Spaced Repetition Everywhere

The 54th in the Egan Pattern Language

Note: It’s been a summer! you’ll find an announcement (or two) at the end of this post.

What if an education wove in the master tools that (cognitive scientists gush) drive the most serious learning — spaced repetition, deliberate practice, and habit formation?

I think of these as “the big guns”. And Alessandro and I were exhilarated to realize, as we drew up the blueprint for K–12 Egan education over the summer, that we’re already weaving them into every age and subject, from kindergarten to high school, from arithmetic to zoology.

Today, I want to share just a taste of how we’re weaving in spaced repetition.

Hey kid: want to remember everything?

I’ve already written about spaced repetition in our Forgetting Curve Box° pattern. The most fun place to start, however, might be Gary Wolf’s classic article for WIRED, “Want to Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm”.

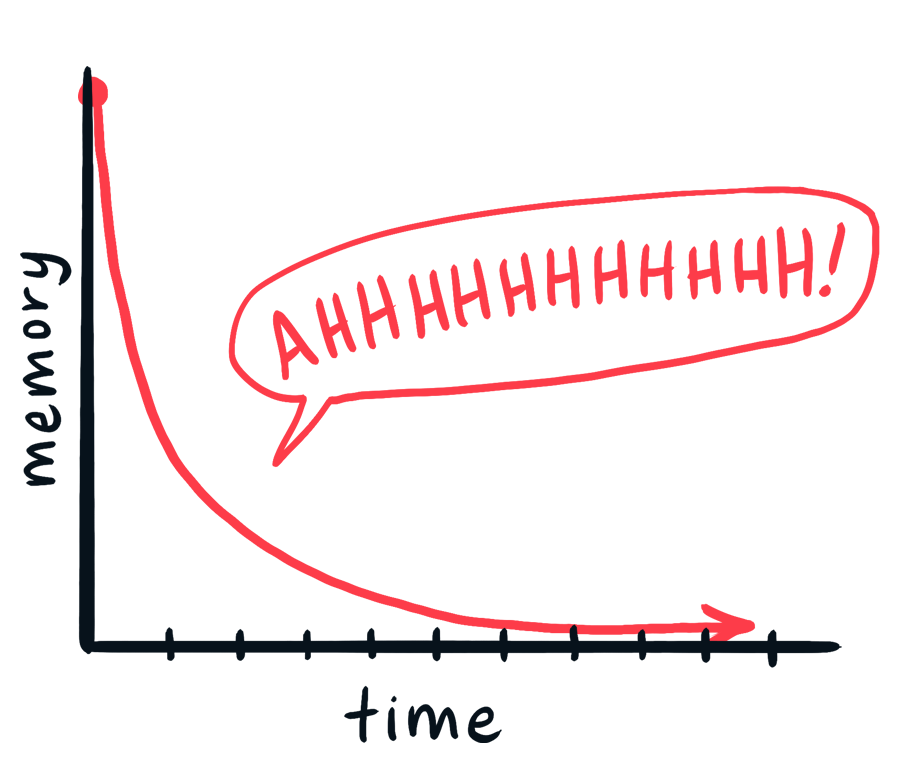

The tl;dr is that we forget almost everything we learn. This is bad! It’s the undoing of all the work we put into education. Forgetting is, the cognitive psychologists say, the biggest problem in education:

