairly dull people.

If you counterfeit a lanyard and pop into a cartography convention, you might be surprised.

even if we all hate the name “Gulf of America”,5 is there actually a principled reason to prefer one name over another?

how should the ownership of a place like Kashmir, which is claimed by both India and Pakistan, be shown on a map?

is the Mercator projection racist?

is there a north-hemisphere bias to putting the North Pole on “top”? Should half of all maps be drawn with the Arctic on the bottom?

Here, I’m limiting myself to fights over maps themselves — I’ll save some of the questions of geography more broadly for our History wireframes.

Practice B: The math of maps

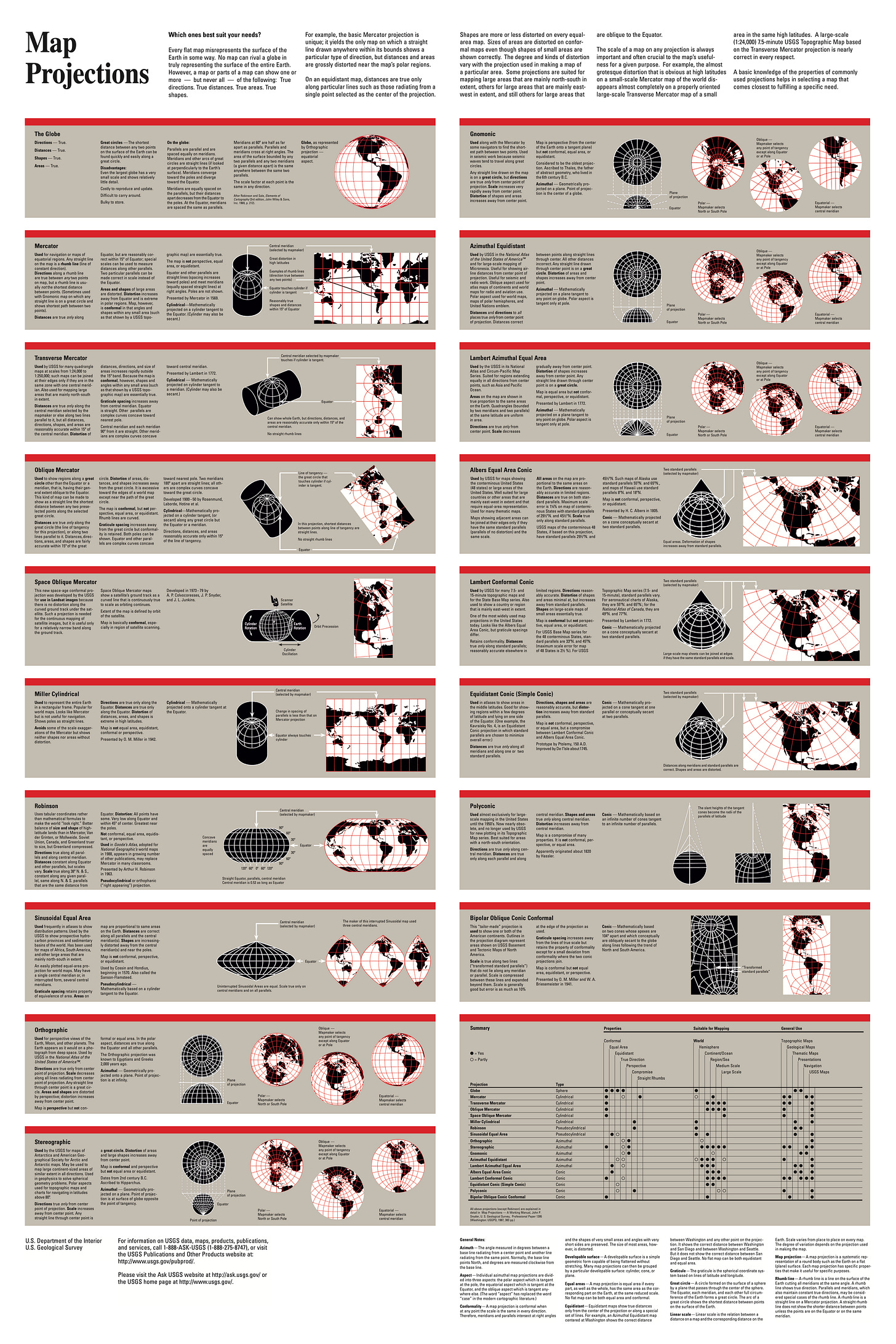

Having become map geeks, with strong opinions on different projections, we’ll now dip our toes in the water of understanding how different projections actually work.

