Why you should teach your six-year-old the IPA

How to learn a second language, part 3

So, to recap: we’ve talked about tuning your ear just to hear the sounds your adopted language makes and tuning your tongue to make them yourself. We’ve also talked about how to use this perfect pronunciation to lock in vocabulary quickly. Throughout, we’ve talked about how to use a ridiculously geeky tool — the International Phonetic Alphabet (called “the IPA” by its friends, and “ði ɪn.təɹˈnæ.ʃə.nəl fəˈnɛ.tɪk ˈæl.fə.bɛt” by its lovers) — to help your kids do this faster.

I understand how weird this sounds. Of the millions of elementary school language classes, precisely none use the IPA.1 When I talk to folk about this, I’ve gotten good at predicting the moment their face will scrunch up in confusion:

Here, I’m going to limn out why teaching your kid the IPA (the relevant parts of it, at least) is absolutely worth the bamboozlement you’re going to experience. And to do that, I’m going to go wide. If its only benefit was to learn a new language, I think it’d probably be worth it. But if we go through all that work, we’re going to squeeze it for as much as it’s worth.

There are at least two exciting ways we can use the IPA across the curriculum — to enrich history and to explore sociology. We might also be able to use it in two other ways — to help kids learn to read in the first place, and to help them correct any speech impediments they have.

At the end, I’ll share an insight this has given me into what the goal of Egan education is in the first place!

One note: I’m framing this as “teach your kids the IPA”, but really the IPA is just a tool to help us build a robust skill of hearing and making sounds. You could theoretically do all this without the IPA. You could also focus on the symbols of the IPA and not learn to hear and make these sounds! So know that when I say “learn the IPA”, I mean “use the IPA as a guide to exploring all the wild noises a human mouth is heir to.”

1: Use the IPA to enrich history

You might assume that, as the proud possessor of a degree in history and as a former world history teacher, I must have a passing familiarity with Chinese history. I assure you that I do not. I’ve read books, but none of the history sticks. If you name a dynasty, I can’t reliably place it within a thousand years.

Reading John Psmith’s sharp, beautiful review of the book Imperial China caused me to reflect on why I suck so profoundly at this. There are the usual reasons that people point to, of course: it’s big (3,000 years of writing will do that to you), I don’t know the geography well, and my usual historical categories (e.g. ancient/medieval/modern) don’t apply. But more important than all that, I realized, is the fact that none of the names stay in my head, because I don’t know how to make the sounds.

Take Zhu Yuanzhang, the rags-to-riches founder of the Ming Dynasty who was one part Napoleon and one part Stalin:

How the heck do I say his name? I’ve tried a half-dozen times now, and it comes out a little different each time. This makes it impossible to remember his name. When we make a memory of a word, we’re getting webs of neurons to fire together simultaneously, and one of the most important webs is “how it sounds”. Well, I don’t know how it sounds; I’m stuck with trying to memorize the spelling of a transliteration that I suspect is only one-third accurate to begin with.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Boo hoo? Is this really a problem?

This is a big problem for Egan education, which uses history to glue together much of what we learn. (See especially our previous patterns of BIG HISTORY°, EPIC STORIES°, and SPIRAL HISTORY°.) So here’s the idea: when you learn foreign names, use the IPA to say them right. It is, after all, the international alphabet.

I.I.: It takes work to learn to make a novel foreign phoneme.

It does — but you can work toward it gradually. In the meantime, writing the name in the IPA lets you leap forward in your pronunciation. To use Zhu Yuanzhang as an example, I can type this into ChatGPT:

Act as a linguist. Give me a breakdown in IPA of how to pronounce Zhu Yuanzhang, the Ming Emperor, the way that modern Mandarin pronounces his name. Teach me how to make any unfamiliar sounds.I.I.: You’re gonna trust ChatGPT for that?

You’re going to trust the standard transliteration? I assure you, you are not placing your faith in something trustworthy. Anyhoo, I get this:

IPA:

• Zhū: [ʈʂú˥]

• Yuán: [ɥɛ̌n]

• Zhāng: [ʈʂáŋ˥]

Tips:

Curl your tongue back for “zh” and release it like “ch” but with a retroflex position. Round your lips firmly to produce the front rounded vowel [y] (as in the “ü” sound).In some ways, this seems pretty hard! I don’t know precisely what sounds the symbols ʈ, ʂ, or ɥ make. But I have the hunch that ʈʂ is closer to my “ts” than to the “Zh” in Zhu Yuanzhang. To check, I Google “Zhu Yuanzhang pronunciation”, and listen to someone saying it a few times.