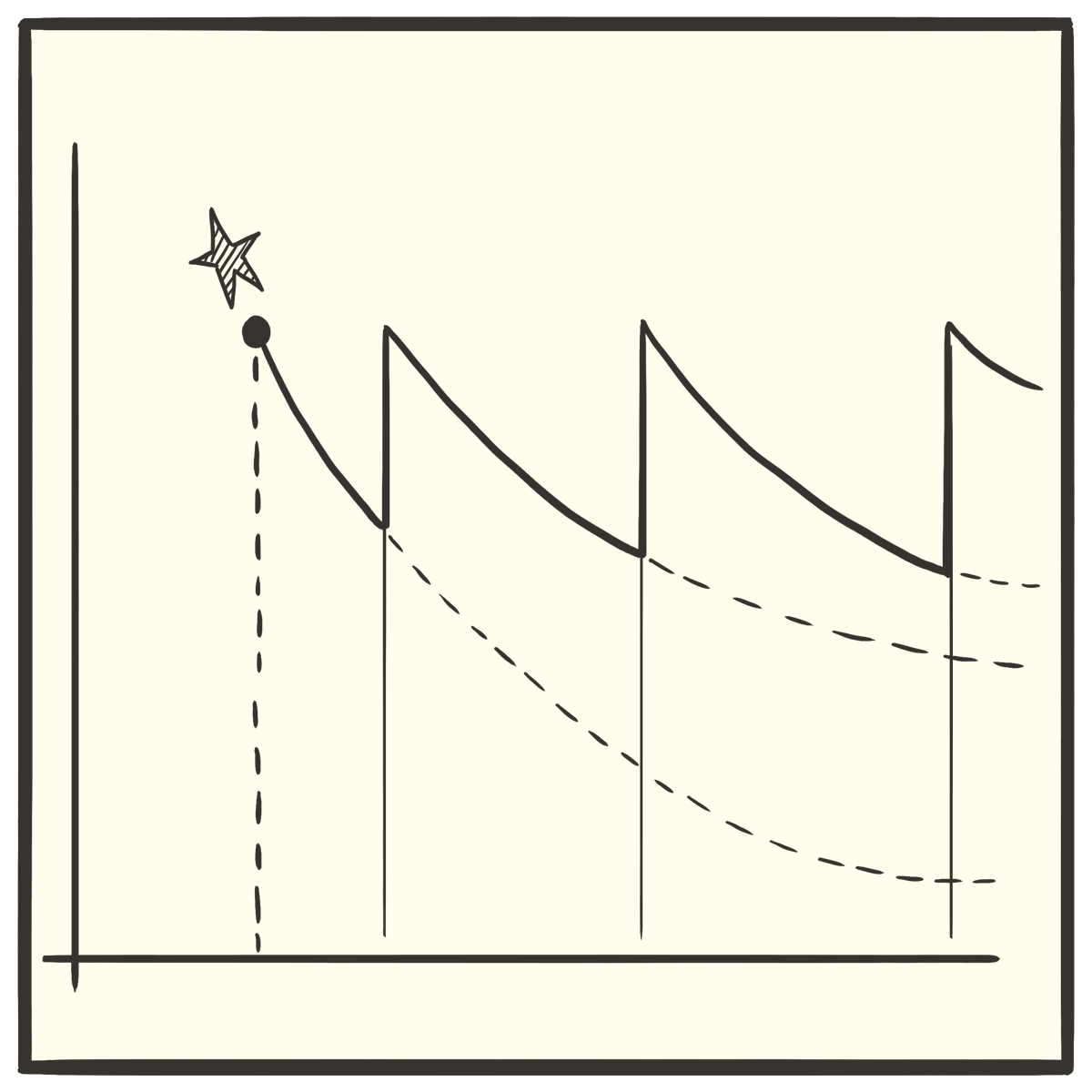

Psychologists have dubbed this “the forgetting curve”, and have known about it since the founding of psychology.

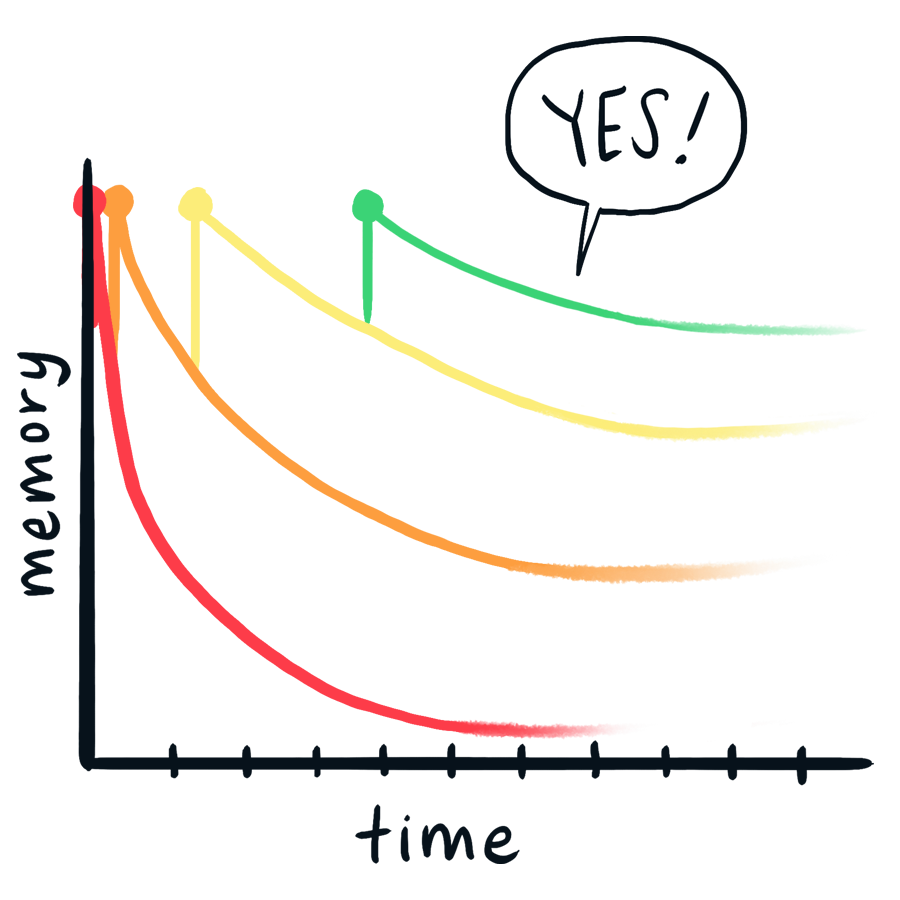

Thankfully, they’ve also figured out how to fix it: re-quiz what you learn at ever-increasing intervals. That is, after you learn something, review it after…