I.I.: Do you mean actually crunching the numbers?

What an aspiration! With a gifted teacher, perhaps. But (as professional mathematicians love to remind us) math needn’t always involve numbers. A handful of diagrams can illustrate a big idea of cartography quite succinctly: all maps lie.

There is no neutral projection of a globe onto a flat plane; in order to do it, you have to distort something profound. There’s no getting around this: it formally falls out of Carl Friedrich Gauss’s “Remarkable Theorem” of 1827. The only choice we have is what distortions we want to live with… an idea that actually peeks into IRONIC (😏) understanding.

HS Geography Thread 2: Marvels

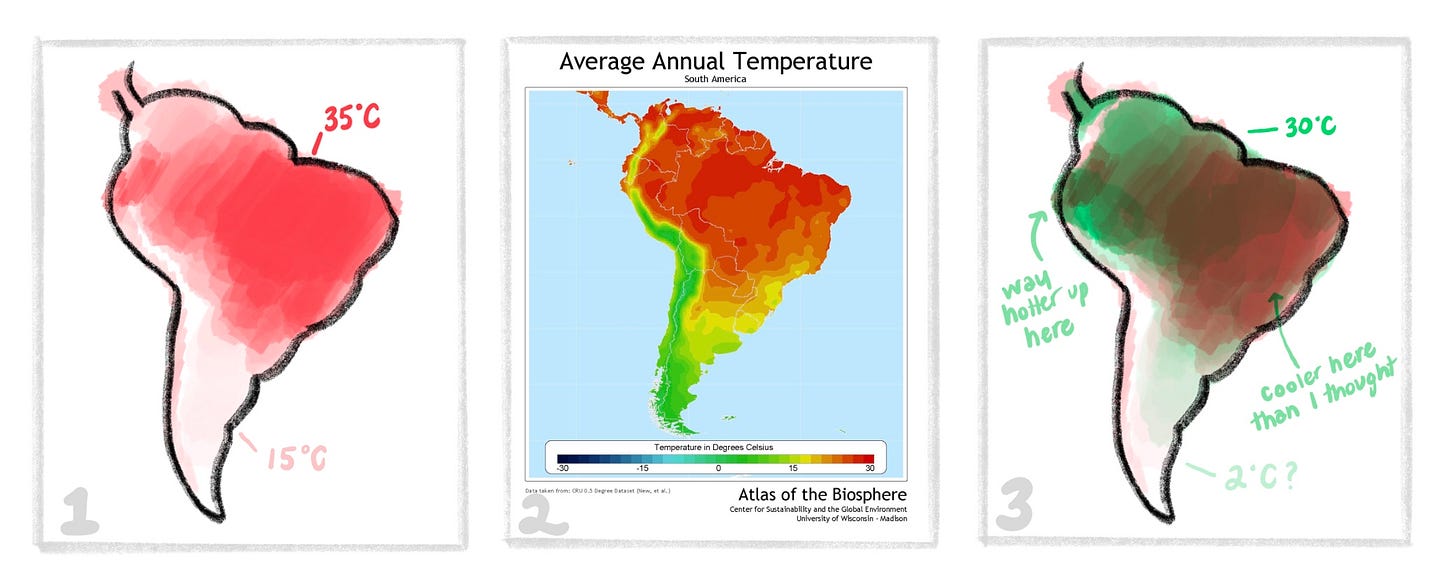

Practice A: Shading maps

In middle school, we focused on shiny, bright specifics, and incidentally learned a lot about different countries. Now, our attention turns to systematizing that knowledge into building 👩🔬GENERAL SCHEMES.

