History in elementary school

Or: How to turn the past into a place

Table of Contents

Part 1: Why history?

Part 2: How’s history done now?

Part 3: A new approach to elementary history

1: Why history?

Our big fat hairy problem

Congratulations! You’re a human in the 21st century — you’ve won the vertebrate lottery!

Now what?

By every biological measure, we’ve succeeded. No other animal has ever lived with more power or comfort. We live to see the majority of our kids survive us. Evolutionarily, this is what winning was supposed to look like. So why don’t we feel like it? As E. O. Wilson put it:

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. We thrash about. We are terribly confused by the mere fact of our existence, and a danger to ourselves and to the rest of life.”

We worry that none of what we do matters. We retreat into doomerism, suicide, or egoistic pleasure-seeking.

What history can do for us

A fully-humanized history curriculum can help us explore what it can mean to be human. It can help us gain vision for both ourselves and our societies.

I.I.: This is where you unveil to kids the secret meaning of life?

Oh, would that we knew that! We don’t have any one precise answer to “what humans can be”. The question has been answered many times, by people from different times, cultures, psychologies, and life trajectories, sometimes in radically different ways.

What a good history curriculum can do is help us explore those.

I.I.: That sounds like a pretty heavy responsibility for a history curriculum to shoulder.

You’re right. The task of helping students be more human is shared by all the disciplines… but history has a special role to play. As I’ll never tire of citing Susan Wise Bauer:

“History is not a subject; history is the subject.”

History is the glue that binds the bigger meanings of the curriculum together. When kids hear in math class about Eratosthenes’ (successful!) attempt to measure the Earth from the length of a shadow, his story will mean more because they’ll already know stories from Greece in the 3rd century BCE. Ditto with all the origin stories we share — rather than taking place in some undefined “a long time ago…”, kids will be able to place the stories in the bigger story of humanity.

2: How’s history done now?

How progressivists do history

How does Poppy the Progressivist approach history? By asking what’s most relevant to kids’ needs.

I.I.: But how can history even be relevant? It’s definitionally “things that are not happening”.

And in fact it shouldn’t be shocking that, over the last century, educational progressivists have made history just one small feature of social studies.1

But most progressivists still want some history taught. So how can it be relevant?

Poppy might explain how she focuses on skills rather than content. There are far too many details for anyone to ever learn; meanwhile, a skill like “historical thinking” will be useful across your life. How do professional historians read documents? How do they use evidence to argue? How do they connect the present and the past?

How traditionalists do history

Things look very different on the other side. How does Theresa the Traditionalist approach history? By asking what’s most important to developing a historian. And to Theresa, the answer to that is simple —

So what information, secured in a kid’s brain, will best prepare them to understand the most history later?

The answer for this, traditionally, has been names, dates, and facts:

When did King John sign the Magna Carta? 1215.

When did Columbus land in the Americas? 1492.

When did Japan bomb Pearl Harbor? December 7, 1941.

In fact, in some traditionalist classrooms, this seems to be nearly all of what history is.2

And now, back to us

From an Egan perspective, both progressivists and traditionalists have some good insights into what history can be. The only trouble is that, save for the intervention of a gifted teacher, both sorts of history teaching often end up dead. Egan never tired of citing studies showing that in elementary school, social studies was the least-liked subject. And does anyone dispute the emptiness of the classical history curriculum — not in its ideals, but as most people experience it? Traditionalists should appreciate the irony that the greatest argument against their work was done in opera:

We need to make history come alive — to pull together kids’ emotions, hopes, and clear-headed thinking.

Easier said than done, obviously. How can this be pulled off?

3: What history can look like (in elementary school)

History is made up of at least two threads:

the one BIG PICTURE of everything that’s ever happened

a zillion different STORIES

Here I’ll unveil what Alessandro and I have been planning for these in elementary school. A warning: these practices are rather extreme. We think it’ll give educational progressivists & educational traditionalists quite a lot to love (or, worst-case scenario, an opportunity to gang up on something they both hate, which would be success of a different sort).

If we pull this off, though, we’ll secure the foundation of a more fully humanized history education than we’ve seen anyone else create.

Thread 1: 🧵History memory palace

We’re going to turn our homes/schools into memory palaces — sprawling collections of events on our walls, chronologically arranged, which will span the entire history of the Universe, and which will allow us to secure (and more deeply understand) everything that we learn.