I was right! Even before I learn those symbols precisely, I’m getting a lot closer to the Mandarin pronunciation. So I write down my version of how to pronounce his name — tsu-yang-TONG — and practice saying it a few times. Eventually someone should make a proper curriculum around all this, but for the moment, this’ll get me further than I had been before, even if I totally ignore the tones.2

I.I.: How do you imagine this being used?

Not just for Chinese. We can use this to learn the true names of some of the most important people across history — Genghis Khan, Nikola Tesla, Vincent van Gogh, Mao Zedong, and Julius Caesar, for starters.3 Working to learn these pronunciations helps lock their names (and their stories) into memory. It also conveys some of their foreign flavor.

I.I.: That word “foreign” worries me. I don’t want to see other languages as “other” — I want to understand them empathetically.

Me, too — but we have to be mindful how we can get there.

People sometimes object to getting excited by how cultures differ. This comes from good intentions: we know how easy it is to think of our own group as “normal” and others as “bad”. It seems wise, then, to de-emphasize anything that could make other peoples seem “foreign”.

The tragedy, though, is that this can quickly lead us to ignore real differences, and remake other people in our own image. We can end up erasing their values and experiences, and paving over all the richness of humanity with our assumptions about what’s “normal”, which was precisely the thing we were trying to avoid in the first place. To add injury to insult, we drain much of the interest out of history.

So we want to push back against our (understandable) tendency to strip out the “foreign” feel to other names, even while emphasizing respect. Making an effort to get people’s names right, especially when it takes some work, locks in an empathy for other cultures. As the phoneticist (and friend of the newsletter) Tom Harris told me —

If everyone could be more familiar with making these weird and wonderful sounds from an early age, it would go a long way to promote multicultural sensitivity.

It also paves the way for other languages to be learned more easily later in life. (It’s easier to start learning Mandarin if you’ve already learned how to make many of its sounds.)

2: Use the IPA to do accents & voices

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a brainy human child entering adolescence, must suddenly start imitating other people’s accents.

It’s not just teens; geeky adults are complicit, too. And it’s not just accents: we seem to be pulled even harder to the voices of movie characters. (You can’t mention “Gollum” around some people without them breaking out into their best rendition of “Myyy PRECIOUSSS!”)

Is this irritating and massively embarrassing? Absolutely! But we can use this desire to do something impressive: help middle schoolers understand the subtle nuances of speaking their own language.