a few minutes, then

a day, then

a couple days, then

a week, then

a couple weeks, then

a month, then

a couple months, then

a year, then

a couple years, then

a decade, and then

a couple decades.1

Does that sound like a lot? It’s not: each of these reviews takes just a few moments. That means that with a sum of just a few minutes of properly-timed review, you can remember anything you want for the entire rest of your life.

Psychologists call this the “spacing effect”, and they’ve spent the last 150 years asking educationalists to please please incorporate this into education.

Educationalists, meanwhile, have mostly remained cold to this. Why?

Asking this question (at increasing volumes) has become popular amongst psychologists. My favorite is a 1988 article by the cognitive psychologist Frank Dempster, whose scorn comes through in his cheerfully passive-aggressive subtitle: “The Spacing Effect: A Case Study in the Failure to Apply the Results of Psychological Research”.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Do schools ignore this because it doesn’t actually work?

Oh, no — it works like magic! Spaced repetition might be the best-attested discovery in all the learning sciences. And if you don’t trust academics, just look to the growing community of people who use apps like Anki to hack their studying. (I can attest to this personally: over 15 years I’ve created more than 10,000 cards, the vast majority of which are now second nature to me.)

I.I.: Is it because long-term memory is overrated?

Alas, no: the educational establishment continues its long and proud tradition of underrating long-term memory. In schools of education, “memorizing” continues to be an insult, even though (as the genial-but-combative cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham points out) making memories is what education is. And “rote learning” is a term of abuse even though that is what spaced repetition is.

I.I.: Okay, I fold. Why hasn’t this taken off in classrooms?

The best answer that I know of comes from the always-thoughtful writer TanagraBeast, who reflected on his experiments of doing spaced repetition in an English classroom in the classic essay “Seven Years of Spaced Repetition Software in the Classroom”. And what he found is that the champions of spaced repetition have made a crucial mistake. To quote the summary of the essay by Andy Matuschak:

in a classroom context, apathy is the main problem, not forgetting. SRS makes this worse because it’s boring.

In other words: when students don’t care about what they’re learning, they’ll hate repeating it.

What Alessandro and I wondered is… could we fix this? (Spoiler: yes! Because, Egan.)

Back when we were just worms

As I suggested in this newsletter’s first real post,

the matter with schooling is that schooling doesn’t matter.

I.I. Well, duh. But how can we make schooling matter?

I don’t have a pithy answer to this — this is what I’ve been working to answer in my ACX book review, as well as every post on this blog, as well as the workshops I gave this summer. But the start to answering this has to go back to the very beginnings of our evolution in the Ediacaran, more than a half-billion years ago, when our ancestors were millimeter-long worms:

Fellow evolution-freaks may recognize this as a nematode, our present-day stand-in for the early ancestor we share with all mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, slugs, and starfish.2 And an interesting thing about nematodes is they’re able to feel emotions.3 That is, the original evolutionary purpose of a nervous system wasn’t to think conscious thoughts — it was to feel.

“Liking” and “disliking” is the fundamental way we wend our way through the universe. This is a huge fact about life, and one that’s been discovered multiple times; you don’t have to take the word of biologists for it. Psychologists call it “affective primacy”. Buddhists warn against it, and tell us that enlightenment can only be found when we snuff out craving (“taṇhā”). Secular philosophers like Hume say that emotions are what drive us, and that reason can only be their slave. Theologians deem us “desiring agents”: as one Reformed literary critic memorably puts it,

Humans… are ‘desiring agents’, full of longings and passions; in brief, we are what we love.

– James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom

So: if we want to weave spaced repetition into the fabric of education, we need to find ways to root it in desire.

There are three approaches Alessandro and I have come up to do this:

make a memory box,

stretch a single topic over multiple years, and

forge friendships with specific works.

Each approach has its strengths, and works best for a certain subjects. If we put them together, we can finally cash in on the discovery of spaced repetition, and open up the (rather amazing) possibilities implicit in human memory… which go far beyond what we usually think of as “memory”.

Approach #1: Make a memory box

We want to begin the earliest years of education not by making kids remember what we think is most important, but by helping them preserve what they love. And we can do this by making a memory box.

In short, at the end of each day reflect on what’s been learned, and hand-write a card to preserve one thing that the kid finds wonderful. Then, at the start of each day, review the cards that you’re about to forget.

I had written before out how to do this (and easily), but while doing the homeschooling workshops this summer, I realized that this belonged at the beating heart of an Egan education, starting even before kids can write.