This’ll take a couple days.

I.I.: Why not just make a timeline?

We’re on record as being big fans of timelines! (See Nested Timelines° for my particularly wonky take on them.) But they have a crucial weakness.

Their strength, of course, is that they externalize information. Because you can see more than you can hold in your head at once, this allows you to be historically brilliant… but only when you’re staring at a timeline.

Their weakness is that they don’t actually help you get the information to stay in your head.

Well, as we said in our very first geography practice, we want to get the world into kids’ heads; for that, we’re going to need something more powerful than a timeline. So we’re starting from a different place — in fact, the very science of place. As I wrote about in that post, location is neurologically special: vertebrates have special parts of our brains devoted to tracking where things are.3

The ancient Greeks figured out how to exploit this. Thus was born the Method of Loci (colloquially called “a memory palace”). In short, you pick a building that you know well, and you use its rooms & details as fixed locations where you deliberately place the things you want to remember.

We’ve written a bit about this before in our pattern Art of Memory°, but if you’d like step-by-step instructions for how to make and use a memory palace, I recommend this page at The Art of Memory.

(Note: this was first inspired by Ed Nevraumont’s post, “How to memorize all the presidents” [link!], which gives the most straightforward explanation of how to create a memory palace that I’ve ever seen. We’re doing this a bit differently, but you might enjoy reading his approach.)