Pick an interesting quantity that varies by location — say, for example,

population density

crime

average temperature

infant mortality

wealth

most common religion

age

…and with a colored pencil, shade in how you think it varies.

Check a professional map.

In a different color, shade over your first draft with the real amounts.

Cartographers call these “heat maps” or “density maps”.6 This is an utterly simple practice, but out of it can come major intellectual growth, because it corrects our internal model of the world.

Practice B: Correlations

On a map, shade two quantities (each in a different color), and observe how they interact.

How does population density overlap with crime? How does wealth overlap with CO2 emissions? How does the birth rate overlap with literacy?

Again, do a 1–2–3. Here:

Shade in both guesses.

Consult professional maps of each.

Reflect, in writing and conversation, about where your guess was right, where it was wrong, and what might actually be driving the correlations you see.

Practice C: Where in the World?

Give kids a photo of some random spot in the world. Only using details in the photo, how close can they get to figuring out where the photo was taken?

This is such a great idea that you see it all over the place. The political writer Andrew Sullivan runs a weekly “View from Your Window” contest with reader-submitted entries which are really hard.

GeoGuessr (the company that purchased Seterra) runs a slick gamified version, with different levels of difficulty. Becoming great at any of these requires having a truly insane amount of knowledge of the world (to get a sense of how much, check out Scott Alexander’s post on training an AI to do this).

HS Geography Thread 3: Navigation

Practice A: Plan a route

The ultimate reason to know the map of the world is to be able to do things in it. So, pick a place, and figure out how you might get there. First create a model in your mind, then check the internet to see how correct you were. Kick it up a notch by estimating time and cost. Kick it up again by min-maxing different variables.

For example: can you tell me how you could get to Niagara Falls?

You first guess at an answer. This requires reflecting on your model of the world. (“I could fly there, but that would first require driving to the airport. Then I’d need to rent a car at one of the NYC airports and drive to the falls… wait, that’s on the US/Canada border. There’s gotta be a big Canadian city that’s closer to it. Which city might that be…?”) You could then check your guess against reality by doing some Googling.

At a more advanced stage, you could then estimate how long the trip might take. (“It takes me only 20 minutes to drive to my small local airfield, but do they have flights that go to NYC? If not, it’s 90 minutes to the big airport. I think a plane flies at about 600 mph, and I think Niagara Falls is about 600 miles away, so the flight itself would only take about an hour. But then I’d need to drive that rental car the rest of the way…”)

Then estimate the costs. (“A 20 minute Lyft might just be… ten bucks? How much is a plane ticket to NYC? And then how much would the other car ride cost?”)

At a very advanced stage, you can try to min-max different values by playing with some odd situations:

what if I have a million dollars, and really want to get there fast?

what if I only have a hundred bucks, but a month?

what if I’m trying to do this with the smallest carbon footprint, but have all year?7

As a fun twist, you can do this based on certain values:

what if I care most about speed, and money were no object?

what if I’m trying to save as much money as I can, and have forever to get there?

what if I’m trying to do this with the smallest carbon footprint — would it be better to ride a horse, or take a boat?

For locations, you can start with the “Marvels” you’ve already learned about… but could also do it for random latitudes & longitudes, and even random historical periods.

Practice B: Astronomical navigation

Learn to see where you are on Earth by looking at the night sky.

In elementary and middle school, we learned to estimate time with the Sun and Moon, but if you know the time and date, you can also figure out where you are on the Earth — or at least your latitude. It’s most accurate to do this with the stars.

Doing this puts students in the imaginative role of early explorers. It’s a way to grasp the roots of knowledge.

Practice C: How fast are you going?

Practice seeing how fast you’re going when you’re sitting down.

It doesn’t look like you’re moving, but motion is relative: the Earth is (of course) spinning on its axis, which means you’re moving around the Earth. Anyone at the equator is going ~1,000 mph, but what speed are you going at your latitude?

At the same time, the Earth is also falling around the Sun at nearly 70,000 mph. In the daytime, do those speeds add together, or subtract from each other?