I.I.: What subjects would you do this for?

Begin this in kindergarten or first grade by not tying it to any subject. Later, when you want to use this to master academics, use it for subjects in which knowledge naturally comes as facts: relatively simple bits of information that aren’t too connected to each other.

Geography

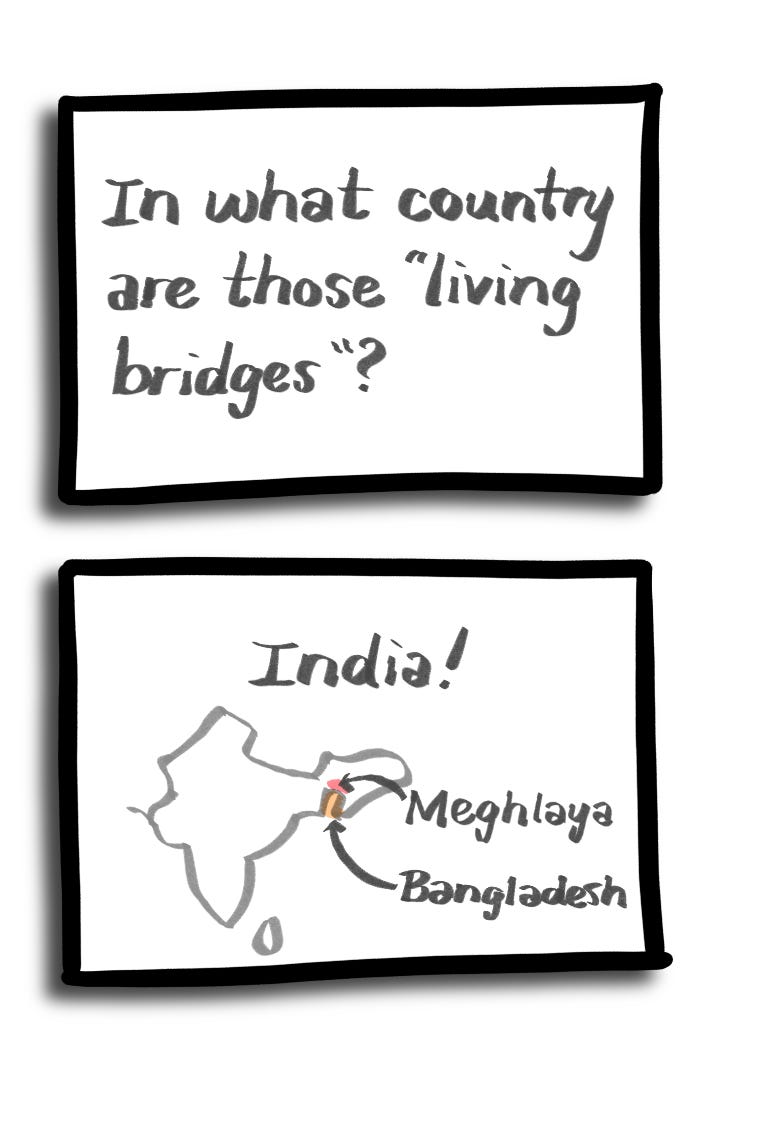

In geography, we start with marvels — wonders of the world that exist in each country.

These anchor places into memory. They make it easier to not just remember another country, but to find it interesting — and want to learn about it more. They are, for lack of a better word, naturally memorable. A card for each marvel might suffice:

Science

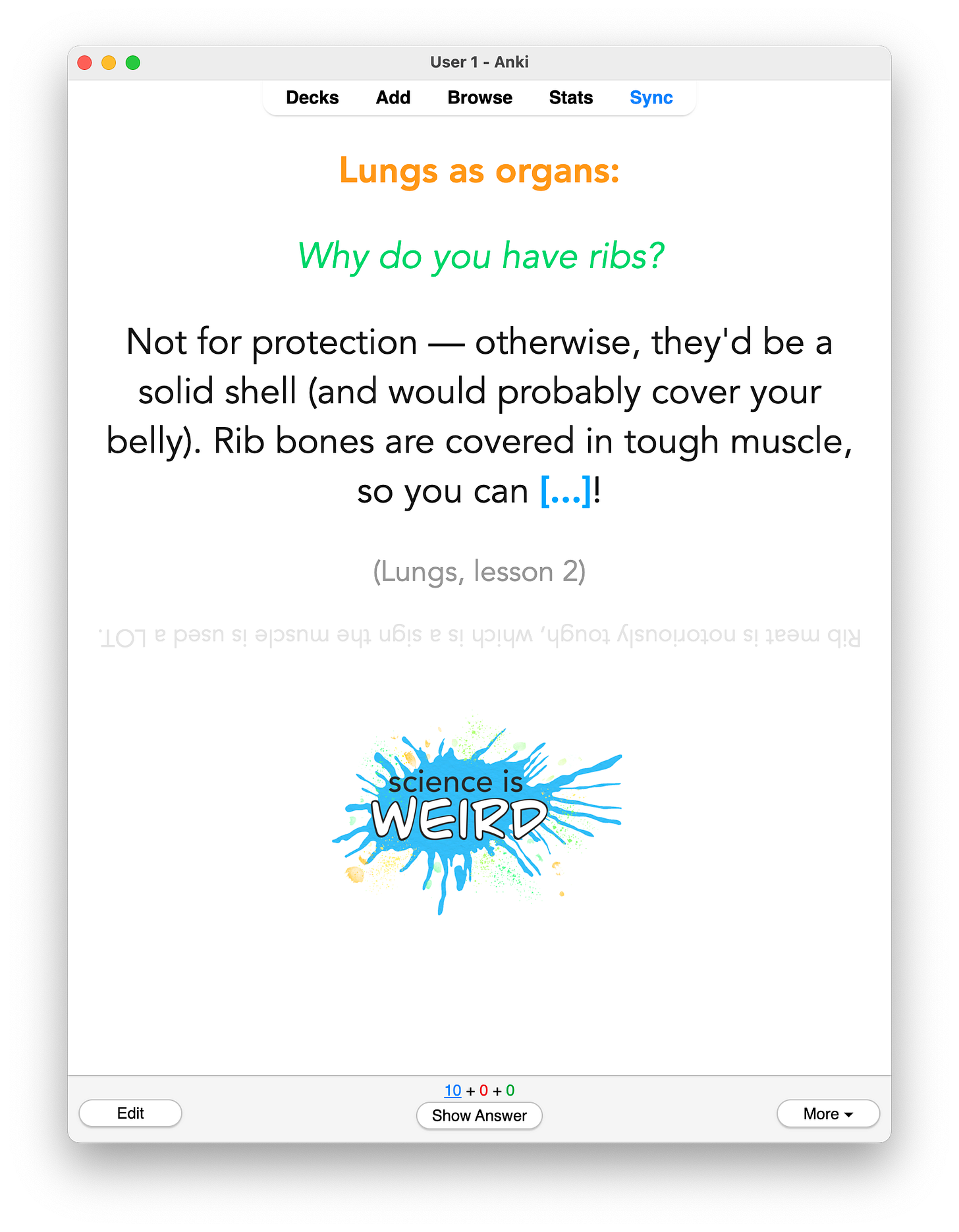

Conceptual scientific understanding, too, can be anchored with shiny facts about the world. Not for nothing does my team make about a dozen Anki cards for each Science is WEIRD lesson:

Reading & writing

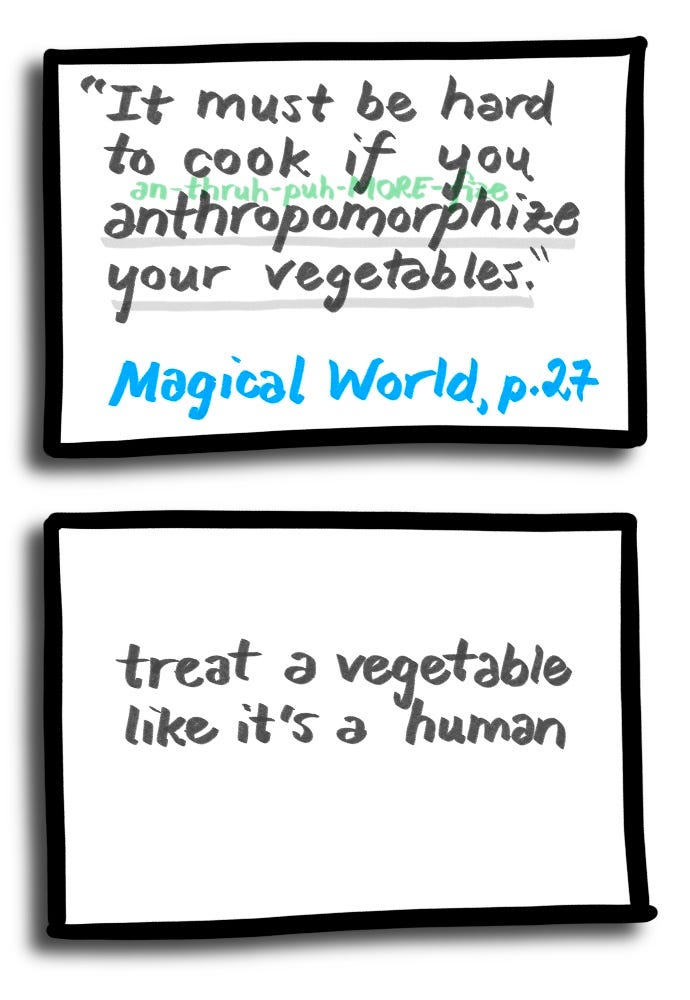

For vocabulary, it’s as easy as writing down the word & pronunciation on one side, and a simple definition on the other:

Well, it’s nearly as easy as this. Flashcard vocabulary can go terribly wrong if (like an educational traditionalist) you try to stuff reams of random words down a kid’s throat. The way to make it enjoyable is to include the context of something your kid wants to better understand in the first place.