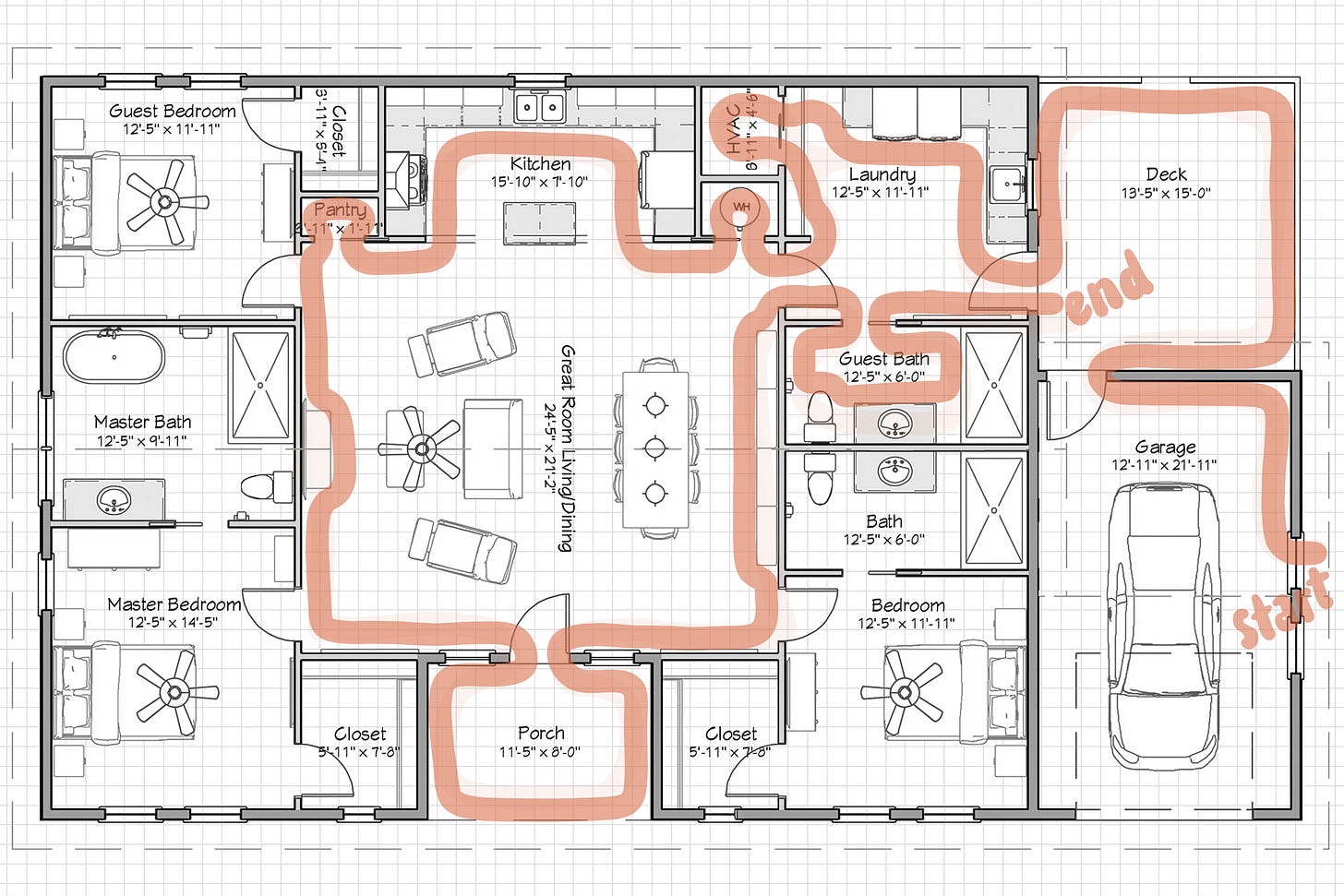

Practice A: Walk a path through your home/school

Chronological order matters, so in order to turn a building into a memory palace, you’re going to need to decide on one official path through it.

My recommendation is to pick a door and start with it. This will be where the Universe begins, so feel free to choose one with some metaphorical heft. (In the Hendrickson household, we’ve started in the garage, whose chill and darkness seem fitting.)

Then choose a direction — left or right. You’re going to follow this direction through your entire home/school. Touch the wall with one hand. Walk a path through your building.

Ideally, choose a path that doesn’t require you to back up. (This can mess with your sense of location.) The path, though, can be as twisted as you care to make it, and in a pinch you can imagine a portal connecting one part of your building with another.

At the end, you might want to exit out a different door.

Practice B: Pick 22 spaces

Now, you’re going to divide your path up into 22 “spaces”.

I.I.: What constitutes a “space”?

A “space” can be more-or-less any wide space of wall. The bigger, the better: a whole room would be ideal, but as most of us don’t have 22 rooms in our homes, we have to get creative. Smaller spaces include:

a closet

a shelf

a piano

a particularly large window

If you still don’t have enough, you can make some of the outdoor areas “spaces”, too.

These do need to be in areas, though, that everyone has access to. (My teenagers hate it when anyone comes into their rooms uninvited, and if you’re turning a school into a memory palace, you probably want to avoid individual classrooms.)

Practice C: Label the spaces

Each space is going to hold a particular span of history. Go ahead and create a little label, and hang it up near the space.

Space 1: Matter (13.7 billion years ago – ½ billion years ago)

Space 2: Life (538 – 251 million years ago)

Space 3: Life (251 million years ago – 10,000 BCE)Space 4: Prehistory (9,999 – 5,000 BCE)

Space 5: Prehistory (4,999 – 1,000 BCE)Space 6: Ancient (999 – 500 BCE)

Space 7: Ancient (499 BCE – 1 BCE)

Space 8: Ancient (1 CE – 499 CE)Space 9: Medieval (500 – 999 CE)

Space 10: Medieval (1000 – 1499 CE)Space 11: Early Modern (1500 – 1549)

Space 12: Early Modern (1550 – 1599)

Space 13: Early Modern (1600 – 1649)

Space 14: Early Modern (1650 – 1699)

Space 15: Early Modern (1700 – 1749)Space 16: Modern (1750 – 1799)

Space 17: Modern (1800 – 1849)

Space 18: Modern (1850 – 1899)

Space 19: Modern (1900 – 1949)

Space 20: Modern (1950 – 1999)

Space 21: Modern (2000 – 2049)

Space 22: Future (2050 – 2099)

I.I.: Do I need to write “BCE/CE”? Is that more historical than “BC/AD”?

Culture-war-adjacent fights about identically-useful-but-superficially-different systems may literally be the death of us. I literally flipped a coin for this; you do you.

Practice D: Add dots

To prepare the way for the second thread — “History stories” — we’re going to put five dots on each space. These can be small stickers, or pieces of tape.

Each dot is going to be where we’ll put one story.

I.I.: Do I really need to use stickers?

Masking tape would work okay. You want to put something there as placeholders for the stories we’re going to tell.

That said, color can be a powerful memory device. We bought these stickers to bedeck our home, and picked a different color for each “meta-story”:

🔴 red: space 1 (the story of matter)

🟠 orange: spaces 2 & 3 (the story of life)

🟡 yellow: spaces 4 & 5 (prehistory)

🟢 green: spaces 6–8 (ancient history)

🔵 blue: spaces 9 & 10 (medieval history)

🟣 purple: spaces 11–16 (early modern history)

🩷 magenta: 17–20 (modern history)

⚪ white: space 22 (the future)

I.I.: Anything else I should know?