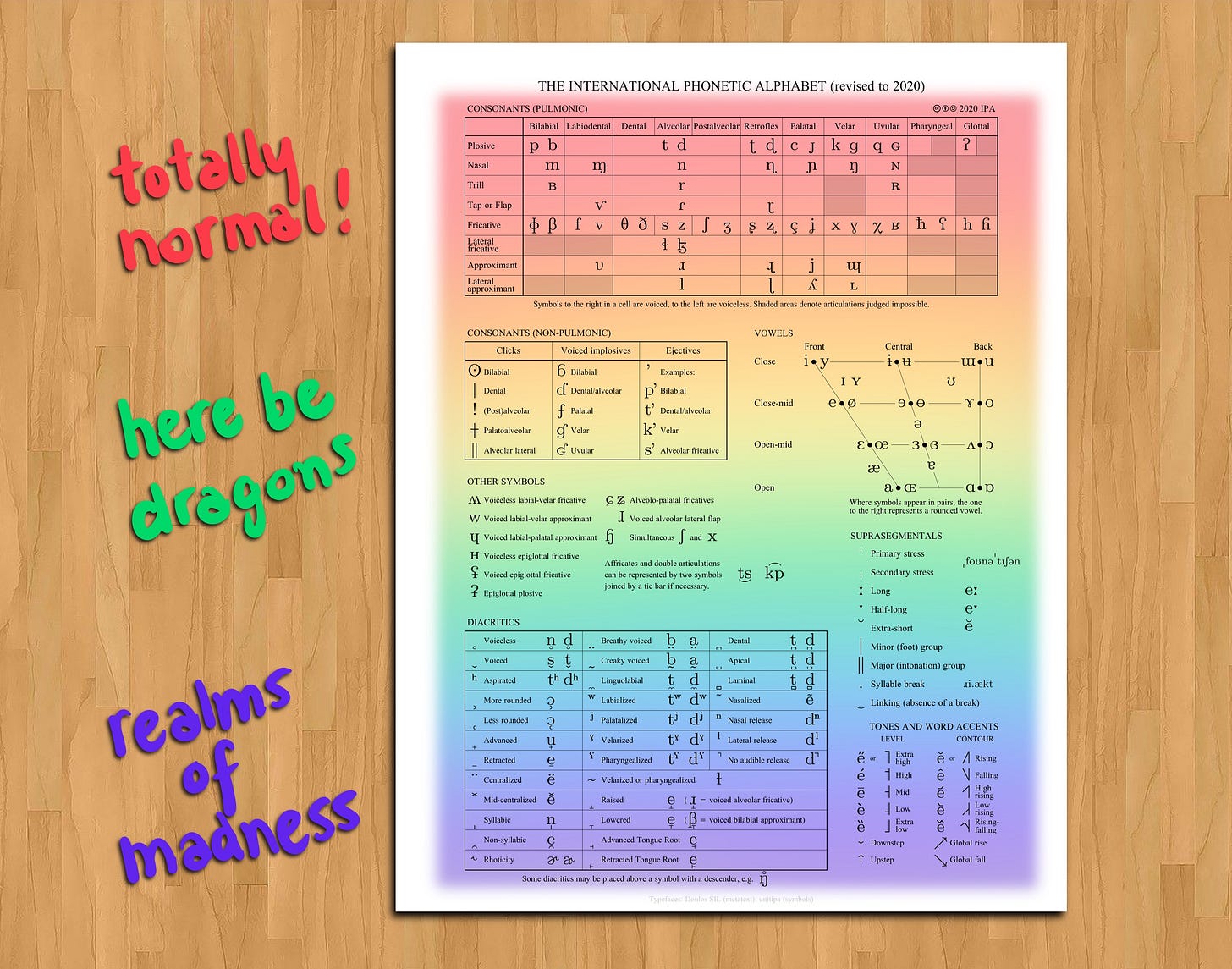

And probably this should wait for middle school — not just because that’s when kids get their most insufferable, but also because they’ll need to have mastered the basic IPA consonants and vowels. That’s right: we’re entering the terrifying world of diacritics! There’s an easy part of the IPA chart, and there’s a horrible part:

Diacritics are found down at the bottom, next to the tones.

I.I.: Wait, we can do accents now? Isn’t that taboo?

Some are, in some situations — and helping kids wrap their heads around this is an important piece of education, too. These taboos are unwritten and complicated. There’s an important philosophical conversation to be had over whether it’s ever “wrong” to to put on a particular accent, and you’ll want to have this with your kids. But regardless of where you come down on the theoretical ethics, you should know that some instances of this will land them in hot water.

I.I.: Which accents might we start with?

You can start with national dialects. Assuming you’re speaking American English, you might want to start with the tony British “Received Pronunciation” upper-class accent of Downton Abbey. You could move on to an Irish accent, a Scottish accent, and a Canadian accent. Each of these will get you to pay very close attention to how you’re shaping your vowels.

After that, you can try your hand at some of the regional accents inside your own country, starting with those spoken by people you know. For my family, that might include Boston, the “high Southern” accent of Charleston, a Texan drawl, and the “Yooper” of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

I.I.: What’s the point of learning regional accents?

When we speak, we’re not just communicating an overt message, we’re also sharing a picture of our past — where we grew up, who we spent time with. When we become aware of this, we can begin to understand others better.

Obviously, when accents are obvious, kids will do some of this instinctively. (Occasionally this creates awkwardness: “Dad, why is he talking like that?”) But more often accents are subtle: a few shifted vowels here, or dropped g’s there. Learning this explicitly helps us become more awake to the wild linguistic diversity all around us.

I.I.: Isn’t it just safer to not ever speak in anyone else’s accent, ever? Can’t we just learn about the accents, rather than saying them?

If you do that, you’re abandoning what might be the most deeply educational aspect of this: most of what we feel as “exotic” is, in fact, entirely normal. We need to help kids understand the quip of the Roman slave turned playwright: “I am human, nothing human is alien to me”. We want them to experience this “foreignness” so they move through it toward an empathetic understanding of another culture. Egan points out that as we go, we realize more and more than our native ways of doing things are no more “natural” or “normal” than any other. If they’re weird, we’re just as weird! If we’re ordinary, they are too.