What you need, then, is an engaging source of high-end vocabulary! Preferably one that’s funny, has pictures, and raises existential questions (but also the occasional pee joke). Yes, you know what I’m talking about.

Your adopted language

You can do something similar in the vocabulary of your new language, which I’ve already written some about. Here, the trick for making it valuable is to include a personal connection to each word — e.g. for the Spanish word gatto write the name of (say) the cat that bit you when you were eight.

But again, the memory box is best for subjects in which the ideal form of knowledge looks like a heap of facts. For subjects in which knowledge is an interconnected mass, try…

Approach #2: Stretch out a topic

The world is more than shiny facts. And in topics where the connections are more important than the details, a memory box won’t suffice. Instead, for those topics, you want to pick one topic — one thing — and go incredibly deep in your study of it over the course of multiple years. As you study it, you’ll see how it connects to everything. The repetition will happen naturally.

Kieran Egan created Learning in Depth° and Know a Place° to make use of this fact. We’re expanding it with curriculum pieces like Know a Tree° and Know an Animal°.

It’s foolishness to assume that depth and connection will happen automatically; to make this scale, we have to find ways to help kids enter into a topic. It helps to start with a topic they enjoy! For example, in Know a Place°, you choose a beautiful spot near your home, and learn about different aspects of it slowly:

Year 1: the story of its geology

Year 2: the story of the life in it

Year 3: the story of its interactions with humans

I.I.: But you mentioned “Learning in Depth”. Doesn’t that famously start with a topic kids find boring?

Indeed, and there’s a reason for that. Starting with something seemingly dull lets people experience the transformation of boring → fascinating, and prompts them to gleam that everything in the world might be just as interesting.

There are more ways this approach could be applied. The approach that Alessandro and I are most excited about, however, is…

Approach #3: Spiral specific things

More than anything else, this was our breakthrough as we pulled together these workshops. Aspects of this were presaged in the Deep Practice Book, but the insight was inspired in part by an image from one of Erik Hoel’s recent posts about teaching reading:

Erik trumpets the power of spiraling:

…the modern science of learning tells us that “spiral learning” is indeed incredibly effective, because it automatically builds in spaced repetition—the review and reminder of what’s been learned, spaced out at ever-increasing intervals. Such “interleaving” that mixes old and new things is vastly more effective than the “block learning” of most traditional classrooms.

The power of spaced repetition has been known for 150 years. It replicates and has large effects. So why is spaced repetition (or even its more implementable form of spiral learning) not used all the time in classrooms? No one knows!

One reason might be that “memorizing” has become a dirty word in education (the “rote” part has become implicit). Yet all learning involves memory: it’s a spectrum, which is why spaced repetition improves generalization too (really, it improves learning anything at all). The second reason is that the “block model” of learning (learn one thing, learn the next) is much easier to implement in mass education; just as a factory, by being a system of mass production, is made as modular as possible, so too are our schools.

His innovation is simple: we can somethings go beyond spiraling mere facts — we can spiral the engagement with the things themselves.

He does this with “early reader” books to help teach kids to read when they’re quite young. (Read the post; this application is brilliant.) We realized that we can do this to other things — say, works of art, pieces of music, and stories from history and world religions. And we realized the benefits are bigger than memory — if we stretch out the spiral over multiple years, kids can engage these things differently each time:

in elementary school, engage it SOMATICALLY (🤸♀️) and MYTHICALLY (🧙♂️)

in middle school, SOMATICALLY, MYTHICALLY, and ROMANTICALLY (🦹♂️)

in high school all of those plus PHILOSOPHICALLY (👩🔬) and IRONICALLY (😏)

That’s to say, these experiences can grow along with the kids.

I.I.: Aaaand you lost me.

The devil’s in the details, and we’ve realized that we need to actually show these possibilities (rather than just talk about them) to move this whole project forward. So in the fall, we’re going to start going through these practices week by week in video.