For reasons that’ll become clear soon, spaces 2 & 3 should get six dots each. And as we’re currently living in the middle of space 21, make the first two dots magenta, and the last three dots white.

I.I.: Do I need to put these on the literal wall?

To keep the path easy to remember, keep things close to the wall, at least. Don’t make spots in the middle of a room. The floor is a bad choice, and couches aren’t much better. The drapes are okay.

I.I.: What do each of these dots represent?

They’re a span of time. We’re going to tell at least one story that takes place in each of these (see Thread 2 below). How much time they span, precisely, depends on what part of history we’re talking about.

In the history of the “early modern” and “modern” world, each dot holds just one decade. So, for example:

🟣 space 11, dot 1: 1500s

🟣 space 11, dot 2: 1510s

🟣 space 11, dot 3: 1520s

🟣 space 11, dot 4: 1530s

🟣 space 11, dot 5: 1540s

In the history of the “ancient” and “medieval” world, each dot holds a century. Thus:

🔵 space 9, dot 1: the first century

🔵 space 9, dot 2: 100 CE

🔵 space 9, dot 3: 200s CE

🔵 space 9, dot 4: 300s CE

🔵 space 9, dot 5: 400s CE

I.I.: Why do the old dots have bigger spans?

Less cool stuff happened then.4 And this expansion gets even more extreme the further back we go. In “prehistory”, every dot holds a millennium:

🟡 space 5, dot 1: 4000s BCE

🟡 space 5, dot 2: 3000s BCE

🟡 space 5, dot 3: 2000s BCE

🟡 space 5, dot 4: 1000s BCE

🟡 space 5, dot 5: first millennium BCE5

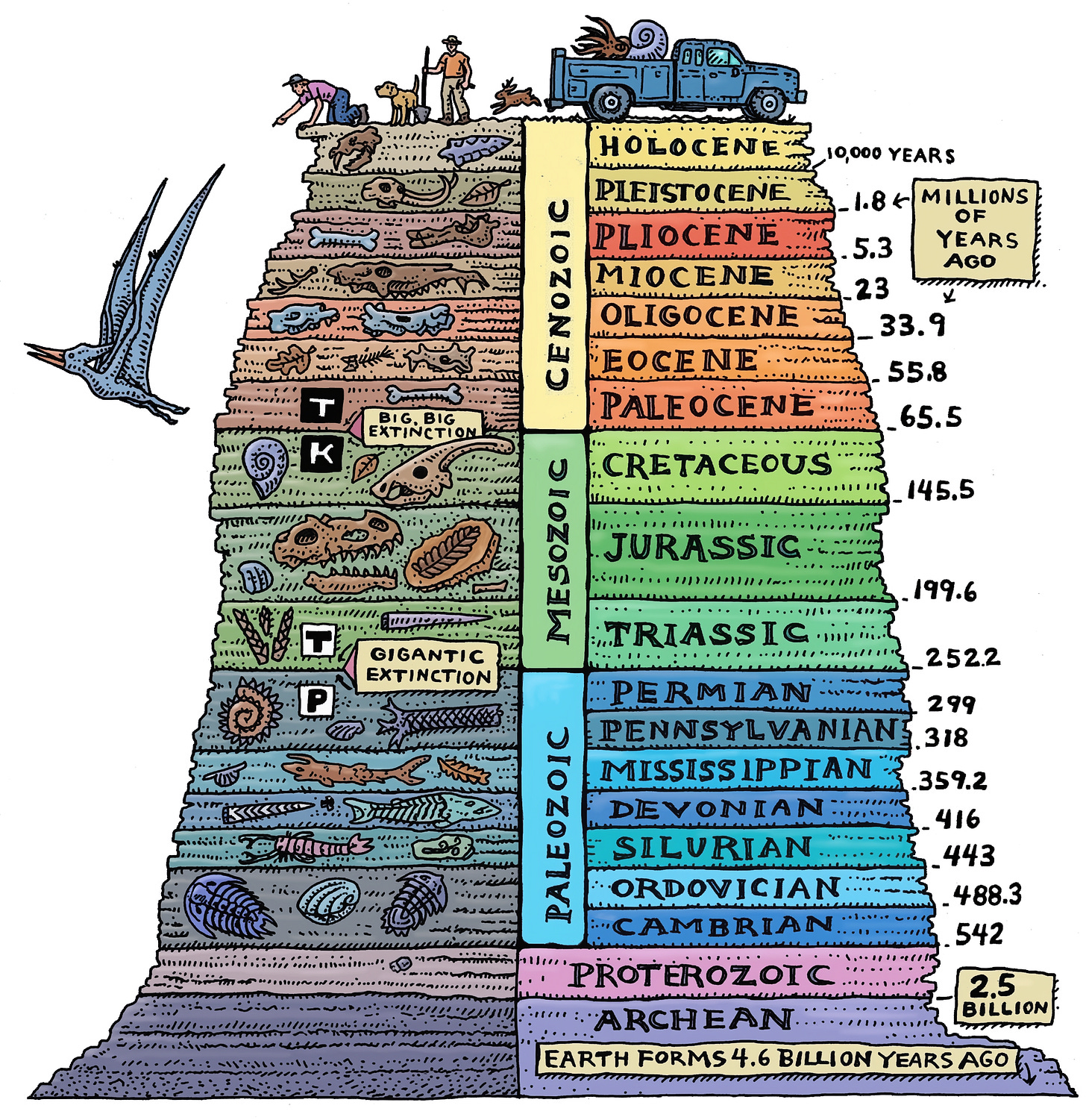

“Prehistory” in this breakdown, by the way, goes back to about 10,000 BCE — around the end of the last Ice Age. Before that are the two “Life” rooms that do stuff before humans evolved; to keep them graspable, we key them to geologic eras:

🟠 space 2, dot 1: Cambrian (542–488 million years ago)

🟠 space 2, dot 2: Ordovician (488–444 mya)

🟠 space 2, dot 3: Silurian (444–416 mya)

🟠 space 2, dot 4: Devonian (416–358 mya)

🟠 space 2, dot 5: Carboniferous (358–299 mya)

🟠 space 2, dot 6: Permian (299–252 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 1: Triassic (252–201 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 2: Jurassic (201–145 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 3: Cretaceous (145–66 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 4: Paleogene (66–23 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 5: Neogene (23–2.6 mya)

🟠 space 3, dot 6: Pleistocene (2.6 mya–10,000 BCE)6

And the very first room has a logic all its own:

🔴 space 1, dot 1: cosmic soup (0–0.4 million years after the Big Bang)

🔴 space 1, dot 2: first stars (0.4–200 million years)

🔴 space 1, dot 3: first galaxies (200 million–9 billion years)

🔴 space 1, dot 4: solar system (9–10 billion years)

🔴 space 1, dot 5: first microbes (10–13.3 billion years)

I.I.: Why are we going back all the way to the Big Bang? I thought this was history, and that’s a humanities thing.

In school, nearly all the time in “history” will be about humans (see “History stories” below). But we need a method to hold everything that we learn in school.

One goal of an Egan education is to help kids explore how we’re all fibers in the great 13.8-billion-year story of Life, the Universe, and Everything. This is the domain of the discipline of Big History, which we’re champions of — something we’ve written about before in our pattern Big History°.

I.I.: How many dots am I going to need?

22 spaces × 5 dots each + 2 extra = 112 dots

(Again, those two extra dots come in those “🟠 Life” spaces — the ones with the dinosaurs.)

I.I.: I understand that one “empties” a memory palace after they use it. Are we going to do that?

Memory palaces are emptied when they’re used for ephemeral information, like getting the groceries. It’s common practice, though, to keep them permanently for things like the elements of the periodic table. We’ll be following that course: our history events are going to keep growing and connecting as school progresses.

Speaking of which, it’s time to turn to the main course, for which the memory palace merely sets the table.

Thread 2: 🧵History stories

After setting up your memory palace, pick ~100 great, true stories from history, read them to our kids, and play inside them. After each, we’re going to put a little picture next to the dot on the wall.

At a rate of one story per week, this’ll take three or four years.

History is big. We have an embarrassment of riches: too many fascinating people, eras, and societies than anyone can learn. We need a trail of bread crumbs through it… and these stories can be that trail.

Practice A: Tell simple stories

I.I.: Why ~100? Weren’t there 122 spots precisely?