But, y’know, if you’re too scared to do this, you can just stick to using the IPA to help kids do the voices of TV and movie characters. As Tom Harris tells me:

Character voices are just accents, which are just choices about which sounds to use where.

Honestly, even if you’re not too nervous to try to talk like a character from Downton Abbey, you might want to start by honing your Gollum, or Yoda, or Bugs Bunny.

3: Use the IPA to… learn to read?

My hunch — and it’s just a hunch — is that learning the IPA might help kids learn to read in the first place.

[Edit: Becky S. Hayden raises some excellent points in the comments, and I'm now more wary of this.]

What’s powerful about the IPA is that it’s the Alphabet to Rule Them All, the One True Alphabet. Heck, a better abbreviation of the International Phonetic Alphabet might be just “the A”, because it does what the original alphabet did for the Greeks: give a 1-to-1 correspondence between speaking and writing, between sounds and squiggles.

I.I.: But the IPA is far too complex, right? It has, what… 111 symbols?

Sure, because there are ~111 sounds in all the world’s languages. English only uses around 40 sounds, however, so to help kids read, you only need to teach ~40 symbols.

I.I.: 44 is a lot more than the 26 letters of the English alphabet, though.

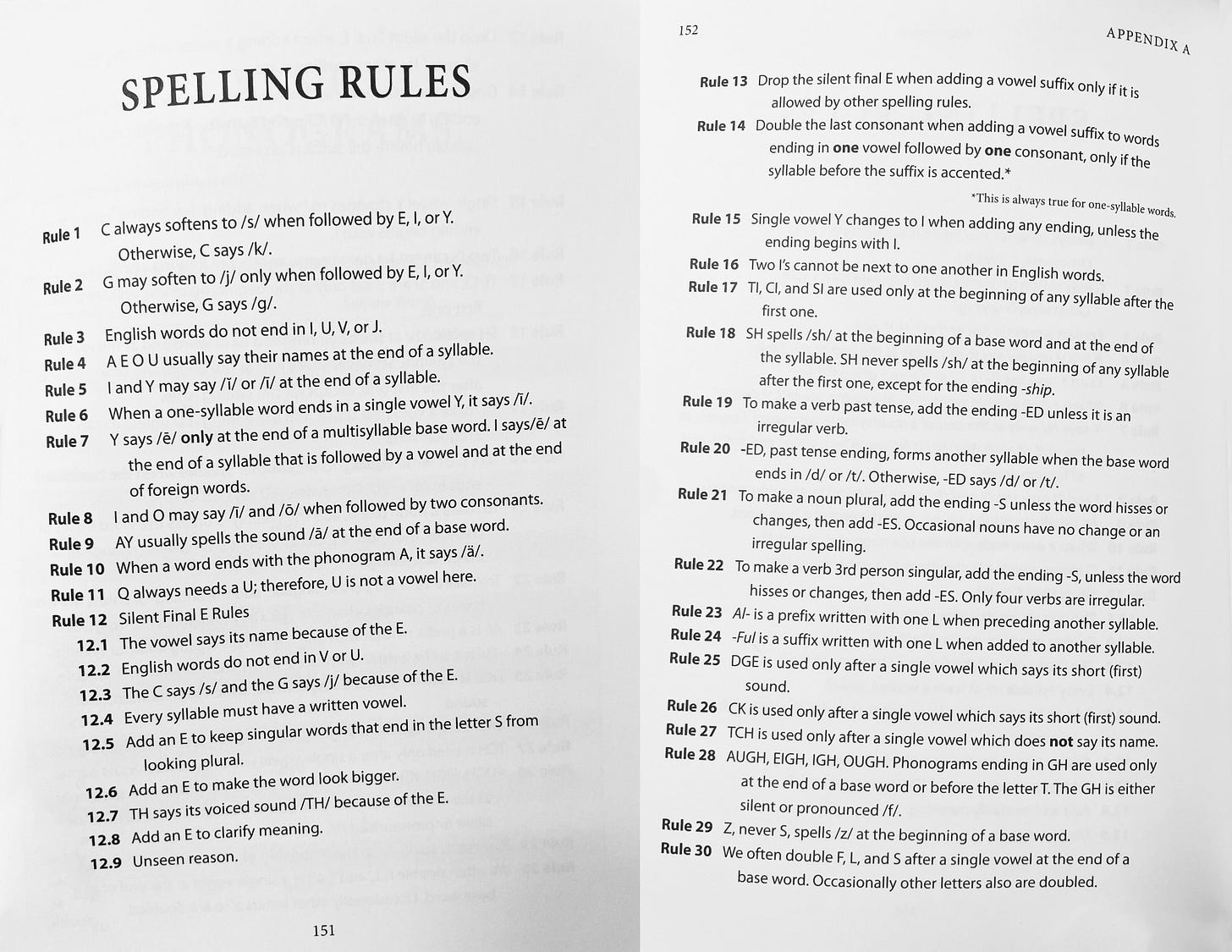

Fewer isn’t better. We have 26 letters, but need more than 30 separate rules to make them fit our spelling system most of which we never actually teach kids. Here’s a full list from Uncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and Literacy:

Note that Rule 12 (concerning the “silent e”) is actually nine rules, and that the final one is “my God we have no idea” which includes the e at the end of “done” and “where” and “giraffe”. So really, we have 26 letters and and 39 rules. Doing the math:

26 letters + 39 rules = 65 things to remember

65 > 40And the sounds and symbols aren’t complicated — they’re just a matching game. (When you learn the rules, by contrast, you need to remember which words to use them on, which still occasionally have a few exceptions.)

By this reckoning, learning read with the IPA could be easier that learning to read in modern written English.

I.I.: Kids need to learn spelling, though! They can’t write emails in the IPA!

Absolutely correct: spelling should be taught with power. (Somebody really needs to get on the project of Eganizing a proper spelling curriculum — like the above-mentioned Logic of English. If you’re interested in taking this on, get in touch!) But I wonder if it’s a mistake to try to teach English’s weird spelling rules at the same time we teach reading & writing.

If I’m write right, then teaching the IPA first would give kids a beachhead in reading & writing before they have to take on the eldritch horror that is the English spelling system. (And it really is. Did you know that kids who grow up speaking French or English take years longer to learn to read than kids speaking Italian or Spanish? Part of America’s illiteracy crisis is due to our language itself.)