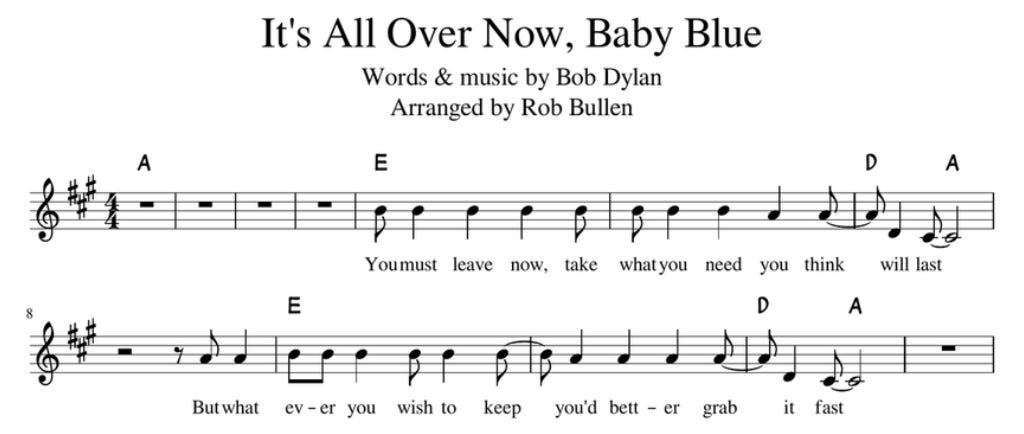

But for the moment, I’ll give a brief example in [rolls a die] music. Let’s take the song “It’s All Over, Baby Blue” by Bob Dylan, as he performed it at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Imagine we give this (along with ~99 other songs) to kids in elementary, middle, and high school:

In elementary school, you can engage it SOMATICALLY: get your body into it! Can you clap along to it, or sway? Can you hum the melody, or the background accompaniment? Can you illustrate it without symbols (as we laid out in Mysterious Music°)? Can you dance to it? You can also engage it MYTHICALLY: print out the lyrics (here’s the first stanza)…

You must leave now, take what you need you think will last

But whatever you wish to keep, you better grab it fast

Yonder stands your orphan with his gun

Crying like a fire in the sun

Look out, the saints are coming through

And it's all over now, Baby Blue

…and start asking questions:

why do I need to leave?

who’s the “you”, here?

why does my orphan have a gun?

why do I have an orphan?

wait, can one even have an orphan — isn’t that a contradiction?

why are “the saints coming through”

OH MY GOSH AM I DEAD?

I.I.: Wait, I recognize some of this…

Indeed, so far I’ve mostly been recounting bits and pieces from our pattern A SONG A WEEK°. The innovation is in what comes next:

Put the song away.

Let yourself forget this.

Come back in three or four years.

When you come back to the song in middle school, you’ll have grown up some, and your ways of understanding the world will have developed. You’ll have a clearer picture of the world, and will be interested in seeing where the song fits in (ROMANTIC understanding).

But your SOMATIC and MYTHIC understandings will also have grown up, too. So start with them! Repeat some of the exercises you did years ago, and go beyond them. (Sing along to the song! Can you play any parts of it on the harmonica, guitar, or piano? Can you commit a stanza to memory?)

Then use the fondness that comes with being reacquainted with the song, as if it were an old friend, to build ROMANTIC understanding. Who’s Bob Dylan? What was he doing at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival? Learn a little of the lore of that performance: why was Dylan booed during it? What did one woman in the audience mean when she screamed “Judas”? Why does everyone say that Pete Seeger — that famously calm and kind founder of the folk movement — tried to stop Dylan’s performance by smashing the soundboard with an ax?

This would be a good time to watch the biopic A Complete Unknown, which climaxes with this performance. (Also, any of a zillion Dylan documentaries.)

There’s more to do with this in middle school — listening to other (very different) covers of the same song, or trying to recreate some of Dylan’s genius performance on an instrument — but I’ll save those for the videos I’ll be shooting later.

And then, at the end of the week, put the song away again. Wait until high school to revisit it. Start (again) by doing some of the earlier activities, but this time have sheet music on hand. Use those to enter into some of abstract, theoretical, PHILOSOPHICAL discussion of the song:

What key is the song in, and what mode, and do those matter?

Dylan sings the notes a little behind the beats — does that matter?

Dylan’s voice is famously nasal and abrasive — what effect does that have on the song?

What makes these simple notes sound so good together?

These are questions that musicologists argue about. There are other questions that, say, a more literary-oriented critic might ask:

Is the tone cruel or compassionate?

What’s going on with the Biblical imagery? with the Surrealist imagery?

And there are other questions Dylanologists quarrel over:

At Newport in 1965, was Dylan killing folk music, or freeing it?

Who is Baby Blue? (Is it a lover? the hope of political change? Dylan himself?)

I.I.: Well, that’s one example. How about for history, or world religions, or the visual arts?

One thing at a time! As I said, all of this new stuff (and there’s so, so, so much more — it’s been a very productive summer) will take a new push to get out. Look for a new series to begin here in the late fall.

Wait, where are we?

I.I.: I see how this is fun, but — is it useful?

Let’s rehash where we’ve just been. We started by saying that psychologists have solved the problem of forgetting (spaced repetition), but that schools couldn’t use it, because it only works for things you care about.

Then we showed how we could put “caring” at the start, and begin by giving kids stuff they want to remember.