We’re going to choose at least one story for each dot in your memory palace — or at least the dots in the last 12,000 years, the ones that include humans. (We’re on the fence as to whether we’ll make stories for, say, squid and dinosaurs and such.)

I.I.: Cool cool. But which ~100 stories?

We’ve been working on a list for months, and in next week’s post, will be inviting your help! But “which history is most important?” is a monstrous question. In some ways, it’s the question of all questions — it can only be decisively answered once one fully understands, well, everything! The best we’ll ever be able to hope for is a Good Enough (TM) scope and sequence.

But right now, I can tell you some that we’ll almost certainly be using:

🟡 space 5, spot 3 (2000s BCE): the princess, priestess, and mathematician Enheduanna writes hymns to the goddess of love

🟢 space 7, spot 1 (400s BCE): Leonidas and his three hundred Spartans fight and fall at Thermopylae

🔵 space 9, spot 1 (500s CE): St. Benedict survives numerous assassination attempts by unruly monks to found the monasteries that will preserve the texts of the ancient world through the Dark Ages

🔵 space 10, spot 5 (1400s): Chinese eunuch Zheng He commands a huge fleet of treasure ships across the Indian Ocean

🟣 space 11, spot 4 (1530s): the Incan civil war between two brothers weakens the empire and opens the way for the Spanish conquest

This is to say that the stories should be fascinating, important, and serve as an entry into many cultures and sorts of people. (There are more criteria, but we’ll talk about these in the next post.)

How can we make these stories meaningful to everyone?

We narrativize them, of course!

In the geography posts, I treated the narrativizing process as an option to help kids who aren’t naturally geography Ravenclaws. In history, it’s more load-bearing. For each of these, I’ll use a story we’re considering for 🟢 space 7, spot 5: “Caesar and the Rubicon.”

Phase 1: Orient

Behold the hook! How can we create anticipation for the story to come?

One way is to ask a 👩🔬BIG QUESTION that pulls kids in:

what should matter more — following the law, or helping the people you love?

is it good to be prideful?

should you ever overthrow your leaders?

A second way to hook kids into the history story is to do a Touching the Art process on a painting about it — say, “Jules-César arrivé au Rubicon” by Gustave Boulanger:

(This isn’t the space to explain the Touching the Art process. Suffice to say right now, it’s the game-changing creation of the brilliant Luc Travers, who I’ve interviewed here, and we’ll be incorporating it into our art curriculum — stay tuned! In the meantime, you can purchase Luc’s book on it.)

It’s not particularly gripping, but this would also be a good moment to point to the location the story is going to take place on a map.

Phase 2: Complicate

Now, actually read the story aloud.

I.I.: That’s it? “Read it”?

There’s reading, and then there’s reading. You’ll want to pull out all the dramatic stops here. Emote. Give the characters different voices. Put your heart into it! (You might also want to sit on the floor, dim the lights, and put on some white noise.)

Also, we recommend making full use of one of the oldest tricks in the book — cliffhangers. Break the story into two or three parts, and read them over a couple days. Milk your kids’ desire to know what happens next. Use the pauses as opportunities to guess what’ll happen next.

Phase 3: Transform

In phase three, we want to make something with our kids. Here, the natural thing is to choose a way to play with the story and make it our own.

In elementary school, kids can 🤸♀️ACT OUT the story with their bodies, or pick stuffed animals to 🧙♂️ROLE-PLAY the characters. They can pick one crucial moment and 🤸♀️DRAW it, or even make a comic book of it. They can treat it as 🦹♂️SPECULATIVE FICTION, and by changing one tiny event, imagine how the rest of the story would play out. This is a small sampling — for more, see the pattern Playing inside Stories°.

Playing with the story, however, can also mean playing with its ideas. You can

Is Caesar a hero, or a villain? How could we find out?

How bad must a government get before you should risk a life (yours and/or others’) to overthrow it?

If someone says “I’m doing this for you?” how do you know whether they’re telling the truth — or if they’re just out to help themselves?

(Like the orientation question near the top, these pull from our Philosophy Everywhere° pattern.)

Phase 4: Integrate

In phase four, we want to pick something from the story to make part of ourselves. You can create a memory card to preserve something important about the story:

what moral you take from the story

a quote from it (e.g. “the die is cast”)

a pun or joke (e.g. “what’s stupid about the ‘Jeep Rubicon’?” “you could drive over the real Rubicon in a Chevy Metro!”)

an ironic summary of the story (e.g. “The Roman Republic thought it could protect itself from a brilliant general with a piece of paper and a foot-deep stream.”)