If I’m right. Again, I’m not sure about this, and would love feedback from people who’ve had experience teaching little kids to read. (If you’re a new subscriber, you should know that I’ve written more about how to help kids experience English spelling in the patterns ORIGINS OF THE ALPHABET° and OTHER ALPHABETS°.)

4: Use the IPA to correct speech impediments

I was talking with my 15-year-old about all this, and he was interested — but said, “but this wouldn’t work for me, because I still don’t know how to use all the sounds of English”.

He has a speech impediment that has survived numerous attempts by experts to fix. This galls me: I had a speech impediment when I was a kid, and if I’m being honest still don’t speak with as much precision as I’d like.

My hazy, hazy hunch — held with even less conviction than #3 above — is that bringing the IPA into the whole curriculum from an early age would help a lot of kids correct their speech impediments.

Some of this is because the IPA allows us to differentiate between sounds that have the same spelling, but a bigger reason is that it would help kids always be thinking about the subtle sounds their mouths are forming. Speech impediments are habits — and this is a way to stay fresh, to keep nudging ourselves out of ruts.4

5: Use the IPA to make language freaks

Long-time readers will know that I’ve spent the last decade struggling to elucidate what I find so wonderful and powerful in Kieran Egan’s paradigm. Well: I think, in writing this post, Alessandro and I have come up with a new way to express this. Here’s a hint of it:

Q: What’s the goal of the language curriculum?

A: To make kids into language freaks.

By “freaks” we mean “nerds”, “geeks”, “zealous fanatics”. The sort of people who wake up thinking about the topic, who talk about it constantly, who make breakthroughs on its problems in the shower. The sort of people, that is, that schools very rarely produce — even ones that train kids to speak Spanish and write English well.

To do that, we need to to suck kids into the joy and weirdness of human language. Alessandro quipped, “we need to make schools into freaking sound dojos.” And the IPA seems to be a “supertool” — an intriguing term Egan coined, but never quite defined — to help us do that. It’s easy to imagine it being misused, to be treated as the goal itself, rather than the means to falling more deeply in love with language. But it’s one of the big guns of modern linguistics. We think it can help inject more humanity into the whole curriculum.

I.I.: Speaking of which, what’s your new insight into the goal of an Egan education?

Let’s give it a pull quote:

Q: What’s the goal of the whole curriculum?