And at the same time, the Sun is also falling around the Milky Way at about 500,000 mph. How does that interact with the other speeds?

This requires students to hold a 3D model of our local branch of the Universe in their heads. (I can imagine doing this as a race to see who can go the farthest in one second: the winner will be whoever can most accurately hold these vectors in their head, and relate them to the room.)

5: Geography in preschool/kindergarten

I.I.: Seems odd to save this for last!

We want to lay out everything that we’ll be reaching for in our geography curriculum (and the others to follow) before sketching a sense of how we might pave the way before elementary school. Without that, we risk falling into “cute things for kids to do”.

While Alessandro and I have both taught young kids before, neither of us is a trained preschool or kindergarten teacher, so our thoughts here are incomplete: we’d love your ideas in the comments.

To pave the way for “Maps” (Thread 1), we think it a great idea to bedeck your home in maps! You can find ones that focus on topics your particular kids find interesting — animals, say, or dinosaurs. When someone mentions another part of the world, you might want to raise your eyebrows, say “I wonder where that might be…” and walk over to the map. Every once in a while, turn one of the maps on your wall upside down, and ask if that makes it wrong. And be on the lookout for buying the biggest, spinniest globe you can find on your local Craigslist.

To pave the way for “Marvels” (Thread 2), go to marvelous places! When you’re there, invest time in 🧙♂️REVERIE and commune with something special. (We’ll have much more to say about this in our “Science” wireframe.)

To pave the way for “Navigation” (Thread 3), look for stories and movies of explorers. Pretend you’re a pirate, and practice your swashbuckling on the bed. Create a treasure hunt: stuff an old kitchen spoon in the bushes, and write a few clues that lead to it. And this goes without saying, but get out and explore.

Thus ends geography

Last time, I wrote:

Geography, done right, teaches people not just where things are, but that the world is real, and worth knowing.

I think we can improve on that now.

Geography, done right, is an antidote to drift. It saves us from thinking of the world as an abstract idea-space mediated by screens; it’s a single real object with shape, weight, and distances. Adults who have drawn the world, sung about it, and navigated it don’t float so easily into the fantasies the infest the 21st century. This is what we mean by “making reality take root”: geography needn’t sit on the surface of the mind as mere facts. It can grow deeply, and help everything that students learn matter.

If this way of teaching geography feels like it is itself worth rooting in the world, you’re invited to help it grow.

If you’d like to, you could share this with one particular person who might appreciate these ideas (a social studies teacher? a homeschooler? just a geeky parent?). Or you could post this to a group of such weirdos (but, um, don’t lead with that). And if you know of any podcasters or journalists who’d be interested in this approach, that’s a powerful way to get more people working with these ideas.

Also, you can write a comment with any ideas or questions you have:

are you less than 100% sure you know what something in here means?

do you feel like we’re missing something?

does something seem weird or off?

The answer to the bullet puzzle:

The answer can be found on the Twitter thread by Fin Moorhouse that I adapted the puzzle from; h/t to Scott Alexander.

© 2026 losttools.org. CC BY 4.0

I’ve had some critical things to say about that book, but this is the author at her best — plucky and original.

A tad less than 20,000 mph — about the same speed the International Space Station orbits the Earth.

This will be a major focus of our high school curriculum, for my fullest treatment of it so far, see our pattern Masters of Measurement°.

Well, these, and spite.

And some of us really, really hate it.

Or possibly “isopleth” or “choropleth” maps? I’ll admit that I’ve spent quite a while trying to figure out the differences between these categories, and keep coming up confused. If anyone would like to set us straight in the comments, go for it.

I think that for me, this would involve buying a derelict rowboat in Duluth and eating fish I catch along the way; put your guesses in the comments.

One problem I notice with the blobby map is that it puts boundary lines where there aren't any real physical boundaries (Europe/Asia, Central/South America).

Interested in seterra tips! Our challenge with it has been that because we can't review the things we get wrong more frequently than the things we're solid on, it takes a while! I've been debating just switching over to the ultimate geography anki deck for the efficiency of spaced repetition.