But where we’ve arrived, in the end, is to show how spaced repetition can increase how much kids care. Everything that gets revisited becomes an old friend. Your understanding evolves as you age: you don’t just care more, you care in new ways.

This is all to say: spaced repetition isn’t just an add-on for Egan education. Done properly, it’s the beating heart.

Announcement: Open houses this week

Like I said: it’s been a summer! The Egan homeschooling workshops went splendidly. I got pneumonia, or some other lousy virus that sent me into a months-long slog of a post-viral condition. I gave a keynote at a conference where I discovered I had fans.

And now, it’s all over — happy Labor Day, and happy 18th anniversary!4 I’m about to kick off the teaching year with two (free) open houses.

This Wednesday, I’ll be doing one for Science is WEIRD. SiW is the online teaching company I started five years ago to show off what an Egan-fueled science education could look like. It’s theoretically designed for kids 8 through 15 (note: 🦹♂️ROMANTIC), but we also get kids both younger and older. Many are gifted, ADHD, ASD, or some combination of those three.

We’re entering year three of our six-year curriculum. If your family joins, you’re likely to end the year having had dinner table conversations about the strangeness of electrons, why you (really) have a tongue, the secret backstory of your nearest big hill, and why evolution keeps making things beautiful. (Oh: you’ll also have made a lot of different kinds of ice cream.) You can sign up for that open house here.

This Thursday, I’ll be doing an open house for my two comics classes. In “Reading Comics”, I show folk how to read really closely — grokking every joke, noticing every odd turn of phrase — using strips like Calvin and Hobbes and The Far Side (and more). It’s a heck of a lot of fun. (Along with this, kids learn a heap of vocabulary, which we create Anki cards for.) In “Arguing Comics”, we choose issues raised in the week’s reading, and fight over them. I teach kids how to keep their minds open while they argue forcefully for their own opinions. You can sign up for the open house for both here.

Oh, and Learning in Depth starts a new 12-week cohort today! Congrats (and good luck) to everyone who’s in it; if you’re interested, take a look at our new website — learningindepth.quest. We’ve revamped the program quite a bit. If you missed it, the next cohort will start in January 2026; you can join the waitlist now to attend the open house that we’ll be doing on Wednesday, December 17.

Purists will note that this doesn’t follow the precise equation of the forgetting curve. Ultra-purists, however, will note that there are many mathematical attempts to capture forgetting, and that they all disagree a bit. The “just double, idiot” method above gets close enough for our purposes.

“Nematode” is a frustrating name — it makes it sound like it’s a “toad”, when in fact it’s just this teensy-tiny animal that looks like a thread. (And, indeed, nematode is Greek for “this thing that looks like a thread”. Helpful for those of us who still mend clothes in Greek.)

Or at least to “feel” “emotions”. Sticklers might want to put scare quotes around “emotions” because that term is sometimes restricted to the specific feelings of anger, disgust, fear, and the rest of the cast of Inside Out. They might also want to put scare quotes around “feel” because consciousness is hard, man, and experts disagree as to which kinds of animals can actually “feel” anything. Suffice to say, nematodes experience affective states… or, well, act like they do. As Max Bennett chronicles in A Brief History of Intelligence, they use dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters to steer toward food and away from danger. My thanks, as always, to Farid Aboharb for helping me to understand this story.

Mostly I’m aiming that at my wonderful wife, but if you’re one of the ~30,000 other people in the world who are celebrating that particular anniversary today, l’chaim!

I think I've said this before, but I'm so grateful to SiW for getting me over my Anki intimidation and into using it. One of my kids is really into birds, so when I suggested we work on the 40 most common birds via Anki she didn't have the patience to wait for me to figure out how to whittle down the Ultimate Birds deck and instead we've been working on all the birds in our state. This meant that the other day when she encountered a slide with five birds that all look kind of like "seagulls" she was able to immediately identify that two were gulls, one was a fulmar, one was a tern, and one was an albatross. And even if I only immediately saw the tern despite doing the cards with her everyday I've noticed in my own reading that there are all these words that used to just redirect to "that's some kind of bird" in my head and now have meanings and personalities and associations with wacky behaviors captured in the photos on the Anki cards. I totally agree about the caring makes you learn and learning makes you care loop, but I always come back to the fact that caring and learning are infectious. Great Anki cards are great (and the SiW cards are for sure my kids' favorite), but in my experience kids will forgive imperfect Anki cards if they see adults caring and learning alongside them (which of course SiW also involves, and I try to facilitate in lots of other ways too).

Who says that spaced repetition has to be boring? This is the post that has finally pushed me over the edge to start building a Leitner box with my kids. Even as an avid Anki user myself, I was unconvinced that I could get my kids to engage. Between this and Brandon's homeschool workshops- no longer.

It brings a tear to my eye to think about the PEOPLE that this method will create. People with passionate interests, strong identities and lasting memories of educational experiences. It brings such a strong sense of personal history and connection to the idea of education.