A: To make kids into freaks of every discipline.

We want to help kids become history freaks, math freaks, literature and science and physical education freaks, and more besides. Our goal is to help them feel the pull of these slices of the human experience, and to crave achieving excellence in the academic subjects that have been set up to study them.

On one hand, this sounds incredibly romantic: is this even possible? On the other, something like this was the explicit purpose which the academic curriculum was created to fulfill, from Plato to the present.

I.I.: I don’t have a degree in marketing, but “make freaks” probably isn’t the best way to sell your philosophy.

Probably not! But, at the moment, it seems like the clearest way to express what we’re trying to do.

Next up: Grammar!

Would you guess that this was supposed to be a quick little post? Writing is like that, sometimes. In the next post, I plan to wrap up this series as to what an Egan foreign language curriculum could look like by talking about how we (1) teach grammar in a Fluent-Forever-amenable way by (2) pulling together some of the other patterns we’ve been talking about on this blog.

If you know of anyone who does, put it in the comments, and I’ll edit this to shine a spotlight on them.

They frighten me.

Genghis Khan: /’tʃiŋgɪs xan/, not GEN-giss kahn

Nikola Tesla’s first name: /nǐ.ko.la/, not NICK-uh-luh

van Gogh: /vɑn ’ɣɔx/, not van-GO

Mao Zedong: /tsɤ̌ tʊŋ/, not zeh-DONG

Julius Caesar: /ˈju.li.us ˈkai.sar/ with a “y” and a “k” sound, rather than a “j” and a “s” sound.

I believe that some of you, dear readers, are speech pathologists. If you’d be willing to chime in on this (either for or against), I’d appreciate it.

Logic of English gives a great foundation to the IPA, it might just be a matter of adding the symbols in where desired.

"Phonemic Awareness" is a regular section of the lesson plans - how a sound is made, hearing the difference between sounds, and the manual includes notes on various accents.

The Spelling Journal is sorted by sound, giving all the different spelling options in one place, and includes notes on related spelling rules under the phonograms. (I've added additional notes in mine.)

Egan-friendly aspects of LOE:

-When reciting spelling rules, she encourages students to use funny voices, giving variety and humor.

-Her Rhythm of Handwriting method, incorporated into the manuals, includes verbal cues and she gives ideas for a variety of somatic experiences.

-Some of the reading practices involve riddles and clues to puzzles.

-She includes backstories on how pronunciations and spellings have changed over time, both for individual words and general trends.

That's just off the top of my head... I've used a range of her materials and would be happy to discuss them more in-depth if needed!

I've started reading Fluent Forever and it's fantastically written and I love the fact that it has grounding in cognitive science and practical, hands-on application. As I've been reading I've been thinking about testing out the theories by trying to jump back on the horse and learn Cantonese again.

But I'm actually at the stage before that: learning the IPA. I'm not exactly sure how to progress because I don't know how much of the IPA to learn. You see, as an English teacher to students who are native speakers of Chinese, it makes sense to at least know enough of the IPA to be able to represent the 44 sounds of English, plus a few more for dipthongs and common North American pronunciation. I've got a decent chunk of that down. If I wanted to know the IPA for Cantonese there's a whole other set of things to learn, not least the symbols for tones. To learn everything seems like it wouldn't be worth it because I don't have enough real-language referents to match them to. It could make most sense to learn the IPA for your target language, and add new sounds as you are introduced to foreign words or new languages.

That brings me to the question of what to do with the existing transcription systems for Cantonese and Mandarin. I've learned pinyin well enough that I can read Mandarin Chinese terms with decent pronunciation and the Cantonese equivalents Jyutping and the Yale system are certainly helpful and I can parse them better than IPA. The issue isn't only learning IPA for Cantonese, it's that language learning materials generally don't use IPA. At least for English-speaking learners they tend to use these established transcription systems and so IPA only helps as a third contact point. It's nice but not essential.

When I bring up IPA to other language teachers, the most common response that I get is that it's simply ANOTHER coding system you need to learn and that it's confusing to teach two at the same time.

So where does that leave me? I'll definitely learn the English-relevant IPA sounds (I already know the vowels) and then see how much additional outlay Cantonese requires. I'm going to be making some major changes to our phonics curriculum next year and I might try introducing it as a cipher and then setting it alongside newly-introduced sounds. One immediate use for me would be illustrating that different letters can make the same sound and the same letter can make different sounds.