Practice B: Post a picture

Regardless of what you do, you then want to channel your feelings for the story and draw a simple small picture that you’d like to burn into your brain. Tape it up onto the wall right about the appropriate dot. As time goes on, you’ll fill up your home/school with these images, which will be a great way to remember everything you’ve learned.

The spiral continues

History, done right, doesn’t just teach what happened, but makes us feel that it matters. By the time they leave elementary school, kids can get a sense of how big the past is, and to see that the future is coming.

I.I.: You talk a big game, but these are just simple stories.

Oh, we’re not done. These stories are deliberately simple. They’re designed to stick, because we’re going to return to them, in proper spiral-fashion, in middle and high school. There, the stories will be expanded, complicated, and seen through whole new lenses.

To see all that, stay tuned for our next wireframe. In the meantime, please fill the comments with anything you don’t understand, think we’re missing, or know we can improve on.

© 2026 losttools.org. CC BY 4.0.

Historical fun fact: educational traditionalists sometimes accuse John Dewey personally for cutting history from the curriculum. But as arch-traditionalist Diane Ravitch points out, that’s not true: early progressivism actually had some pretty awesome history lessons. The dwindling of the subject happened gradually.

I remember staying up late with my sister, helping her memorize all the U.S. presidents in order — an ability she retained for one full week afterwards.

This is why, when you’re watching a re-run of the classic 90s TV show Family Matters, you can experience a wicked vivid flashback to the precise level of the first-person-shooter Doom that you were playing when you last watched that episode. Or, um, so I’m told.

Cue every single one of my history professors wincing simultaneously.

I have a history degree, and I still find it incredibly frustrating to remember that a date like 399 BCE (the death of Socrates) is in the “early fourth century”.

Note that the dates given in Ray Troll’s image are different from the ones I list for these rooms; I think mine are the most up-to-date numbers, but if anyone would like to check this, I’d be grateful. Note: we’re lumping the epochs of the Paleocene, the Eocene, and the Oligocene into the bigger period of the Paleogene, and are similarly lumping the Miocene and Pliocene into the Neogene.

I'm so glad you are planning to help curate the list of 100. The idea of the memory palace is new to me and I'm eager to implement it. I'm so very glad to see that the movement will be from room to room rather than camping in one room for a month or two. History has always been my weakest subject. (And hiding the labels, dots and images on the walls of our home from the young earth family and friends might be our biggest hurtle!! That it's something I'm still grappling with just adds complication.) In fact, just yesterday my son was asked what he's learning in history and he gave the dear in headlights look... "I don't think I'm learning anything about history..." quizzically looks at me... (Yes, it is in our curriculum. Yet somehow he doesn't think he's learning anything? Aside from the fact that we are working through the Science is Weird curriculum which is packed with historical facts.)

Anyway, choosing the 100 stories and how to tell them feels mega hard. I've been teaching history by country; spending each week in one or two countries- which has felt like drinking from a fire hose. But I think it has still been beneficial? I hope. We spent one year in Africa, one year in Asia and are currently in the middle of Antarctica, Australia & Oceania, Caribbean, North, South & Central America. Next year would then be Europe. How will you cover all of these countries fairly with only 100 events? Eurocentric history has been nearly impossibly hard to get away from. "History is told by the victor" being something that has me doubting that our records accurately depict the past.

I will have to decide whether to continue on our course and finish up with Europe or begin the palace approach. My son (Zeke...taking Comics now) is currently in 8th grade. Have you posted about how to adapt all of these wonderful frames to older students? We are working through the science lessons at an accelerated pace to fit them all in and so that hopefully he can join the live classes in the 27/28 school year. It is a bit overwhelming to think of doing a complete overhaul but these frames you've been sharing resonate with what I've been looking for since we started homeschooling 8 years ago! So, thank you!!

Really enjoyed this as history is the subject for which I currently feel least confident about our approach. What we've done so far with geography has helped a ton with their ability to connect new knowledge to existing knowledge, and I think this will help continue that. I had sort of been planning to use our neighborhood park as a memory palace since our house is not particularly well-suited. But physically placing markers sounds really helpful so I guess I'll try to figure out 22 distinct spaces in... a hallway and a greatroom.